Intelligence

Things Which Ain't So

Science is not common sense and psychology can help us understand why.

Posted May 12, 2016

“The trouble with folks is not so much their ignorance as knowing so many things which ain’t so”

—Josh Billings (1)

Let’s see how many friends I can lose today…

Quick question: Who is the more ignorant about technical matters, scientists or lay-people? (2)

Answer: Scientists. Because where lay-people might know that they are ignorant, scientists are more likely to think that they know something when actually we don’t. This means that a lot of scientists are profoundly ignorant about fields that many lay-people don’t even know exist. Worse than that—some prominent writers, both academic and popular—have called for science (or part of it) to be ended because they are openly frightened that it might overturn their beliefs. Are scientists somehow above all this irrationality by virtue of some special acquaintance with their field? Far from it—as the saying goes “you can shoot a ballistics expert”.

This, partly at least, explains such apparently bizarre modern phenomena as highly published physicists (such as Ball State Physicist Eric Hedin) who believe in creationism, and behavioural scientists who don’t believe in genetics. (3) But it’s not restricted to them.

Ok—that’s some pretty contentious remarks—so I had better qualify them somewhat before any (few remaining) scientific friends burn me at the stake. Here’s the problem:

Common-sense, and the intuitions that arise from it, is a lousy guide to the way the world actually works. If you study a field—and by study I mean devote at least five years of detailed hard daily work to it—you will spend much of that time unlearning things you previously thought to be true. You might not even realise that you have done this. But, rest assured, at the end of your 10000 hours (if that’s still a thing?) you will have spent just as much time disposing of common-sense as you have of learning new and exciting things. And, at the end of that you might have a highly non-natural mental toolkit that you can rely on--in a very narrow field.

Here's the danger--if you (as a scientist) think that this gives your gut feelings in any other field any special authority you have compounded the usual dangers of common sense with a totally unearned sense of confidence. And the common-sense alone was bad enough in the first place.

Why is this? Well, the main reason is that common-sense intuitions are part of the mental toolkit that allowed our ancestors to effectively predict a world of human sized objects at human-sized speeds, living in small groups (many of who were related) hunting and gathering as they went. Avoiding the sorts of threats that were common in that environment. Relying on the gut feelings of admired people in the group and the way we always did things before.

Common sense is made up of intuition, authority, and tradition. Trouble is, these three things are not just wrong—they are systematic barriers to understanding the way the world actually works. Because the universe isn’t largely made up of human sized things, and we have no evidence that it gives a damn about human concerns.

Science is recent, collaborative, and weird.

Science generates new knowledge about the world. Common-sense passes on old ways of surviving. That includes whatever comforting myths we happen to be hauling about to shore up our age-old intuitions that we are special magical snowflakes and not subject to the rules that the rest of the universe turned out (surprisingly) to have. Included in this set of charming (but false) notions is that we are not one critter among others, that rationality is species typical, and that we are made of some special essence.

I will take some physics examples to try to illustrate my point. And just to be clear—I am not talking about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity or wacky ol’ quantum mechanics as Krauss was above. Relativity is pretty tough to understand, all right, and no-one at all understands quantum mechanics (anyone who claims to is a liar and/or a snake oil salesman (4). Run). But--that’s not my point.

No—the oddness starts right at high school physics with the basic stuff about Newton’s laws being so wildly counter-intuitive that it takes years to teach them to someone and even when you succeed—they still get it wrong. And I know this, not because my students weren’t smart and hard working—they were. Even esteemed colleagues get these sorts of things wrong (I swear by all I hold dear that I once had a colleague teaching high school physics in the same school as me insisting that parachutes made you go upwards. He could see they did from videos…)

And it took the smartest person our species ever produced--Newton, all the millennia until only four hundred years ago to get a handle on most of it. In other words—we managed for thousands of generations without a single one of us understanding any of this stuff.

Some examples:

Intuitive Physics Example One: Ug Throw Spear

It’s intuitively obvious that the harder you throw something the longer it stays in the air. Take Ug (who has huge shoulders) and who throw the spear at the antelope. Clearly this spear has had more oomph (stop him if Ug is getting technical here) than the spear of little Uglet (who has tiny shoulders--but for the sake of this example is the same height as his dad).

Obvious but wrong. To see why have a look at the myth-busters demonstrating that a dropped bullet hits the ground at the exact same time as a fired one. The force pulling the spear (or the bullet) downwards is identical in both cases, and takes the same time.

