Self-Help

How To Learn Self-Compassion at Home

Research Shows Teaching Oneself Self-Compassion Works

Posted December 29, 2017

"My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style."

— Maya Angelou

The growing evidence for compassion-based approaches

Drawing upon Eastern religious and philosophical practices including tonglen and metta meditation operationalized within a Western psychological framework (an oversimplification), compassion-based approaches are gaining in popularity, following in the tradition of mindfulness-based approaches while incorporating deliberate efforts to promote positive and loving feelings toward oneself and others.

A growing body of research literature suggests utility for compassion-based approaches in a variety of settings. I have found compassion-based approaches to be useful in my clinical practice, and in my personal life—sometimes transformative, typically very helpful. Occasionally, compassion-based work is too triggering for those unable to intentionally focus on self-regard, including those with high fears of compassion often associated with developmental trauma, who may require preparatory work to arrive at a position where they can directly contemplate self-care without excessive distress.

Compassion-based approaches include structured therapies as well as self-guided or meditation-based work. Smaller research studies have shown compassion-based approaches to be helpful in reducing distress and improving outcomes and well-being in people with psychotic disorders (Braehler et al., 2014), eating disorders (Kelly & Carter, 2015), sexual pain disorders (Santerre-Baillargeon et al., 2017), and in those working on smoking cessation (Kelly et al., 2010), body image issues (Seekis et al., 2017), for women dealing with domestic violence (Karakasidou & Stalikas, 2017), in non-clinical groups (Aramitsu, 2016) and for those vulnerable to depression (Shapira & Mongrain, 2010). These studies have shown positive effects for compassion-based approaches including Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT), but have looked at small sample sizes over a short time period.

The current study

In order to see if the benefits of Compassion-Focused Therapy carry over to a larger group over a longer period of time using a guided self-help protocol as a model for public health intervention, researchers Sommers-Spijkerman and colleagues (2017) developed a randomized, controlled prospective study to assess the effectiveness of CFT for large group of people with diminished levels of well-being. Subjects were recruited through newspaper ads, and were eligible for the study if they met criteria for low well-being and poor function as measured by the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. Applicants who reported symptoms consistent with a clinical diagnosis (e.g. anxiety or depression) were referred for treatment and not included in the study. This left a group of 243 participants who were experiencing significant difficulties, not to the degree that they required immediate medical attention.

From this group, individuals were randomly assigned to either an intervention group or to a waiting list control group, who received no immediate intervention. The average age of participants was 53 years, three-quarters were women, and the majority were educated. Most were employed and over half were married and/or living with a partner. The intervention and wait list groups were similar to one another demographically.

The intervention

Those in the intervention group received a self-help book (Compassion as Key to Happiness, 2015), based on Paul Gilbert’s (2014) model of Compassion-Focused Therapy. They could choose from among a variety of interventions geared to foster well-being by using compassion-based practices to increase factors including motivation for self-care and improvement in distress tolerance.

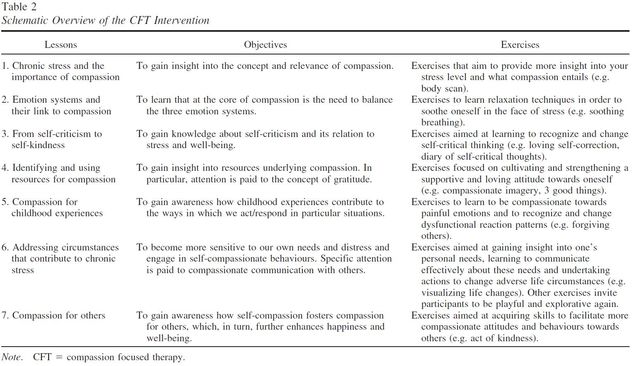

Exercises were presented as weekly lessons with a core focus and multiple exercises designed to address different aspects of compassion, including mindfulness practice, tracking self-critical thoughts, using letter writing exercises, and imagining one’s ideal compassionate self, among others (See Table below). Participants were instructed to complete one lesson per week for several weeks, selecting whatever exercises were most suited for their current circumstances. Participants were provided with weekly email-based guidance, which has been shown to improve self-help adherence and effectiveness. At the end of the study, wait list participants received the same intervention without email support in order to look at the effect of receiving guidance.

