Bias

A Better Way to Hire

Psychometric games promise fair hiring for a polarized age.

Posted July 14, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- The "blind audition," once an ideal of equal-opportunity hiring, can lead to unequal outcomes.

- Fortune 500 firms are using "psychometric games" to screen applicants with minimal bias.

- The games used for hiring include many familiar from Psychology 101 classes.

“I just don’t think women should be in an orchestra,” said Zubin Mehta, longtime conductor of the Los Angeles and New York philharmonic orchestras. Mehta wasn’t alone in that opinion. The Berlin Philharmonic did not hire a woman until 1982, and Vienna held out until 1997. But starting in the 1970s, American orchestras made a small change in their hiring practices that made a big difference in the number of women musicians hired—from less than 5% in 1970 to 40% in 2019. The change was the “blind audition.”

A musician applying for a job performs behind a screen for a panel of orchestra members. The applicant is identified only by a number and performs an assigned piece without speaking. The panelists are not shown a résumé or told anything of the applicant’s background. They judge on the performance, the one thing that matters.

Conversations on fairness in hiring have often cited the blind audition as an ideal. Yet blind auditions have not been nearly so successful in increasing the number of African-American and Latino musicians hired. It takes a lot of money to train as a classical musician, and it’s a gamble. The musician who can’t land a job with one of the big metropolitan orchestras may have to find another line of work. That means that applicants tend to come from affluent backgrounds, leaving people of color underrepresented among classical musicians.

One reaction is: That’s OK, so long as every applicant has a fair shot in the audition. But the most prestigious orchestras are in big, liberal-leaning cities with large minority populations. Their leadership believes it’s vital to have black and brown faces in the orchestra. This has led to calls to abandon the blind audition.

As this demonstrates, fairness in hiring is a moving target. The blind audition exemplifies the colorblind equality of opportunity that most progressives supported not so long ago. But for many today, fairness means overcoming “structural” racism and sexism to achieve equality of outcomes. This is often at odds with employment law, which generally demands equality of opportunity and meritocracy (ideals that are increasingly framed as conservative positions).

Is there any way of reconciling a polarized society’s divergent views of fairness? There is an interesting attempt to leverage some Psychology 101 experiments to do just that.

Psychometric Games

If you’ve been in the job market lately, there’s a good chance you’ve encountered psychometric games. Before doing an interview or even submitting a résumé, job applicants are asked to play a series of fast-paced games on their phone or laptop. The word “game” is used to sound fun and nonthreatening. But the games are not frivolous. They are well-studied tasks and experiments discussed in the literature of psychology and behavioral economics. A battery of a dozen or so games can be completed in about a half-hour.

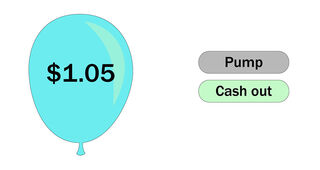

In one game, the player taps an on-screen button repeatedly to blow up a virtual balloon. The player wins play money as the balloon grows bigger. The catch is that each tap risks bursting the balloon, in which case the player loses everything. This game (known to psychologists as the balloon analog risk task or BART) measures attitudes toward risk-taking.

What does this have to do with job performance? The games are used as a sort of “personality test” to match applicants to job openings. The employer first has its most successful employees play an assortment of games. Their scores are analyzed statistically, looking for correlations between scores (high or low) in particular games and success in a specific job. This allows an algorithm to predict which applicants will succeed on the job from the game scores.

This may seem like a lot of trouble when an employer could just look through résumés for promising candidates. But there is a large body of research documenting unconscious bias among employers. A 2004 study by Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan asked: “Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal?” The researchers sent fake résumés to real employers in Boston and Chicago. They found that résumés with white-sounding names got 50% more callbacks than those with black-sounding names. In practice, those making hiring decisions tend to favor people like themselves. If relatively more employers are Gregs, and fewer are Lakishas, that puts Lakisha at a disadvantage.

Psychometric games promise to start with a blank slate. The initial candidate screening is based on games that do not come with the baggage of cultural expectations. Frida Polli, CEO of Pymetrics, one of the firms offering hiring games, told me that they found that the top salespeople at a large New York financial firm were impulsive, had short attention spans, and were willing to take risks. Those are three things you’d never see in a job description.

How someone performs on an onscreen game has no obvious connection to gender, race, age, religion, national origin, or physical disability. That doesn’t mean there isn’t one. Any statistician knows that when you look hard enough for a correlation, you generally find one.

The dozen or so games Pymetrics uses measure millions of data points bearing on 90 distinct personality traits. The games collect so much data that Pymetrics is able to provide weighted scores that are effectively bias-free across gender, ethnicity, and other protected classes, yet highly predictive of job success. In effect, they use data mining to achieve an equal-opportunity meritocracy, purged of overt, covert, and even structural bias.

That’s the pitch, anyway. Companies such as Accenture, KraftHeinz, LinkedIn, MasterCard, Tesla, and Unilever have bought it, making the games part of their hiring. Whether the marketers of psychometric games have achieved their goals is uncertain, as important parts of the data are proprietary. But if the idea lives up to the hype, it could be one of the most important developments in hiring in decades.

References

Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan (2004). “Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.” The American Economic Review 94, 991-1013.

Poundstone, William (2021). How Do Fight a Horse-Sized Duck?: Secrets to Succeeding at Interview Mind Games and Getting the Job You Want. New York: Little, Brown.