Education

Why 9 out of 10 Parents Think Their Kids Are at Grade Level

A news article claims this is a mathematical impossibility.

Posted April 22, 2016

In a recent article, NPR's lead education blogger, Anya Kamenetz reported some sobering statistics on the state of public K-12 education. Citing the results of an undisclosed survey on public education, she noted that 90 percent of parents stated that their children were performing at or above grade level in both math and reading. But according to the nationally administered test known as the Nation's Report Card, only about half of white students are on grade level in math and reading by fourth grade; the percentages are lower for African-Americans and Hispanics.

Kamenetz points out that believing "all the children are above average" constitutes a mathematical absurdity; yet, according to her interpretation of the data, almost all parents believe this absurdity to be true.

Predictably, the education experts quoted by Kamenetz pointed the finger at parents, who, they argue, are not involved in their children's education, and who have at best a tenuous understanding of the concept of "average" themselves.

Bibb Hubbard, founder of Learning Heroes, an organization whose mission is to provide resources that enable parents to teach their children English language arts and math, calls this result shocking. "There is this cognitive dissonance happening," Hubbard says. "We've got to find good, productive ways to educate and inform parents."

Predictably, most readers who commented on the article jumped either on the "blame the parents" bandwagon or "blame the schools" bandwagon.

According to readers who point the finger at poor parenting:

"Parents who are not involved at all in their child's education, are a huge problem. Parents who challenge and second guess every determination the teacher makes, are a huge problem."

"Neither one of these was an issue when I was growing up in the 70's."

"This just shows that parents are simply not involved with their kids and/or the education of their kids."

According to those who believe schools are at fault:

"we need to reintroduce severe gender discrimination and force higher quality people back into teaching"

"In a world where every child gets a trophy just for showing up and A's are handed out like popcorn, this should be no surprise."

And according to this reader, the results simply demonstrate foolish human pride:

"26 people in a room. 25 blindfolded subjects. 1 proctor.

Proctor: If you believe you are above average in ____, raise your hand.

20 hands go up.

Humans..."

But before jumping on any of these bandwagons, consider this:

Kamenetz has seriously misunderstood or misrepresented what "performing at grade level" means.

Kamenetz seems to believe "grade level" means "average", so it indeed would be absurd for almost all parents to believe their children are performing at or above average. But that isn't what "grade level" means.

A grade level standard is a minimum that all children are expected to achieve, not an average. It is typically defined as what all students should know and be able to do at each grade level, and this varies from state to state. So, if almost all parents believe their children have achieved grade level competency, this is not proof that they are reasoning fallaciously. It is not only a mathematical possibility for all children to reach grade level competency, it is a goal the education system explicitly seeks to achieve.

Now let's consider the fact that parents believe their children are achieving grade level competency when the data show that half of them aren't achieving those goals. If half of children are not performing at grade level, that means that either teachers aren't doing their jobs or that what is considered "grade level" competency is unrealistic. It is not evidence that Americans are bad parents. In fact, as pointed out in the article, the high school graduation rate is over 80 percent, and fewer than 2 percent of students are held back a grade, so parents can hardly be faulted for believing their kids are doing OK in school.

According to one reader,

NAEP reports scores at four achievement levels -- Advanced, Proficient, Basic, and Below Basic. They do not report "grade level," which is impossible to do in a nation that does not have a national curriculum. The reporter seems to be confused about the meaning of "Proficient," which is surely not meant to be "grade level". (Some knowledgeable people say it means roughly A or A minus work.) It might be better to worry about those students in the bottom achievement level. For example, in the 2015 NAEP mathematics exam at 4th grade, 18% were Below Basic. In 1990, 50% were.

(Note: I fact-checked this, and it is accurate. You can take a look for yourself here.)

It is also important to remember that children today are expected to learn material at much younger ages than their parents or grandparents were expected to do. In the 1950's,1960's, and 1970's, reading was introduced in first grade, and algebra was not introduced until freshman year of high school and ONLY for students who were in the college prep track. Today, preschoolers are expected to know how to read because their parents are expected to have already taught them, and algebra is introduced to all children in grade 6.

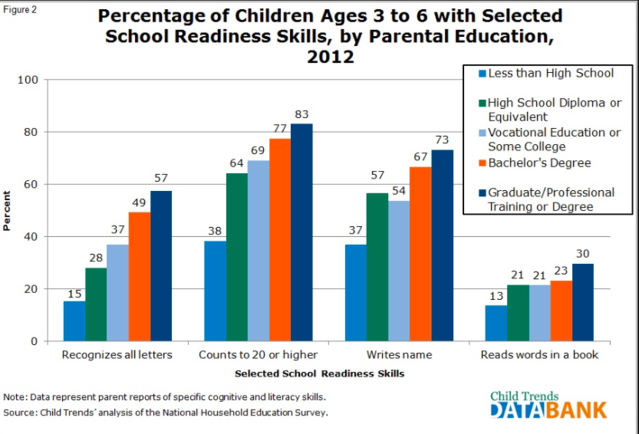

There is no scientific evidence showing that the majority of children are prepared to learn these things at earlier ages. When the majority of children fail to achieve unrealistic standards, experts tend hand the problem back to the parents. Consider, for example, this graph from Child Trends, a nonprofit research organization focused exclusively on improving the lives and prospects of children, youth, and their families. The graph shows the skills that children between the ages of 3 and 6 are expected to have in order to be considered "ready for school". Notice that even among children of the most educated parents, only about 30% can read words in a book.

My own experience as a parent brought me to understand that teachers often alternate between railing against "helicopter parents" who are "overly involved in their children's lives" and claiming that "parents these days are just not involved enough in their kids' lives."

For example, my daughter (an otherwise A student) had difficulty with some of the math she was supposed to learn in middle school. Her teacher sent home a note telling me to "spend more time helping your daughter learn". I called the teacher and told her that I was spending an hour every evening and more on weekends going over the material with her, which she just found very difficult. Without skipping a beat, the teacher replied, "Well, that's the problem. You're spending too much time with her and now she doesn't like math."

It did not escape my notice at the time (nor does it now) that college professors are required to hold office hours weekly so that students who are having difficulty with the material can receive extra assistance. But when I suggested to the school principal that her teachers set aside 1-2 hours weekly to meet with struggling students, she responded quite vehemently that teachers were already too busy, and it was the parent's or a tutor's job to help children who were struggling with the material presented in class.

In that moment, something clicked in my mind: I understood why so many students entered college not only unprepared for college work, but were resigned to the idea that it was "normal" to not understand what was going on in class.

There is indeed a good deal to concern us about K-12 education. But the "facts" presented in the NPR article point more to our holding children to unrealistic standards than to their parents failure to understand math or involve themselves adequately in their children's lives.

Copyright Dr. Denise Cummins April 22, 2016

Dr. Cummins is a research psychologist, a Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science, and the author of Good Thinking: Seven Powerful Ideas That Influence the Way We Think.

More information about me can be found on my homepage.

My books can be found here.

Follow me on Twitter.

And on Google+.

And on LinkedIn.