Fear

Adaptive Fears That Protect Us From Pathogens

Beware of mosquitoes, public restrooms, and hotel rooms.

Posted March 27, 2020

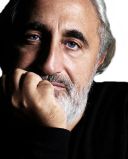

In 1977, less than two years after having immigrated to Canada from the hells of the Lebanese Civil War, my parents sent me to Camp B’nai Brith in the Laurentians (mountain range roughly one hour outside of Montreal). There, I would repeatedly encounter two of my lifelong fears: mosquitoes; and using public restrooms (a manifestation of my hyperactive disgust response at the possibility of being contaminated by another person). I am unsure that I’ve fully recovered from the horrors of that summer, which included hiding from mosquitoes (an impossible task) whilst not going to the bathroom for many contiguous days.

I am immensely repulsed by mosquitoes. The allergic reaction that one experiences when bitten by a mosquito stems from a bodily fluid exchange that takes place between us and these vectors of death. Of course, no one enjoys the prospect of being preyed upon by these vile insects, but I experience this repulsion on a completely different level. My wife and I have discussed prospective vacation destinations as a function of their “mosquito index” scores (dry weather is ideal). I will not go to sleep if I know that there is a mosquito in the house. Sleep will only take place once the bloodsucker has been squashed to oblivion. I will refrain from sitting in the garden around dusk knowing full well that I am a mosquito’s fantasy (perhaps this is not surprising since it is the female mosquito that bites; my charm transcends species).

My intense fear of mosquitoes is perfectly adaptive given that they are responsible for more human deaths and disease than all other possible predators combined (I briefly discuss this in my forthcoming book The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense). It makes a lot more evolutionary sense for you to fear a mosquito than to worry about a leopard, grizzly bear, or tiger shark. My fear is evolutionarily rational.

What about my contamination fear? It, too, is perfectly adaptive and there is no better time to appreciate this than in the current pandemic context. My disdain for being exposed to other people’s biological materials manifests itself in countless contexts. Whenever I travel, I always bring my own bedsheets. My immeasurably lovely wife goes through a decontamination process of every imaginable spot and item in the hotel room prior to my settling in. If I’m ever at a buffet, I never touch the collective utensils with my bare hands. I’m always armed with the requisite napkins. I am always happy to shake the hands of fans when they come up to me, but I always make sure to wash my hands immediately thereafter. It is no coincidence that I often resort to fist bumps rather than “moist” handshakes. Some might view my behaviors as quirky; I’d rather think that I possess a well-tuned behavioral immune system.

This brings me to a more general point rooted in Darwinian psychiatry. Many of our anxieties and fears are perfectly adaptive as long as they are modulated within a functional range. The problem arises when these sources of mental anguish lead us to dysfunction. Take, for example, OCD. As I have explained in two of my books (The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption and The Consuming Instinct) and elsewhere (see here and here), OCD is a hyperactivation of an otherwise adaptive process (see the latter sources for other relevant references). To wash one’s hands thoroughly once upon returning home makes adaptive sense; washing them for four hours prior to heading off to work is excessive.

In my next post in this series, I’ll discuss how my childhood experiences in the Lebanese Civil War might have prepared me for the current self-isolation stemming from the coronavirus pandemic.