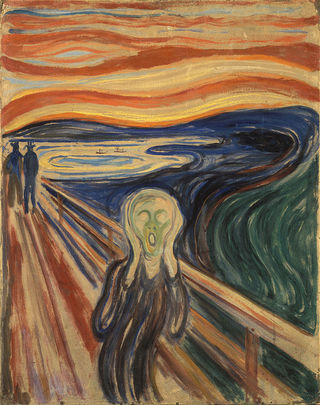

Anxiety

Collective Anxiety During the Pandemic Crisis

Why bad news turns us on, and good news bores us.

Posted March 29, 2020

Imagine two prehistoric hunter and gatherer individuals. They both are in need of information to make crucial decisions that will eventually determine whether they’ll live or die.

In the absence of Facebook or TV, they would get this information through their senses: their sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste. Suppose that these two individuals differ in their genetic profile. One of them pays attention only to bad news, e.g., the sound of an approaching bear, the taste of a poisonous fruit, or the smell of a fire. The other instead screens out bad news and pays attention only to good news: the sight of a sunny day and the smell of flowers. They both get the same information but process it differently.

It’s pretty clear who among the two would be happier and have a better life, but it is also clear who’ll live longer. In a harsh and dangerous environment, natural selection will favor the pessimist, worrier, and gloomy individual. The other one, who ignores the danger and sees the world in rose-colored glasses, is much less likely to survive and more likely to die before breeding and raising his offspring. Since we are all decedents of survivors who influenced our genetic profile, even dozens of millennia later, bad news turns us on, and good news bores us.

At times of public anxiety, false rumors of bad news spread and are believed exponentially faster than truthful good news. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, we have been flooded with apocalyptic predictions and mostly worst-case scenarios. Almost every ridiculous story would find willing ears. I have been personally exposed to one that claimed that the virus has already killed us all and that our current experiences are traces of pre-corona neural signals that are about soon die out soon as well.

Anxiety would make us spread bad news, hoping that recipients would refute them and ease our worry. But those recipients are not much different than us. Instead of contradicting them, they would spread them further. We would interpret such behavior as a confirmation to the veracity of the news. This would make us even more worried, and hence more willing to spread it further worrying others.

Just like the virus, fear and anxiety are contagious, but unlike the virus, meeting someone with anxiety will increase the level of your infection even if you were already infected with anxiety. Furthermore, being infected with anxiety makes people, albeit unconsciously, want to infect others. Just imagine how much faster COVID-19 would have spread if these spreading rules would have applied to the virus.

But there is another source of spreading anxiety in our time: Self-interested politicians, many of whom moved within days from ridiculing the concerns regarding the epidemic to horrendous forecasts regarding its consequences. The purpose of the first reaction is to appease the public with relaxing information and demonstrate a lack of stress, which is rewarding if the disease turns out to be mild. The second one is used as an insurance policy, guaranteeing that even if they do very badly in handling the epidemic, when it is all over, they would be able to claim the fame for saving the lives of millions by using their own horrifying and unrealistic forecasts as the benchmark for comparison. Alongside politicians, media outlets may often also be biased towards extreme pessimism, simply because, as noted above, good news doesn’t sell as good as bad news.

Anxiety not only makes it harder for us to go through many days of confinement and isolation, but it also affects the quality of our decision making at a time when we need it the most. Studies show that anxiety shuts down regions of the brain (prominently the pre-frontal cortex) that allow us to concentrate and screen out distractions. (See here.)

Anxiety forces our brain to consider every irrelevant piece of information that we face. Very often, it ends with a wrong decision that takes a lot of time to make.

Collective anxiety has no vaccine, but there are some remedies that need no prescription. Exercising informational-social distancing is one such remedy. At times of collective anxiety, social media dominates the news and gets no screening whatsoever. Extra skepticism regarding any piece of information, especially those that contain disturbing news, is much advised. Ask yourself whether the source has any motive or interest in exposing you to that information.

Our obsession to scratch another piece of evidence regarding the disease already several weeks into it is unlikely to offer any additional important and useful knowledge or to make us feel better. At a certain point, it is more helpful to present ourselves with a different type of food for thought. Planning our next vacation, for example, even without knowing when it might take place is likely to cheer us up much more.