Deception

Research Shows What Questions to Ask to Get Honest Answers

A recent review of research on deception.

Posted December 11, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The purpose of asking questions, generally speaking, is to obtain accurate information to, say, improve one’s understanding or performance.

- But the type of questions posed may affect the answer provided—for instance, by signaling the asker’s knowledge or desired response.

- By becoming aware of the signals our questions convey, we can increase the likelihood of receiving truthful answers.

Published in the October issue of Current Opinion in Psychology, an article by VanEpps and Hart discusses the latest research on deception and on how to ask good questions (or better questions) to get at the truth.

Why do we ask questions? Generally, to increase knowledge, improve understanding, and obtain truthful and helpful information. However, respondents—whether a job applicant, friend, classmate, romantic partner, or one’s child—may not provide an honest answer. Alternatively, they may dodge the question or choose not to answer at all.

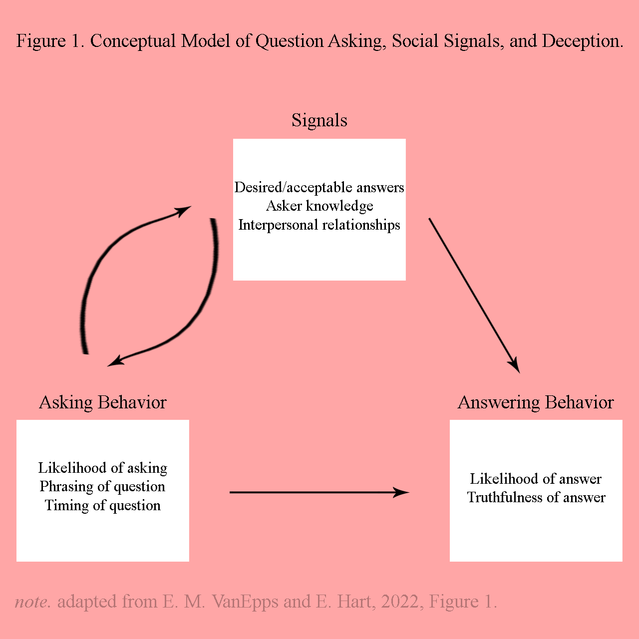

As discussed below—see Figure 1 for a visual summary—in order to elicit truthful answers, one must be strategic. This means obtaining as much information as possible before and during the interaction, and then pose the right question at the right time and in the right way.

The respondent may lie and give answers the asker expects or desires

The first thing is to understand that a question is not merely a question but also a signal:

When or how a question is posed could unintentionally reveal what the questioner desires to or expects to hear.

Therefore, it is better to ask, “How did you feel?” than “How angry were you?” Or, “What kind of pain, if any, are you feeling at the moment?” than “You are not in any pain now, right?”

It is also important to remember that asking lots of questions in a short time may signal that you prefer briefer and less detailed answers.

You may not receive accurate answers either by asking yes-no questions—particularly regarding uncommon issues or undesirable behaviors. In such cases, it is important to normalize the issue you are inquiring about.

To illustrate, instead of asking your adolescent, “Have you ever used an illegal drug?,” ask a series of questions about using different drugs, including both legal and illegal ones. This latter approach suggests illicit drug use is common, so it makes it easier for your child to be truthful.

What the questioner knows

Because asking the wrong questions may communicate the asker’s lack of knowledge, intelligence, or competence, it is important to prepare. This often requires obtaining information from multiple sources (e.g., books, Internet, friends) before speaking to the target.

Posing questions that (rightly) presuppose a problem and asking how significant the issue is, suggest more competence than questions that make no such assumptions. To illustrate, asking the hiring manager, “How often do I need to deal with angry customers who are tired of waiting?” shows more knowledge than “Will I need to deal with angry customers?”

Asking questions that accurately presuppose a problem will convince the respondent that you are well-informed, which will motivate him or her to be more truthful.

Concerns regarding damaging the relationship

When we ask questions, we do not always seek information only; sometimes we also want to make a good impression or establish or enhance our relationship. But it can be difficult to achieve both the informational and interpersonal goals at the same time.

Indeed, sometimes it may be necessary to ask unexpected and sensitive questions, despite them making the respondent (or both parties) uncomfortable. The reason for this is that liars usually prepare answers for typical questions they could be asked. So asking unexpected questions may be necessary. Yet, doing so may damage rapport by suggesting the questioner’s lack of trust.

Additionally, the questions might come across as intrusive, particularly if previous interactions between the parties have been limited to small talk. Therefore, they are rightly avoided when the relationship is highly valued.

Then again, there is often too much focus on the potential harm and relational costs of unanticipated questions. This ignores not only the importance of informational goals but also how asking questions can express interest and concern, thus potentially strengthening the relationship.

To illustrate, a supervisor’s regular inquiries about work updates may signal not criticism or distrust but interest in the employees’ progress toward their goals.

Concerns regarding reciprocation

By asking questions, one signals interest in a topic, so it is not surprising to receive similar questions from the respondent. For instance, asking about your coworker’s love life or salary may prompt him or her to ask about yours.

The obvious way of preventing this is to not ask questions we cannot or do not want to answer ourselves. However, this allows the persistence of misperceptions, misinterpretations, and lies of omission—that is, deception through leaving out important information, as opposed to lies of commission, which means generating false information.

Takeaway

Here are some suggestions on how to get honest answers.

One, when exploring rare or undesirable behaviors, remain neutral or normalize the behavior. For instance, ask about a sensitive matter in the midst of asking expected or typical questions. Alternatively, pose an indirect question, inquiring about similar others (e.g., “How much porn do you think single guys your age watch?”).

Two, to reduce the probability of lies of omission, learn as much as possible about the topic, and then ask questions that signal your knowledge and competence.

Three, before asking questions, reflect on your informational or relational goals. Just as your relationship with the respondent affects the kinds of questions you feel comfortable asking, posing certain types of questions can affect the relationship’s future.

Hence, if you value the relationship highly, formulate the questions in a way that signal curiosity and interest, not suspicion and mistrust. Respondents who feel they will not be believed or respected are more likely to engage in deception, thinking there is no point in trying to be truthful.

Having said that, do not avoid asking relevant questions for fear of damaging the relationship. Asking the right questions, even sensitive ones, can show interest and care, improve liking, and enhance the relationship.