Law and Crime

Are Immigrants Dangerous?

Why do we assume that minorities or immigrants are criminals?

Posted November 3, 2018

Linking immigrants and crime

A new Trump campaign ad links illegal immigration and crime. It features an undocumented and twice-deported Mexican immigrant convicted of killing two American police officers. In the clip from his trial, the convict is grinning as he says, “I'm going to kill more cops soon.” To some people, this clip is further proof that ethnic minorities, migrants, especially undocumented immigrants, are more likely to commit serious crimes. In today’s post, I discuss one reason for this mistaken conclusion: Illusory correlations.

An illusory correlation is a cognitive bias which occurs when an observer assumes two unrelated events are related or assumes a stronger association between two events than is actually the case.

In this post, I begin with a detailed example to show how an illusory correlation forms, then examine the consequences of these mistaken associations, and finally, speculate on how to avoid them.

Criminals among us

It is very easy to form illusory correlations. Let me use a detailed example to illustrate.

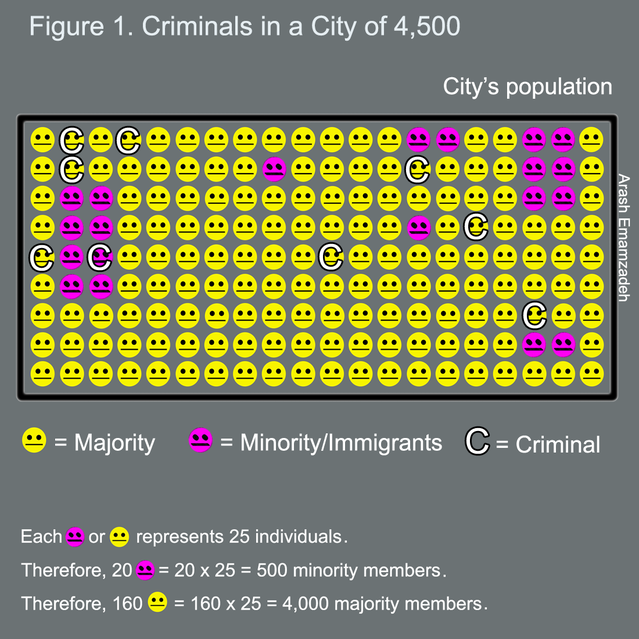

I would like you to imagine living in a small city of 4,500. You are one of 4,000 people who comprise the majority. The other 500 are undocumented immigrants. Or ethnic minorities, racial minorities, sexual minorities—or another label of your choice. Just remember that your group is much larger than the other, and thus you are not likely to interact with members of this smaller group regularly.

Suppose 5% of each group are dangerous criminals: 200 individuals (out of 4,000 majority members) and 25 individuals (out of 500 minority members).

As you can see in Figure 1, majority criminals (yellow faces with the letter C) outnumber minority criminals (the one purple face with the letter C). So why would someone conclude that crimes are more likely to be committed by ethnic minorities or undocumented immigrants than by the much larger majority?

Formation of illusory correlations

Suppose one morning on your way to work, you witness an ethnic minority student stab an old man. A month later, you read about an illegal migrant murdering a young couple. Two months later, you watch a televised trial of an immigrant convicted of the attempted murder of his own family.

By now, you might have formed an illusory correlation between terrible crimes and being a racial minority or immigrant. For instance, you feel anxious whenever you come across members of this group. When one gives you an angry look, when one uses a curse word on the phone, and even when you see two of them standing around smoking cigarettes, a voice in your mind whispers: Murderers! Murderers!

But you formed this association based on only three people committing serious crimes. So how did it happen?

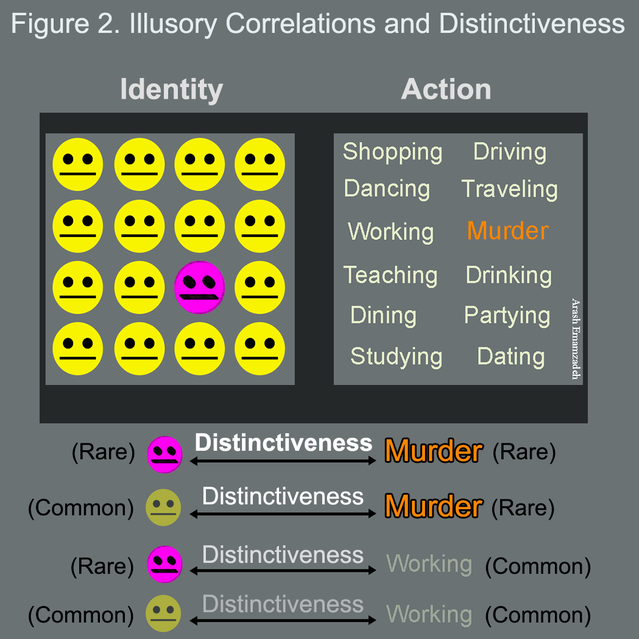

One explanation emphasizes distinctiveness.1 According to this view, illusory correlations are perceived between events and characteristics that are distinct—extreme, unusual, or rare.

The formation of illusory correlations is facilitated because both the individual (an immigrant) and the act (of murder) are distinct. Had a person belonging to your group (i.e. the majority) committed the same terrible crime, the crime would be distinct but the individual’s identity would not be. Even less distinct is someone from your group doing something unremarkable, positive, or common (e.g., being interviewed about working overtime). See Figure 2.

Consequences of illusory correlations

In the above examples, based on only three people committing serious crimes, you concluded that many of the 500 immigrants in your city are dangerous—when in reality only 25 are. In comparison, the majority includes 200 dangerous individuals. Thus, because you have formed an illusory correlation, you now assume that a group eight times smaller than yours poses a bigger threat!

If many members of your group, as a result of exposure to news, have also formed an illusory correlation between illegal immigrants and crime, they read murderous intent into words and actions of minority members.

Treating minorities as potential criminals elicits hostile reactions from them too; these reactions only further “prove” that immigrants or minorities are dangerous. This dynamic can result in a vicious cycle, giving rise to paranoia, hostility, and aggression on both sides.

How to avoid illusory correlations?

Immigration is not associated with increased crime. In addition, although research on undocumented immigrants is limited, available data do not indicate that deportable aliens pose a unique threat.2

Of course, merely being told that immigrants or people of a certain ethnicity (or nationality, religion, etc) are not dangerous is not sufficient. Learning needs to occur on a deep experiential level. It requires people of different backgrounds to eat together, work together, and play together. To share histories, values, hopes, and dreams.

The goal is to give ourselves a chance to learn that immigrants or ethnic minorities, like everyone else, are neither evil nor perfect; they are human. Having learned that, if we then see a video of a murderer on TV who happens to be a Mexican and an undocumented immigrant, we would have enough positive interactions with Mexicans and other immigrants so as not to be misled by the video’s message.

Nobody is immune to illusory correlations and other cognitive biases. Whether watching the news or drawing conclusions about other people from new information, we all need to be reminded to think critically. Even if some of us still choose not to trust undocumented immigrants, let us base our decisions on the type of evidence that would satisfy scientists—not fear-based assumptions and deceptive campaign ads that prey on our insecurities.

References

1. Chapman, L. J. (1967). Illusory correlation in observational report. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6, 151–155.

2. Hickman, L. J., Suttorp, M. J. (2008). Are deportable aliens a unique threat to public safety? comparing the recidivism of deportable and nondeportable aliens. Criminology & Public Policy, 7, 59-82.