Education

A Hundred Years of Children’s Freedom

Summerhill School celebrates its centennial.

Posted June 29, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

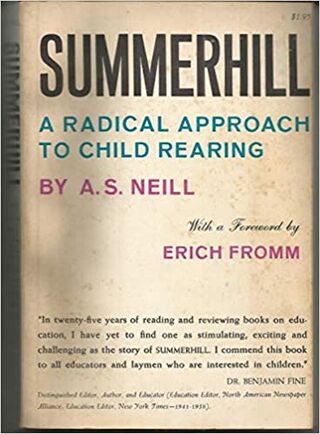

Have you heard of Summerhill School? In the 1960s and early ‘70s, most Americans involved with education would likely have said yes. In 1960, a book called Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing was published for a North American readership. The book was a collection of some of the writings of Alexander Sutherland Neill, who in 1921 had founded a radically alternative boarding school that eventually found a permanent home in Leiston, Suffolk, England, and came to be called Summerhill. The book came with a strongly favorable foreword by the well-known psychoanalyst and social critic Erich Fromm, and it quickly became a best seller. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the 1960s, and by 1970 it reportedly was assigned reading in approximately 600 university courses (Miller, 2002).

I remember thinking, when I first read the book and became involved in discussions about it, shortly after graduating from high school (in 1962), “The days of schooling in the foolish way we are doing it now are numbered; now we know the alternative.”

I’m still thinking that.

Summerhill is and has always been a certified school, because school is where children by law are required to be. But Neill was really not much interested in academic education. He was interested in children—real, whole children—and their development. Although academic courses have always been offered at Summerhill, students take them only by choice; none are required. Neill was much more interested in children’s happiness and social and emotional development than in their academic accomplishments. He recognized that children learn far more through their own natural explorations, play, conversations, and real-world experiences than they do sitting in classrooms. He also recognized that when people are happy and motivated, they can learn academic material any time they wish or need to.

The Historic and Contemporary Importance of Summerhill

Many if not most of the schools in the world today that call themselves “democratic schools” or in other ways focus on the preservation of children’s rights and the value of freedom owe at least some of their philosophical origins to A.S. Neill and Summerhill.

In the United States, Neill’s book almost immediately inspired the formation of the Summerhill Society, which published a Bulletin to disseminate ideas and information supportive of freedom in education. New, little private schools, referred to generally as free schools, began to sprout up throughout the United States. It is hard to know just how many there were, but one source—the New Schools Exchange Directory—listed 320 operating in 1971 (Houseman, 1998). Most of the schools were founded by idealists who were not particularly savvy about business and organizational planning, and most eventually failed—partly because of inability to pay staff, partly because of failure to work out systematic ways of resolving disagreements among those involved with the school, and partly because the wave of idealism (commonly referred to as the Movement), which drew the passions of many young people in the 1960s began to fade in the 1970s (Hausman, 1998).

For me personally, the primary historic connection with Summerhill is through the Sudbury Valley School, in Framingham, Massachusetts. That’s where my son went to school and where I began my own research into play, child development, and education. Sudbury Valley was one of those little schools founded in the 1960s, inspired by Summerhill, but unlike so many of the others it was carefully planned and did not tie itself to any political ideology or movement. It has always, like Summerhill, considered itself to be a free marketplace of ideas, with no institutional political agenda other than freedom and respect for children and for the democratic process. I have written elsewhere about Sudbury Valley (e.g. here) and its primary founder Daniel Greenberg. Here it is sufficient to say that Sudbury Valley celebrated its 50th anniversary of continuous operation four years ago and has itself inspired the origin of many new democratic schools throughout the world; in some sense the grandchildren of Summerhill.

Summerhill continues today as a thriving boarding school that also accepts a few day students, with a student body of roughly 75, age 5 to 17. The headmistress is A.S. Neill’s daughter Zoë Readhead. Over the years, the school has sometimes been threatened with closure by the British Department of Education because it violates the law stating that classes must be compulsory, but it has survived all such challenges. In a celebrated case, tried in 2000, the school was dramatically successful in court with the help of Summerhill students, who staged a "school meeting" in the courtroom (see here and here). The case apparently led to reform in how the Department evaluates schools.

A Summerhill Mantra: Freedom—Not License

After the U.S. publication of Summerhill, Neill apparently got word (accurately or not) that the “freedom” he advocated had been misunderstood or misapplied by some of the “free schools” in the United States to justify students’ unruly and disruptive behavior. As a corrective, Neill authored a new book, entitled Freedom—Not License! Here he made it clear that freedom concerns the rights of the individual, but everyone has rights, so the concept of freedom does not justify behavior that interferes with the rights of others.

Summerhill has rules, which are enforced, as do most schools today that are inspired directly or indirectly by Summerhill. The rules are made democratically by all who are affected by them, and “freedom not license” is the guiding principle behind them. Neither Summerhill nor Sudbury Valley refers to itself as a “free school,” because that term suggests anarchy. Both prefer the term “democratic school,” making it clear that there are rules, democratically made. [I know that some of my friends and readers can mount a strong argument for anarchy, and say it is not inconsistent with order, but that discussion can wait for another time.]

Zoë Readhead returned to the freedom-not-license theme in a 2021 book entitled Barefoot in November: Parenting the Summerhill Way, which I recommend to all parents. In simple, common-sense language, she describes how the basic practices of freedom and respect for one another that make Summerhill work, including establishment of rules or boundaries, can be applied, though somewhat differently, in families. I see the book as a set of recipes for returning joy and freedom to parents as well as children.

The Summerhill Festival of Childhood

Summerhill is celebrating its centennial on August 5-10, 2022, with a Festival of Childhood, which will be held on grounds very close to the school, in Leiston. (The school is actually now 101 years old, but it delayed the celebration a year because of COVID.) People interested in democratic education and children’s freedom and happiness will be coming from all over the world. Perhaps you will join.

I close now with one of my favorite Neill quotations: “The function of the child is to live his own life—not the life that his anxious parents think he should live, nor a life according to the purpose of the educator who thinks he knows what is best.”

And now, what do you think about this? … This blog is, in part, a forum for discussion. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Psychology Today no longer accepts comments on this site, but you can comment by going to my Facebook profile, where you will see a link to this post. If you don't see this post near the top of my timeline, just put the title of the post into the search option (click on the three-dot icon at the top of the timeline and then on the search icon that appears in the menu) and it will come up. By following me on Facebook you can comment on all of my posts and see others' comments. The discussion is often very interesting.

References

Hausman, T. (1998) A history of the free school movement. Available online at http://www.tatehausman.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/freeschools-hausm…

Miller, R. (2002). Free schools, free people: Education and democracy after the 1960s. Albany: State University of NY Press.