Psychiatry

Remembering David J. Impastato, M.D., Pioneer in ECT

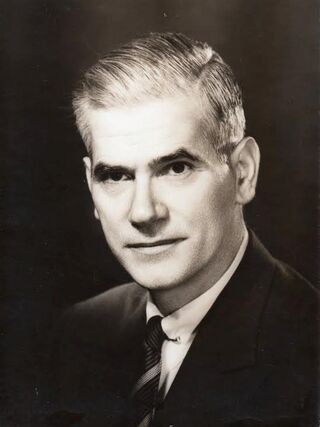

The first psychiatrist to administer ECT in North America.

Posted August 22, 2020

"I am not for any one type of treatment. I am only for the patient." – David J. Impastato, M.D.

At the turn of the twentieth century, few acceptable treatments for severe mental disorder existed apart from the "talking cure" of psychoanalysis, which Freud himself deemed unsatisfactory, at least in its original form, for the most severe cases of psychiatric disease. Simple confinement and custodial care were the only real options for these patients, which, with continued waves of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, led to a quickly expanding state hospital system in the United States.

Among those European immigrants was a young family from Mazara del Vallo, Sicily—a mother, Rosaria; her 9-year-old son, Davide; and several other children—settling in New York City's thriving Little Italy section. Rosaria's husband Domenico, a schoolteacher, stayed behind in Sicily and died before he was able to rejoin his wife and family in America. From an early age, Davide was recognized for his exceptional intelligence and academic performance, prompting Rosaria to start a college fund for her son comprised mainly of monies earned by Davide's older siblings in New York's garment district.

This young Sicilian boy, David John Impastato, would go on to Columbia University and then the George Washington University School of Medicine, becoming one of America's finest and most well-respected physicians. He gained international recognition as a pioneer in the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), one of the first real treatments for severe mental disease.

While the Germans, the Austrians, the French, and the Brits all made their own contributions to psychoanalysis and psychiatric nosology, Italian psychiatry's claim to fame is its development and refinement of ECT. The Venetian-born neurologist Ugo Cerletti and his colleague Lucio Bini, a psychiatrist at the University of Rome, discovered the therapeutic effects of electrical current in 1937, later being nominated for a Nobel Prize in Medicine for their discovery.

In 1939, the Italian psychiatrist Renato Almansi immigrated to the United States to escape rising political tensions and brought with him one of Cerletti and Bini's early ECT machines. After being introduced to the Italian American Impastato, whose work had caught the eye of one of Almansi's former professors in Rome, the two began early experiments with the Cerletti-Bini device in the hope of introducing the procedure to American psychiatry.

On January 7, 1940, at his private office and residence at 27 W. 55th Street in Midtown Manhattan, Impastato administered the first ECT treatment in North America to a 29-year-old woman with schizophrenia (Lebensohn, 1999). Almansi was not present for the procedure since it was arranged spontaneously following the unscheduled visit of the patient's father, who desperately pleaded for anything that might help his sick and rapidly deteriorating daughter. As Almansi recounted years later, this sense of human urgency played a large part in the precipitous nature of the landmark procedure. Impastato's wife Jane, a registered nurse, assisted with the treatment.

Soon thereafter, Impastato sought a hospital to sponsor his ECT work, but the medical establishment in the United States was averse to the controversy surrounding the treatment. He appealed to New York's Columbus Hospital (later named Italian Hospital and Cabrini Medical Center), where he had served in the psychiatry department for a half-dozen years, which agreed to sponsor an ECT clinical trial. Impastato and Almansi began their work there on February 6, 1940, the earliest hospital-based ECT treatment on record in North America (Lebensohn, 1999).

In September 1940, Impastato and Almansi reported their findings in a paper titled "Electrically-Induced Convulsions in the Treatment of Mental Illness," published in the New York State Journal of Medicine—the first ECT research study to appear in a U.S. publication. During the war years in the early 1940s, ECT was adopted by virtually every major psychiatric institution in America and revolutionized care for the most severely ill. For the first time in history, a safe and effective biological treatment for mental illness could be offered. Other American pioneers in ECT, such as Lothar Kalinowsky and Douglas Goldman, conducted their own research on the novel treatment.

Impastato's work on ECT would continue to evolve in the following decades, earning him international recognition and acclaim. His private practice expanded into large offices on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue, where he treated patients ranging from New York's millionaire class to the city's poor and disenfranchised—a testament to his immigrant roots. He described his clinical approach as "eclectic" (American Psychiatric Association, 1977, p. 619), offering not only biological treatment but also psychotherapy, stating that there is a "psychic component in any treatment situation, even if the therapy seems to be essentially somatic" (Impastato, 1955, p. 528).

In the 1950s, Impastato made a major breakthrough when he discovered that succinylcholine, a muscle relaxant, preserved the efficacy of ECT while eliminating the convulsive force in the patient. This drug is still used in ECT procedures today. As pharmacological therapies for mental illness became more widespread in the 1960s, Impastato advocated for ECT as a treatment for cases resistant to medication and psychotherapy, insisting that all three modalities are important components of the psychiatrist's toolbox. He also published extensively on the misuse of ECT—a problem observed mainly at the overcrowded U.S. state hospitals—and the complications often arising from its improper administration.

Impastato remained married to his wife Jane until his death in 1986 at the age of 83 from complications of Parkinson's disease. The couple had three children and five grandchildren. In the words of a former colleague, Impastato's "genteel personality and manner" (Reiter, 2013) endeared him to friends, co-workers, and patients.

Today, an estimated 100,000 U.S. patients receive electroconvulsive therapy annually (Hermann, Dorwart, Hoover, & Brady, 1995). The treatment has saved the lives of thousands of patients since its discovery in 1937.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1977). Biographical directory of the fellows and members of the American Psychiatric Association. Bowker.

David J. Impastato obituary. (1986, March 11). The New York Times. p. 31.

Hermann, R., Dorwart, R., Hoover, C., & Brody, J. (1995). Variation in ECT use in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(6), 869-875.

Impastato, D. J., & Almansi, R. (1940). Electrically induced convulsions in the treatment of mental illness. New York State Journal of Medicine, 98, 1315-1316.

Impastato, D. J. (1955). Physiologic therapy in psychiatry. Journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey, 52, 528.

Lebensohn, Z. M. (1999). The history of electroconvulsive therapy in the United States and its place in American psychiatry: A personal memoir. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40(3), 173-181.

Reiter, J. M. (2013, December). Personal correspondence. The Osar Diethel Library, DeWitt Wallace Institute for the History of Psychiatry. Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

Shorter, E., & Healy, D. (2017). Shock therapy: A history of electroconvulsive treatment of mental illness. Rutgers University Press.