Addiction

One Year After Charlottesville, What Have We Learned?

The need to belong helps hate groups recruit—and compassion provides a way out.

Posted August 15, 2018

One year after the violent and deadly protest in Charlottesville, Virginia, a planned anniversary demonstration of white supremacists amounted to a gathering of only a few dozen Neo-Nazis, while hundreds of anti-racists turned out to peacefully counter-protest. At a gathering on the same day in Washington, D.C., Rabbi Aaron Alexander warned that “hateful, antisemitic, racist and violent messages do have traction in this country.”1

But in a country—founded by immigrants—that is trying to live up to its ideals of equality, pluralism, and respect for differences, how do those hateful ideas get traction? Christian Picciolini understands how people can be seduced into a life of racism and violence.

Picciolini's parents were Italian immigrants who spoke little English. By working long hours, often even on weekends, they were able to move the family to a middle class neighborhood. But at school, Picciolini was bullied and socially isolated. "I felt abandoned; I felt worthless,” he recalls in the MSNBC documentary, Breaking Hate. Lonely and angry, he felt like an outsider—like he didn't belong. By the time he was fourteen, he was ripe to join any group that made him feel like he mattered.

The group that found him was Chicago Area Skinheads (CASH). Sporting boots and suspenders, a charismatic man in his mid-20s found Picciolini one day smoking a joint in an alley. He smacked the teen in the head, and pulled the joint out of his mouth. “That’s what the communists and the Jews want you to do to keep you docile,” he reprimanded. That man was Clark Martell, founder of the first U.S. neo-Nazi white power skinhead gang. Picciolini found Martell’s interest in him intoxicating, and started hanging out with his gang of violent white supremacists. He shaved his head. He emulated their style of dress. He started listening to their music. “[Martell] saw in me somebody who wanted to belong—somebody who was looking for a family,”2 Picciolini recalls. It was “a lifeline of acceptance”3 for someone who needed to belong.

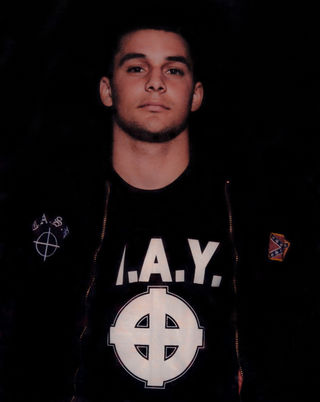

Picciolini quickly went from being a lonely teenager to being a part of something much bigger than himself. “A mouthpiece for hate,” is how he now describes himself during that time in his life. He was the front man for two American white power punk bands—White American Youth, and Final Solution. A star in the world of white supremacist music, hatred, and violence, Picciolini found people who accepted and admired him.

Two years later, Martell, who had a history of arrests and incarceration, was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He had broken into the apartment of a 21-year-old woman who left his skinhead gang, savagely beat her, and then used her blood to paint a swastika on the wall of her apartment. With Martell in prison, Picciolini became the leader of the organization. He was 16 years old.

According to the Anti-Defamation League, in 2018 alone, there have been 44 white supremacist events in the United States.4 Former white supremacists say that in an effort to cast a wider net, skinheads have made a conscious decision to grow out their hair and shift from “boots” to “suits.” Even using the “alt right” designation is part of an overall effort to recruit people who aren’t looking to join a racist movement.

While most people who hold extreme views aren’t violent, “violent extremists are a heterogeneous population of offenders whose life histories resemble members of conventional street gangs and generic criminal offenders,”5 says sociologist Pete Simi, who coauthored the book American Swastika. Gathering life histories of violent white supremacists, Simi and other researchers found that 45 percent reported being the victim of childhood physical abuse, 21 percent reported being the victim of childhood sexual abuse, 46 percent reported being neglected as a child, almost a third (31 percent) were abandoned by their parents, more than a quarter (29 percent) experienced parental incarceration, and roughly half (49 percent) reported a family history of substance abuse. More than half (59 percent) reported a family history of mental health problems, and 57 percent reported experiencing mental health problems themselves. Most of the violent extremists interviewed had a history of school truancy (58 percent), being expelled or dropping out (54 percent), substance abuse (72 percent), and early experimentation with drugs and/or alcohol before age 16 (64 percen). A staggering 62 percent reported either seriously considering or attempting suicide.6

Simi and his colleagues have likened being part of a violent extremist group to an addiction. The white supremacist lifestyle is all-consuming; it not only influences members’ thoughts and feelings, the culture involves listening to specific music, following a distinct group of alt-right commentators, and, like a religion or a cult, eating certain foods, wearing a distinctive style of dress, and participating in group events. Extremist groups create for their members a transformation of identity through a totalizing experience of acceptance and belonging. Through group rituals such as marching and dancing, they even provide members with a transcendent experience of shared emotion known to social scientists as “collective effervescence.” Before becoming violent extremists, many members had experienced a painful failure to belong. But as members of one of these groups, they experience a powerful sense of purpose and belonging. It’s no wonder that it can be difficult to disengage. Being a part of these groups is extraordinarily compelling even for members who don’t fully subscribe to the violence or racism. And leaving them can be dangerous—as Martell's victim found.

