Anger

What Are Basic Emotions?

Emotions such as fear and anger are hardwired.

Updated June 24, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Basic emotions are innate and automatic, and trigger behaviour with a high survival value.

- They evolved in response to the ecological challenges faced by our remote ancestors.

- Although they are 'hardwired', their potential objects are open to cultural conditioning.

The concept of 'basic’ or ‘primary’ emotions dates back at least to the Book of Rites, a first-century Chinese encyclopaedia that picks out seven ‘feelings of men’: joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, disliking, and liking.

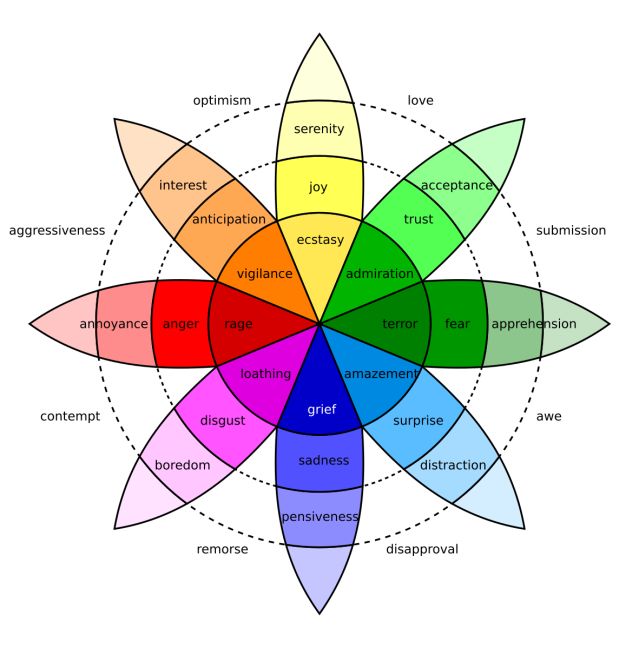

In the 20th century, Paul Ekman identified six basic emotions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise) and Robert Plutchik eight, which he had in oppositional pairs (joy-sadness, anger-fear, trust-disgust, surprise-anticipation).

Basic emotions are thought to have evolved in response to the ecological challenges faced by our remote ancestors and are so primitive as to be ‘hardwired’ into the brain, with each one operating along its own dedicated neurological circuit. Being hardwired, basic emotions (sometimes also called ‘affect programs’) are innate, automatic, and fast or reactive, and trigger behaviour with a high survival value.

One day, while holidaying on the tropical island of Mauritius, I opened a cutlery drawer on a large lizard, which, of course, I had not been expecting to find in among the knives and forks. As the critter darted off into the darkness behind the drawer, I immediately and unthinkingly jumped back and slammed the drawer shut. Having done so, I suddenly became aware of feeling hot and alert and primed for further action. This basic fear response is so primitive that even the lizard seemed to share in it, and so automatic as to be ‘cognitively impenetrable’, that is, unconscious and uncontrollable, and more akin to a reflex or reaction than to a deliberate action. As soon as reason could reassert itself, my fear disappeared, leaving me with nothing more than a mildly inconvenient lizard problem, which, I think, I chose to ignore.

One hypothesis is that basic emotions can function as building blocks, with more complex emotions being blends of basic ones. For instance, contempt might amount to a blend of anger and disgust. In 1980, Plutchik constructed a wheel-like diagram of emotions with eight basic emotions, plus eight derivative emotions each composed of two basic ones. However, many complex emotions cannot be deconstructed into more basic ones, and the theory does not explain why infants and animals do not share (or appear to share) in complex emotions.

Instead, it could be that complex emotions are an amalgam of basic emotions and cognitions, with certain combinations being sufficiently common or important to be named in language. Thus, frustration might amount to anger combined with the thought or belief that ‘nothing can be done’. But again, many complex emotions resist such analysis. What’s more, ‘basic’ emotions can themselves result from quite complex cognitions, for instance, Tom’s blind panic upon realizing, or simply believing, that he has slept through an important exam.

Although basic emotions have been compared to programmes, it does seem that their putative objects are open to cultural conditioning. If poor Tom so fears having missed his exam, this is in large part because of the value that his culture and sub-culture attach to academic success.

With more complex emotions, it is the emotion itself (rather than its object) that is culturally shaped and constructed. Schadenfreude [German, lit. ‘harm-joy’: the joy or pleasure derived from the misfortune of another] is not common to all peoples in all times.

Neither is romantic love, which seems to have emerged in tandem with the novel. In Madame Bovary, itself a novel, Gustave Flaubert tells us that Emma Bovary only found out about romantic love through "the refuse of old lending libraries."

Read more in Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions.