Coronavirus Disease 2019

Are COVID-19 Patients at Risk for PTSD?

Recent research on post-traumatic stress and COVID-19 treatment.

Posted April 4, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

By James Fisher

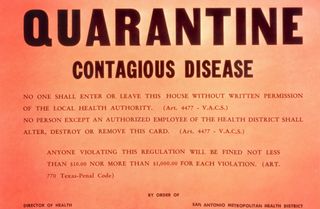

With the COVID-19 pandemic impacting so many around the world, mandatory quarantines are taking place for those who test positive for the coronavirus. Communities have come to a screeching halt in the practice of social distancing. The world is going online for remote learning and working. Sunday pews are empty, as well are parks, sporting arenas, offices, restaurants, and train stations.

Social distancing is best practice for slowing the spread, flattening the curve, and is vital for ultimately beating COVID-19. Although physical separation is necessary, there may be consequences for those isolated—especially, perhaps, coupled with the experience of having the illness—that need attention.

Researchers in China have recently investigated if PTSD was prevalent within COVID-19 survivors. The researchers were curious to investigate what the mental health status of those discharged from quarantine facilities looked like. Their research paper, published in the journal Psychological Medicine on March 27th, notes:

“According to the treatment guidelines in China, COVID-19 patients need to be treated in isolated infectious hospitals. Due to social isolation, perceived danger, uncertainty, physical discomfort, medication side effects, fear of virus transmission to others, and overwhelming negative news portrayal in mass media coverage, patients with COVID-19 may experience loneliness, anger, anxiety, depression, and insomnia, and posttraumatic stress symptoms.”

The researchers asked COVID-19 patients to participate in an online questionnaire before their release from the five quarantine facilities constructed in Wuhan, Hubei province. These temporary hospitals were specifically built to hold, quarantine, and treat people who had tested positive for the virus. The participants all needed to meet a criterion before taking part in the questionnaire. Namely, each needed to be a clinically stable adult COVID-19 patient as verified by medical records. Of the 730 patients recruited to be in the study, 714 people met standards to participate. The mean age of the participants was 50.2 years of age.

“The 17-item self-reported PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) was used to assess the severity of the posttraumatic stress symptoms. A total PCL-C score of ≥50 was considered ‘having significant posttraumatic stress symptoms.’ (X.-Y. Yang, Yang, Liu, & Yang, 2007.”

The researchers found that based on the PTSD Checklist questionnaire, the prevalence of serious PTSD in the patients discharged from the quarantine facilities was at a staggeringly high 96.2%. As stressful as being a patient may be, the researchers noted that other forces might contribute to PTSD symptoms, such as news coverage and social hostility.

The research indicates that a significant number of COVID-19 survivors suffered from PTSD before being released from quarantine. This means that COVID-19 treatment ought to not stop once the patients are released from isolation. There seems to be a need for long-term psychological interventions for survivors of the virus.

There may be implications for non-patients in social isolation. It is important to stay connected to others even when physically separated. Text messaging, phone calls, and video conferencing are all tools people can proactively use during this time. We may need to remain physically distant from one another, but we can still stay socially united.

Written by James Fisher, currently a Master of Arts Student studying Humanitarian and Disaster Leadership at Wheaton College in the suburbs of Chicago.

References

Bo, H., Li, W., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T., . . . Xiang, Y. (n.d.). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychological Medicine, 1-7. doi:10.1017/S0033291720000999