Another challenge for those who want to leave is to expand who counts to them as “us.” Racist, antisemitic, and anti-gay sentiment is characterized by a rigid and narrow definition of “us” and the unambiguous dehumanization of “them.” This “otherizing” is accomplished not just cognitively (by consciously rejecting inclusive American ideals of pluralism and diversity) but emotionally, through a toxic combination of anger, contempt, and disgust. This is tribalism at its most dangerous—and deadly, as we learned from Charlottesville in 2017. For members of extremist groups, it becomes a powerful worldview that can be difficult to shake.

In high school, Picciolini, by then a violent skinhead, got into fights and was frequently suspended and expelled—once being led out of a school in handcuffs. By the time he was 21, he had two children, a failing marriage, and a music store that sold white power music. His store sold other kinds of music, too, though, and for his business to survive, he had to interact with all kinds of customers—including some who were black, some who were Jewish, and some who were gay. His customers knew about his skinhead affiliation, he says, and yet they still treated him with dignity. “These people that I thought I hated took it upon themselves to see something inside of me that I didn't even see myself, and it was because of that connection that I was able to humanize them.”7 That, he says, is what broke the spell of racist ideology and hatred. Through the kindness of people he had thought were “them,” he was able to develop an expanded sense of “us.”

As I’ve written elsewhere:

The fundamental mistake we make is using tribal rather than civic norms in defining who counts as “us.” It is not that other people must be or think more like “us” to be less of a “them.” Instead, the more we expand our understanding of who counts as “us,” the less like “them” those other people appear.

As counterintuitive as it seems, it is a mistake to use tribal norms even regarding how we think about people who hold racist ideas, and even regarding how we think about violent extremists. As logical as it seems to shun and demonize those who engage in bigotry and violence, the language we use to “call out” racism is the same demeaning, dismissive, and dehumanizing language that racists use against their victims. We think racists are disgusting and deserve our contempt. They should crawl back under their rocks. They aren’t really human. They’re rodents. They’re vermin. They’re monsters. We indulge in the same toxic emotional brew of anger, contempt, and disgust regarding racists that white supremacists feel about their out-groups. Yet, what saved Picciolini was interacting with people who had compassion toward him—people he had thought were his enemies.

If the only people who will talk to racists are other racists, no minds will ever be changed. When the only people who see them as human are white supremacists, and the only places they are allowed to belong are in violent extremist groups, those groups become more powerful. Picciolini knows this not only because being accepted by a diverse group of people who didn’t subscribe to his racist ideology transformed his life, but also because he has transformed others' lives by helping more than a hundred people leave extremist groups. “Dialogue can lead to understanding and acceptance,” he says. And that’s “the opposite of what the white supremacists are pushing.”

In order to disengage from racist groups—and make amends—extremists must interact with people who are not part of racist groups and who treat them with dignity and compassion. We dehumanize those who dehumanize others at our own peril. “If you purely stigmatize people and don’t offer them opportunities for redemption and reintegration, then you create a self-fulfilling prophecy,” says Simi. “You prevent the possibility that the person might leave or change because you’ve given them no opportunity.”8

As chronicled in the Breaking Hate, Picciolini brought a young man named Gabe, an ambivalent white supremacist who marched in Charlottesville, to meet Susan Bro, the mother of murdered counter-protester Heather Heyer. Gabe had learned to think of Heather as one of "them"—a "communist" who wanted to destroy America. But as the pair sat together and talked about those false narratives regarding Charlottesville that circulate through white supremacist groups, including about the cause of Heather Heyer's death, Gabe learned he had been deceived. He and Susan even uncovered similarities in the challenges Gabe and Heather faced in childhood. As they said goodbye, the mother of the murdered peaceful counter-protester and the soon-to-be ex-white supremacist embraced.

“Have real conversations with people around you,”9 Susan Bro implored on the anniversary of her daughter’s death. “That is where big change is going to happen.” ♦

Pamela Paresky's opinions are her own and should not be considered official positions of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) or any other organization with which she is associated.

References

For more about Christian Picciolini, see Picciolini, C. (2015). Redemption Song. Intelligence Report. Southern Poverty Law Center

2. Breaking Hate. MSNBC documentary. (All Picciolini quotes without citations were transcribed from the documentary.)