Measures

Outcome measures included past month well-being using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form, looking at emotional well-being, psychological well-being and social well-being, including a category for flourishers vs. non-flourishers; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the Perceived Stress Scale; the Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale; the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form; the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; the Gratitude Questionnaire; an assessment of adherence with the intervention looking at lesson completion, time spent doing exercises, satisfaction with the intervention, perceived changes during the intervention, and related considerations; and healthcare use (primary care, mental health, and self-help). Follow-up extended from baseline to 9 months post-intervention.

Findings

Participants in the intervention group had lower rates of drop-out over the course of the study and spent significantly more time on Compassion-Focused Therapy than those in the unguided group. There were no differences in healthcare utilization between the intervention and the control group up to 3 months after they competed CFT. In the first months following completion, the intervention group showed statistically significant improvement on all outcome measures, including moderate to large effect sizes on increased emotional well-being and reduced self-criticism.

On longer-term follow-up, in the 3 to 9 months following the intervention, there were significant improvements in positive emotions, and most notably reduced stress, and initial improvements were maintained. At 9 months, nearly 40% of the CFT group, representing those who completed the full intervention, reported clinically significant improvements in well-being and were flourishing. Participants who received guidance showed statistically significant improvement in multiple domains, including general and specific (social and emotional) measures of well-being, anxiety, self-compassion, self-criticism, self-reassurance and gratitude. The group without guidance showed less robust but still significant improvement, and adherence was higher in the email support group.

Further considerations

This larger, prospective, longer-term follow-up supports the prior research findings that compassion-based approaches can be useful in a non-clinical sample for promoting well-being and positive self-regard as reflected across multiple outcome measures. Furthermore, this study is proof-of-concept that Compassion-Focused Therapy can be effective as a form of structured self-help, and is even more effective when delivered with digital guidance to encourage robust participation.

Given high rates of distress and poor general, emotional and social well-being for many people as reflected in clinical and non-clinical populations suffering from high rates of depression, anxiety, general health problems, stress, burnout and other issues, compassion-based practice is a relatively simple, cost-effective and accessible approach which offers significant relief.

Future research should look at longer-term follow-up in larger groups for a broader array of health and wellness outcomes to determine who can benefit most and what components are most effective in what circumstances, and to understand the impact of ongoing compassion-based work in more vulnerable groups including those with specific clinical conditions as well as in non-clinical populations. As long as one is able to fruitfully build self-compassion without triggering excessively strong reactions (in which case additional assistance is appropriate), compassion-based self-help approaches should be considered for useful inclusion in our self-care routines.

Resources:

The Compassionate Mind Foundation, Dr. Paul Gilbert

Dr. Kristen Neff, Mindful Self-Compassion

Greater Good In Action, Berkeley

Emory-Tibet Partnership, Cognitively-Based Compassion Training

References

Arimitsu, K. (2016). The effects of a program to enhance self-compassion in Japanese individuals: A randomized controlled pilot study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 559–571.

Braehler, C., Gumley, A., Harper, J., Wallace, S., Norrie, J., & Gilbert, P. (2013). Exploring change processes in compassion focused therapy in psychosis: Results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52, 199–214.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 6–41.

Hulsbergen, M., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2015). Compassie als sleutel tot geluk: Voorbij stress en zelfkritiek [Compassion as key to happiness: Beyond stress and self-criticism]. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Boom.

Karakasidou, E., & Stalikas, A., (2017). Empowering the battered women: The effectiveness of a self-compassion program. Psych, Vol. 8, No. 13, November.

Kelly, A. C., & Carter, J. C. (2015). Self-compassion training for binge eating disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88, 285–303.

Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., Foa, C. L., & Gilbert, P. (2010). Who benefits from training in self-compassionate self-regulation? A study of smoking reduction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 727–755.

Shapira, L. B., & Mongrain, M. (2010). The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 377–389.

Santerre-Baillargeon, M. O., Rosen, N., Steben M., Myriam, P., Macabena-Perez, R., & Bergeron, S. (2017). Does Self-compassion Benefit Couples Coping with Vulvodynia? Associations with Psychological, Sexual, and Relationship Adjustment. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 21, December.

Seekis, V., Bradley, G. L., Duffy, A., et al. (2017). The effectiveness of self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks in reducing body image concerns. Body Image, December, 206-213.

Sommers-Spijkerman, M. P. J., Trompetter, H. R., Schreurs, K. M. G., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017, December 21). Compassion-Focused Therapy as Guided Self-Help for Enhancing Public Mental

Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Advance

online publication.