Example Two: Ug Chase Buffalo

Ok. It’s intuitively obvious that if Ug chases a heavy thing (like a buffalo) off a cliff it falls faster than a light thing (like a rabbit) does. After all—you can just measure the splattiness (buffalo splats much more than rabbit) at the bottom (5).

Now—we went to the moon to prove this one wrong. As illustrated here:

However—think about this for a second (like Galileo did—for more than a second). We didn’t need to go to the moon to demonstrate that (correcting for air resistance) objects fall at the same rate regardless of weight.

In fact—you can do this yourself. Take a book in one hand, piece of paper in the other. Drop them both. Book hits the ground waaayy before the paper. Now put the piece of paper on top of the book (e.g. correcting for air resistance). Drop the book.

See? Now—why did it take millennia and the smartest humans to work this out?

In retrospect it’s obvious that science isn’t obvious. If it were obvious then we would have achieved success in it long ago—rather than in the last few hundred years. There are two standard explantions for this and they are both wrong.

Why is science so recent?

1) First wrong explanation: We are smarter now that our hunter gather ancestors. While its true that the Flynn effect is pulling up IQ, there are other effects pulling it down at the same time. It's likely that, in some respects, we are getting dumber. The reasons for this are complex but there is certainly no evidence that we are getting smarter, and the penalties for being dumb today (very few) are much milder than being dumb in a hunter-gatherer environment--e.g. dying.

2) Second wrong explanation: That religion stood in the way. This won’t entirely wash either. It’s true that religious authorities stood in the way of scientific advance. All authorites stand in the way of scientific advance because one of the things science does is undermine comonsense beliefs about the legitimacy of authorities... But there are highly secular figures today calling for an end to scientific endeavour—at least in certain fields. And many heroes of science were highly religious. Newton, for example, spent far more time on religion (and highly wacked-out religion at that) than he did on physics.

Ok, so, what then?

The answer, I think, lies in allowing one’s common-sense—one’s collection of gut feels--to over-ride one’s science. Science is messy, collaborative, and requires you to abandon cherished beliefs if they conflict with experiment. Most people—scientists included (in fact, sometimes they are the worst) are unwilling to do this. And even those who are capable of doing it don’t do it most of the time. Humans doing reason are like dogs walking on their hind legs—we don’t do it well and the wonder is that we do it at all.

And the only reason we can do it all is a long, constant, recorded, iterative process of winnowing out the bad ideas from the good using logic and empiricism. Reason is a collaborative enterprise not a thing that exists in one human head. It’s a group effort.

Here is one (common-sense) reason why our species finds it hard to grasp the fact that reason is a group effort—thoughts feel personal. They feel like they belong to you—that they live in a special isolated personal realm. Your inner life. Your soul.

Soul stuff

Souls are a great idea. Souls explain death (the soul has gone). Souls explain our outrageous in-group favouritism (enemies may look like us but they don’t have our magic essence—so literally dehumanizing them, is just fine). Souls also conveniently explain moral outrage via the concept of a freely choosing entity that exists separate from (mere) mechanical bodies. (6)

The notion of a soul that transcends the phsycial can go so deep that people will willingly and joyfully give up their physical lives to reach the next one. And I'm not just talking about suicide bombers here (although I am talking about them too, of course). Have a read about how happy these members of Heaven's Gate were to die--and how opposed they were to mere "suicide". http://www.heavensgate.com/misc/letter.htm

Trouble is—modern neuroscience can’t find souls and this bothers an awful lot of people.

Enter Science (stage left).

In many ways, Frederick II (1194-1250) was one of the earliest experimental psychologists. He was interested in such basic science as the existence of souls, how children acquired language, or the function of digestion. Frederick II also clearly had a fine appreciation of the importance of measurement, and the carrying out of controlled studies in advancing science.

Why Frederick II would not get a grant these days

To test the existence of souls Frederick II, had folk weighed before and after execution (7). To test whether children naturally talk Latin or Hebrew he had children raised without language by specialist deaf-mute nurses (8). Finally, he had two men disembowelled—one of whom he had run around first—to compare the effect of exercise on digestion (9).

Those pesky ethics review boards would almost certainly take issue with a modern day Frederick II. (10)

However, Frederick II did get one thing right. He was not prepared to accept supernatural explanations for anything. Trouble is—most humans are. In fact—if there’s anything species typical about humans it’s our willingness to entertain supernatural explanations for stuff.

