Media

A Brief History of Fake News

How spoofers and trollers learned to monetize gullibility

Posted November 22, 2016

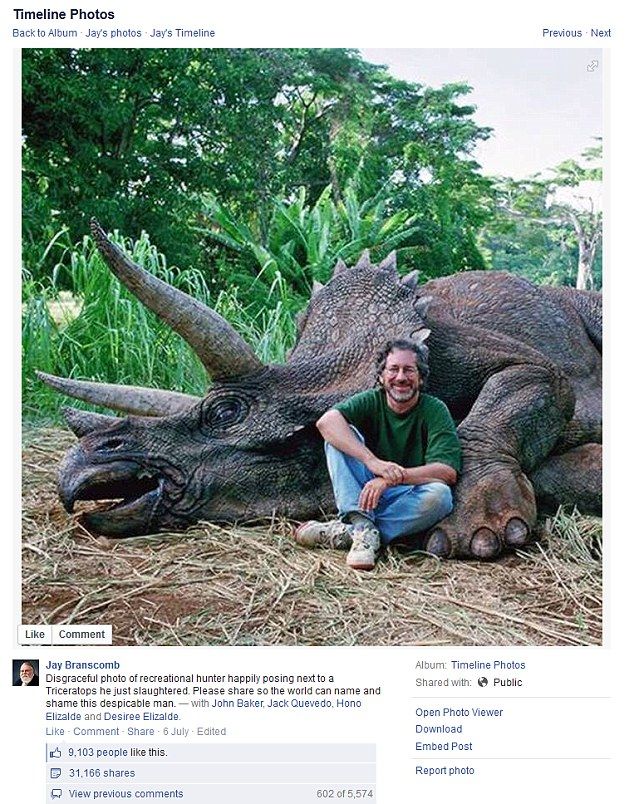

In 2015 Jay Branscomb posted a photo of Steven Spielberg sitting next to a dead triceratops on Facebook. It was a Jurassic Park publicity image. Branscomb added the caption: “Disgraceful photo of recreational hunter happily posing next to a triceratops he just slaughtered. Please share so the world can name and shame this despicable man.”

The post was shared more than thirty thousand times, racking up thousands of outraged comments. Outraged, that is, that Spielberg had shot a dinosaur. Sure, many were playing along with Branscomb’s fun, but I am confident that much of the indignation was sincere.

Lately fake news is big news. It’s been blamed for influencing a close election, and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has vowed to help get rid of it. This may not be as easy as it sounds. The problem is not just fake news but its audience. People are gullible—and not even Zuckerberg can change that.

In my book Head in the Cloud I report a survey in which 15 percent of the public believed that early humans and dinosaurs coexisted. That’s not the same as believing they’re coexisting right now, but it is an alarmingly wrong idea held by an alarmingly large share of the public.

I also found people who get their news from social networks are less informed on average than audiences for other media. I ran a survey that included a general knowledge quiz. It included items like:

• Which came first, Judaism or Christianity?

• Find South Carolina on an unlabeled U.S. map

• Name at least one of your state’s U.S. Senators

The average score for those who said they got some of their news from Facebook was 60 percent. That was 10 points less than the average scores for those listed NPR, The New York Times, or The Daily Show as news sources. Scores were even lower for Twitter (58 percent) and Tumblr (55 percent).

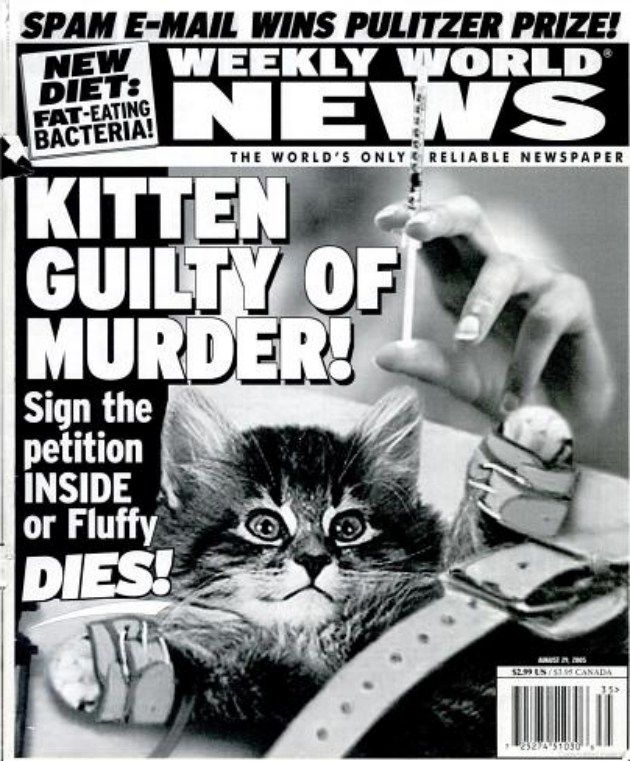

Fake news is not a new phenomenon. It has its roots in print. In 1979 The National Enquirer switched to color printing, leaving the tabloid publisher’s black-and-white presses idle. Rather than junk them, the publisher invented The Weekly World News. It had a successful, decades-long run in the check-out aisles, retailing obviously fake stories like Babies Living on Board Titanic!, Duck Hunters Shoot Angel!, and Fat Cat Owns 23 Old Ladies.

The Onion was also founded in print, in 1988, moving online in 1996. The Onion pays talented writers to produce fake news parodies that are often brilliant (“Mr. T to Pity Fool”). Despite that, clueless Facebook users have and do post Onion articles, not realizing it’s satire.

The Onion’s success spawned dozens of knock-offs, with names like The Lightly Braised Turnip, The Daily Currant, Global Associated News, Media Mass, and National Report (many of which are now defunct). Known in the trade as spoof sites, their content is largely reader-generated and not funny. They settle for deadpan conceptual prankery. Thus these sites spew steady streams of fake news that is not readily identifiable as satire. Spoof site articles regularly get posted on Facebook. Every now and then a piece gets hundreds of thousands of reposts, not because readers think it’s funny but because they think it’s true.

This election cycle saw was the democratization of fake news. Partisan fakers realized they didn’t need the spoof sites. Anyone could fake a news story or PhotoShop a photo, then post it to the social networks.

How should we deal with fake news? There has been talk of Facebook assigning a truthfulness rating to stories and using that to favor the higher-rated ones. One problem with this is how to deal with satire (which is after all one of the most popular things to post on Facebook). Surely The Onion is allowed to be The Onion, and Facebook should not keep my friends from seeing an Onion story I wanted to share.

The problem is more like trolling—facetious content that isn’t obvious as such. That may be difficult to identify by algorithm. As Branson's dinosaur prank shows, “obviously a joke” is in the eye of the beholder.

The pitch has always been that the Internet will improve the quality and relevance of news. Instead of being restricted to the narrow blinkers of a local newspaper or TV station, we can sample stories from around the nation and globe, tailored to our own interests. One drawback is that stories are effectively stripped from context—and sometimes the context matters. It does when we stumble onto someone’s deadpan joke, not realizing we’re the butt of it.

P.S. There is a site, Real or Satire?, that purports to tell whether any online news story is fake. I would say it’s useful except that the people who could most benefit from it are the ones least likely to use it.