Loneliness

The Japanese Art of Loneliness

Loneliness is a rich human experience if we can open to it.

Posted September 10, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

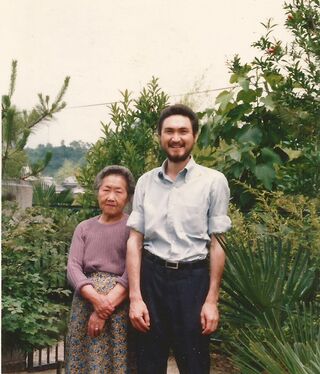

It was our last supper together. In the morning I would leave home to attend university in Tokyo. Grandmother would be alone, again. I became sad at the thought of leaving her and said, “You'll be lonely, won't you?” But she surprised me by saying, “That's OK, I like loneliness.”

I thought she was just acting bravely. I knew that she had been devastated when we — her daughter, her only child, three grandchildren and my dad—left her behind to go to America. But she was 50 years old then, now she was nearly 80.

The Japanese word sabishii means lonely, but my grandmother’s way of using it seemed to have a deeper meaning. Perhaps to her it was the human condition to be lonely, so that being mindful in those moments connected her to others, because we all experience this sadness that is part of life. Grandmother’s way of living was a mature acceptance of loneliness, the suffering in existence, and the impermanent nature of human experience. Loneliness reminds us that we know love. I felt that there was dignity, sacrifice and service in my grandmother's way of doing her part, freeing me to pursue my path.

Sabi represents the material aspects of life, the loss of that which sparkles, and the fleeting nature of beauty. Like my grandmother, sabi things carry the burden of aging with dignity and grace. Although I didn't understand it at the time, her feelings make sense when I realize that the word “sad” comes from the same Latin root as the words “sated” and “satisfied,” indicating that it may actually be a kind of fullness—in this sense, a fullness of heart. We feel sad when our heart is full, tender, and alive, as opposed to the frozen state of depression.

Deep acceptance and understanding of our pain make it possible to convert weakness into strength and offer our own experience as a source of healing to those lost in the darkness of their own sufferings. We are not alone. We are deeply interconnected with others, past and present. And yet we are alone. We are both not alone and alone. Though we search for the magical solution to ending this aloneness, we never find it.

Mono no aware expresses compassion and sadness in our awareness of the transience of all things, which in turn deepens our appreciation of their truth or beauty. The love of the glorious ephemeral beauty of cherry blossoms is characterized by mono no aware. This compassionate sensitivity is perhaps what my grandmother was describing.

Today loneliness is a rampant social problem. Elderly people and many others live alone and without social contact. We need to rebuild community support and respect for elders. We also each need to grow our abilities to find meaning in loneliness.

In my 20s I couldn't see what I see now in my 60s. Loneliness is an escapable part of the human condition. We try to escape it in so many ways, but aging brings more solitude and loneliness. When we face and embrace loneliness our relationship to it shifts. If we engage and befriend loneliness it can be a natural part of life and bring us freedom.

We also embrace loneliness by internalizing lost loved ones. In a touching scene in The Lion King (2019), the young lion grieving his dead father is told, “He lives in you.” I often have this feeling when I say or do something and it reminds me of my father, grandmother, or some other departed loved one. I have the sense that they live on in me. I’m reminded of how my grandmother told me that we would never be apart because she would be in my heart.

The film The Shape of Water (2017) ends with this beautiful poem about death as an escape from the confines of a physical body, releasing the soul to a state that transcends material constraints, enabling constant connections and togetherness.

Unable to perceive the shape of you,

I find you all around me.

Your presence fills my eyes

with your love.

It humbles my heart,

for you are everywhere.

I remember the last supper I had with grandmother before setting out on my youthful journey with a growing sense of her mature appreciation of loneliness, her way of accepting loss as an integral part of life. I feel mellow and peaceful as loneliness reminds me that I know love.

I find fun ways to remember. Grandma passed away on February 22 and when I see the clock is 2:22, I imagine grandma is here. She was 111 and when I see 1:11, I remember her as well as my dogs who barked, “Wan Wan Wan!” Silly? Perhaps, but who cares? It sure feels good! In these moments I feel the presence of those who have left us. "I am here, for you,” they are telling me. Together, not alone in the delusion of separateness, I move and go about my day, remembering that I too am living and dying, no different from the way they once were on this earth and the beings around me still are.

That’s what we’re all doing—loving and losing, coming and going, living and dying. We do what we’re called to do here and then are called away, leaving those who remain behind with the challenge of making meaning of it all, or at least just moving on. And though I don't understand it, I draw strength in trusting that the departed are well, still by my side, or imagining that they live on in me.

References

From Mindfulness to Heartfulness (Berrett-Koehler, 2018); S. Murphy-Shigematsu