Creativity

Creative Thinking in Crisis Psychology

Accepting and expecting the unexpected in crisis psychology.

Posted July 28, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Creative thinking in crisis psychology can help morph the unexpected and the unknown into crises avoided.

- Many psychology techniques can support this approach, especially variations of having a devil’s advocate.

- With imagination and initiative, the impact of “unknown unknowns” can be reduced.

"Surprise!"

It can be fun if it involves a birthday party or other celebration. It is less enticing when a danger or threat should have been anticipated, but was not.

Part of crisis psychology is investigating how to avoid a crisis. What actions could be taken in advance of a threat to ensure that a threat does not become a crisis? How could these actions be implemented before it is too late by those with the political power and resources to do so?

The people who died in Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and during the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks were not to blame (apart from the terrorists in the latter). Those who had the information and opportunities available beforehand for stopping the disasters lacked the mindset to act competently in time. The U.S. House of Representatives’ Select Bipartisan Committee’s report into Hurricane Katrina was titled “A Failure of Initiative.” The 9/11 Commission explained that, “It is therefore crucial to find a way of routinizing, even bureaucratizing, the exercise of imagination."

Initiative and imagination can prevent and overcome unwelcome surprises. Crisis psychology offers specific ways of creative thinking for it.

Creative thinking

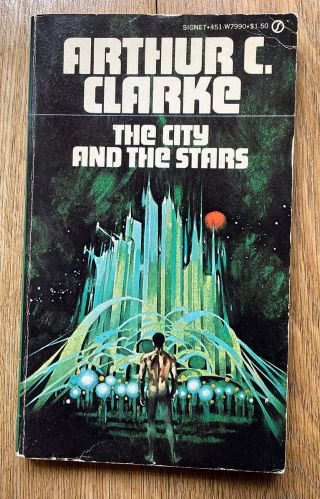

Arthur C. Clarke’s 1956 novel The City and The Stars includes the character of the Jester. Rather than being a joker or a fool for comedic entertainment, this Jester’s job was to break people’s routines so that they think differently, considering alternative actions. The Jester forced people outside of their comfort zones to stop them from doing exactly the same in exactly the same way.

How many boardrooms or government cabinets have a jester cajoling members to consider data and policies from new angles? How many times are we rewarded by offering advice which seems ridiculous, and is, yet inspires new and previously unconsidered directions?

Another articulation in various forms, including in the movie World War Z under the non-gender-neutral guise of the “Tenth Man Theory,” is always having a dissenter. If a group of 10 makes decisions, the notion is that when nine people agree, then the 10th must raise disagreements and counterproposals. Similarly, Red Team Analysis, Red Team Thinking, and Red Teaming aim to present an adversary’s perspective to assist decisions. It could be extended to examining problems and solutions from numerous cultural and experiential viewpoints.

Generalizing, if a certain number of people agree on an interpretation or an action, then find someone else to offer alternatives and argue against the consensus. This “n+1th Person Technique” or “One More Person Theory” could be enacted as teams rather than as individuals.

These suggestions are, of course, more precise formulations of what is commonly known as the Devil’s Advocate. What is unusual in many decision-making circumstances today is ensuring that someone becomes the Devil’s Advocate and then really listening to and responding to what they express.

Is it really a surprise?

The question remains how much unconventional thinking really does contribute to crisis psychology. After all, uncreative, predictable scenarios with precedents seem surprising when they manifest.

Louisiana and Mississippi sit in a hurricane zone, they have had severe hurricanes before, and it was hurricane season when Katrina made landfall. Neither the mayor of New Orleans (later imprisoned for bribery and fraud) nor the head of the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (who had had close to zero pre-FEMA crisis-related experience) should have been surprised by Hurricane Katrina.

Prior to 9/11, al-Qaeda had tried to destroy the World Trade Center with a truck bomb in 1993, while both fiction and reality provided examples of terrorists trying to use airplanes to destroy iconic buildings. In December 2000, a Gatwick-to-Nairobi jet nearly crashed when a passenger breached the flight deck and knocked the controls. Israel’s flag carrier, El Al, had long had secure cockpit doors and procedures as well as plainclothes armed guards aboard, among many other layers of security.

With imagination and initiative supported by leadership, many foreseeable situations do not need to become surprises or crises. Few so-called “black swans” are real. Who, when, where, and why might be unknown. What and how can be worked out and can be used to develop scenarios and readiness?

Unknown unknowns

Not that what and how can always be determined beforehand. As mooted in 1969, “unknown unknowns” exist. Not all earthquake faults have been fully mapped. An unstudied mountain can flare into a volcanic eruption. Before July 16, 1945, it was not clear that nuclear bombs could be built—or detonated without destroying the planet.

Scientists and political leaders had the imagination to speculate about atomic bombs and the initiative to pursue them, for good or bad. This article provokes the imagination to consider unknown earthquake faults and volcanoes. Who provides the initiative through resources and leadership to seek them out?

It means going beyond the adage of “expect the unexpected.” Expect it, yes, but also accept that creativity through unpredictable thinking can reduce the chance of an unpredictable situation—and then a crisis.

References

Campbell, R.R. 1969. “The arms procurement art”. Ordnance, 54, 297, 306-309.

Clarke, A.C. 1956. The City and the Stars. Signet, New York.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. 2004. The 9/11 Commission Report. United States Government, Washington, DC.

Streets, D.G. and M.H. Glantz. 2000. Exploring the concept of climate surprise. Global Environment Change, 10, 2, 97-107.

US House of Representatives. 2006. A Failure of Initiative: Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina. 109th Congress, 2nd Session, Report 109-377. United States Government, Washington, DC.