Aging

Experiencing Aging in Your Mid-Twenties

How studying aging actually improves your aging process.

Posted June 27, 2018

An ophthalmologist, my husband Jack underwent years of medical training. When he reflects on this time – particularly the earliest parts of it—he, like many of his ilk, admits to at least a fleeting period of preoccupation with getting or having the symptoms of the diseases he studied.

I’ve always wondered, when regaled with his harrowing clinical tales, if such an analog to medical-student syndrome exists and what it might look like for my colleagues and I who study gerontology. The closest I suspect I’ve gotten happened once while administering a cognitive status exam, questioning anxiously if I had a touch of impairment when I couldn’t easily recall the five objects I had just read aloud. Does that count? You decide.

In any case, questioning the existence of such an analog presupposes aging as a disease, which, to the dismay of Aubrey de Grey, has little support. Self-deprecating jokes aside, if it does exist, perhaps it assumes the form of something like an equal and opposite force to medical student syndrome—Adaptive gerontological exposure syndrome (AGES)—whereby gero disciples like me self-consciously experience ourselves as aging beings, behave, and profit accordingly.

At 26, I’m definitely symptomatic. When people ask why I study aging, I proffer up a catalogue of reasons that always includes how gerontology enhances my own aging process. To combat the flummoxed glances my reply elicits, I typically volley back the following four reasons:

1. Studying aging may confer unique protective benefits.

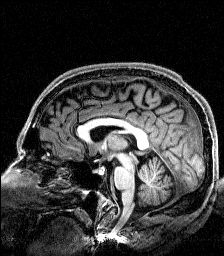

Increasing evidence suggests that, through a series of behaviorally mediated processes, negative age stereotypes harbored across the life course can predict a wide range of health outcomes including cardiovascular disease and depression. Recent findings even reveal that adults with more negative age stereotypes earlier in life evinced more Alzheimer’s-disease biomarkers later, including steeper hippocampal density loss as well as greater accumulation of tangles and amyloid plaques. If Allport’s (1954) contact hypothesis stands—that under appropriate conditions, interpersonal contact can deconstruct negative stereotypes assigned to outgroups—then studying aging itself can interrupt and correct internalized stereotypes believed to contribute to adverse health outcomes.

2. “Health interest” compounds.

Gerontologists consume, generate, and apply hot-off-the press, evidence-based research to understand and promote successful aging—but the routes to reducing disability, increasing functioning, and enhancing life engagement apply across the human lifespan. We know what predicts longevity and how to apply it and the earlier we start applying, the better. Securing seven to nine hours of sleep, for example, will clear out beta amyloid plaque at ages 18, 80 or 108. Volunteering confers physical and psychological benefits at any age. And cardiovascular exercise will densify the hippocampus no matter how gray the stuff between your ears. The health literacy internalized from practicing evidence-based gerontology compounds like interest, accumulating over time to yield higher returns later in the life course.

3. Older adults provide stories and maps. Stories and maps provide guidance.

Healthy or otherwise, lifespans tell stories and gerontologists interpret them. Stories have value because they yield the benefits of experience without the high costs of its lessons. In this way, gerontology represents an extended exercise in social learning, providing interested students of life with a comprehensive, longitudinal data set of tried-and-true variables tied to longevity. Gerontologists get privileged, real-time insight into what “works” and what doesn’t—what to approach and to avoid, permitting the “trying on” in our mind’s eye of different things in which to outfit our lives through the protective, warm embrace of wisdom. With enough attention and conscientiousness, those stories can morph into maps that help to orient observers toward healthy, long, and engaged golden years.

4. You learn how not to sweat the small stuff.

As their time horizons shrink, older adults tend to selectively and systemically hone their social experiences to meet shifting emotional needs. These motivational shifts produce a contagious don’t-sweat-the-small-stuff-ness that, under lucky conditions, can prematurely seep into other developmental epochs. Appropriate seepage can buffer the untamed cascades of cortisol flowing from pesky peer reviewers, professional pressures, traffic, and the general existential dread accompanying a Type A-personality-plagued adulthood. For me, all of it sort of assumed laughable smallness after really grappling with the big metaphysical stuff built into gerontological work like life, death, meaning, love, and loss. Now, better than ever before, I can ask myself compassionately: “Will this matter when I’m 60? 70? 80?” and can almost always answer “no” honestly. Reducing my cortisol levels alone has probably added another five years to my life.

Someone once said we study our pathologies. While I respectfully disagree, I hope whoever said it at least aged well.

Talk to your doctor today about AGES.