If there's anything that distinguishes the great scientists its their awareness of the desire of the human mind to fool itself.

Feynman was a keen amateur magician and I suspect that this helped just as much as being a scientist. There were physicists who were fooled by Uri Geller--but no magicians were fooled

Benign entertainments like conjuring, not so benign exploitations like psychics, and entire cultures (11) are built upon this fact. Conspiracy theories about nefarious groups with untestable metaphysical connections between them (plotting against us) are just another form of supernaturalism. Before believing any conspiracy take a second to check if the alleged conspirators do actually share interests.

It’s not that humans don’t get together and plot against other humans. In fact—we do it all the time. But, as any glance at modern political scandals shows, we are laughably bad at it. Cover up aliens landing? We can’t even cover up tax avoidance. (12) Human plotting is usually painfully obvious and tediously self-interested. We don’t see it only when we don’t want to—i.e. because the realization that millions of humans died because none of us had the moral courage to stand up to a deluded narcissist (13) is just too painful to face.

And it doesn’t matter whether we call ourselves scientists or not. Souls keep popping up in modern forms. Whether it’s the so-called hard-problem of consciousness, complaints about so-called reductionism, or worries that “science can’t explain everything”, you can be reasonably sure that some common-sense belief lies at the root of it.

It turns out that the universe doesn’t give a toss about your fee-fees.

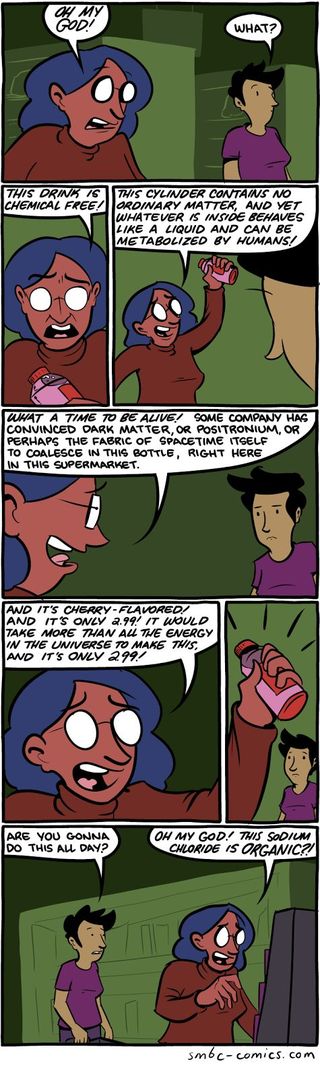

Why does this matter? Because an awful lot of common-sense is highly misleading. Well, that’s putting it kindly—it is wrong. Concepts like natural, poisonous, life forces, the accuracy of eye-witness testimony, and the existence of natural kinds are all demonstrably wrong, and pernicious pieces of common-sense. Psychology is full of examples—like confirmation bias—of the systematic ways that common-sense has to be put aside to understand the way things actually work about human minds.

So—a quick list of utterly compelling but highly misleading concepts that we find hard to shake:

A) “Natural”. Without highly detailed qualifications the term “natural” as applied so readily to foods, drugs, and behaviors is almost completely without meaning. Worse, it carries a totally bogus moral weight along with it—as if “natural” is synonymous with “good”. And don’t get me started on the word “chemical”.

Cancer is the most natural thing in the world, plumbing is highly unnatural (for any non-circular definition of the term). Connected to this is terms like “poison”. There is no such thing as a poison, or rather since everything is poisonous there is `little point in drawing attention to this fact for many purposes—as Paracelsus put it “the dose is the poison”. However, we evolved in circumstances where one berry might kill you instantly, while certain harmful behaviors might not do you in until you were well past reproductive age. Presumably this is why we can have health scares over trivia while (e.g.) smokers can manage to ignore the fact that their habit will kill about 50% of them. Horribly. (14)

B) “Seeing is believing”. Eye-witness testimony (and its social media counterpart, anecdotal evidence) is hard to shake. However, as every first year psychology undergraduate learns, it’s embarrassingly easy to manipulate people into thinking that they have seen something they haven’t seen. Even more alarming—it’s not hard to get people to confess to things they didn’t do and actually come to believe that they did it. Presumably this is because our minds evolved to produce socially and personally effective narratives, not to be de facto video recorders.

C) “Kinds”. We love categories and lines that can be drawn. Creationists are forever going on about “natural kinds”, and they are easy enough to laugh at (and deserve it too). But the rest of us want to know “where to draw the line” as well. Evolution teaches us that there are very few lines to be drawn and those that are, are often arbitrary.

D) “In-group/ out-group”. All varieties of political spectrum have a tendency to trust our own side, and (therefore) assume that the other side must be motivated by evil and/or stupidity. The other are then safely to be ignored—if not outright persecuted. Typically some sort of pseudo-scientific rationale is developed to underpin this—as if there is one thing that humans love, it’s a good story!

However, the story about how this class of people are fundamentally evil or this race of folk are fundamentally inferior are, in essence—the same story. E.g. one of dehumanization and the imputation of inhuman motives, when in fact, humans everywhere are motivated by pretty much the same sort of thing.

I can’t improve on Bertrand Russell’s summation of these motives as acquisitiveness, rivalry, vanity, and love of power. (15)

None of these things come from stupidity—on the contrary, some of the smartest of us can come up with some of the most ingenious reasons to believe daft things. But such beliefs are persistent, pervasive across cultures, and pernicious. The one crumb of comfort is that we all seem to be equal in this.

And the take home lesson is that the only way to have a chance of escaping it is to realize that, in order to reason, we need one another. Science requires collaboration. (16)

References

-

Not Mark Twain. Ironically—one of the many things which ain’t so is that Twain said this first.

-

As anyone who knows the book will realize, this whole blog owes a great deal to Lewis Wolpert’s excellent “The Unnatural Nature of Science”. Rather than reference him throughout I’ll just acknowledge that he is inspirational—which is not to say that he is in any way responsible for things I say. My mistakes are my own.

Wolpert, L. (1994). The unnatural nature of science. Harvard University Press.

-

https://whyevolutionistrue.wordpress.com/2016/05/12/id-advocate-eric-he…

-

Whatever you may have heard about noble savages living in balanced harmony with nature—the truth is that our ancestors used to chase things off cliffs and leave most of the corpses to rot. You can track human expansion with the extinction of large fauna.

Burney, D. A., & Flannery, T. F. (2005). Fifty millennia of catastrophic extinctions after human contact. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20(7), 395-401. -

By the way I realize that these two intuitions are in direct conflict with each other. Did I mention that rationality is not species typical? Eventually the cognitive dissonance works its way through-as long as we have enough of each other critically exploring each other’s beliefs for consistency. This is called progress.

-

The participants died.

-

The participants died.

-

The participants died.

-

Frederick II would probably be accused of conflicts of interest by todays Institutional Review Boards. Medieval Sourcebook: Salimbene: On Frederick II, 13th Century

-

For examples of a culture built on obviously ridiculous supernatural presumptions—use as an example any religion that you yourself don’t happen to believe in.

-

Of course—I would say this—the illuminati lizards are paying me to cover up the fact the chemtrails are being used by communists to turn vaccines gay. Or something.

-

Pick whichever one you like. There is no shortage of options. Alas.

-

Incidentally, I was one of these, lest anyone think I have some smug feeling of being above all this irrationality. I still find it hard to believe how I could have done this to myself for so many years. But there you go.

-

From Bertrand Russell’s Nobel acceptance speech, 1950.

-

And technology. Have you ever considered how imporant sand is to human reasoning? Without silicon--no computers of course. But before that we needed glass. Without glass--no microscopes or telescopes to show us that our human sized persepctive was not the be-all and end-all. And no way to carry out controlled experiments on substances freed from outside influence. Sand is really important. There is a great discussion of it here

Dartnell, L. (2014). The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Our World from Scratch. Random House.

Are we getting dumber? It's complicated. IQ is highly measurable (whatever some fashionable folk may wish fervently to the contrary) and also highly heritable. But--not all of it is hertiable. There is a well-known Flynn effect which pulls IQ up in each generation (and much faster than selection could do it)--but what is less well-known is an inverse Flynn effect that pulls some aspects of IQ down again. At the moment they appear to be pulling in opposite directions, depending on which component of IQ you are looking at. For more details read this:

Woodley, M. A., Te Nijenhuis, J., & Murphy, R. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence, 41(6), 843-850.

For some great (often counter-intuitive) experiments check out “smarter every day” on YouTube