Education

Discovering Natural Selection Was Like "Confessing a Murder"

Darwin's hesitancy to publish about evolution as self-censorship in science.

Updated December 13, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer Ph.D.

Key points

- Darwin's hesitancy to publish on the evolution of life stands as an exemplar of self-censorship in science.

- Darwin's ultimate decision to publish about evolution shaped our understanding of the world profoundly.

- To the extent that scientists hold onto critical findings, they're doing a disservice.

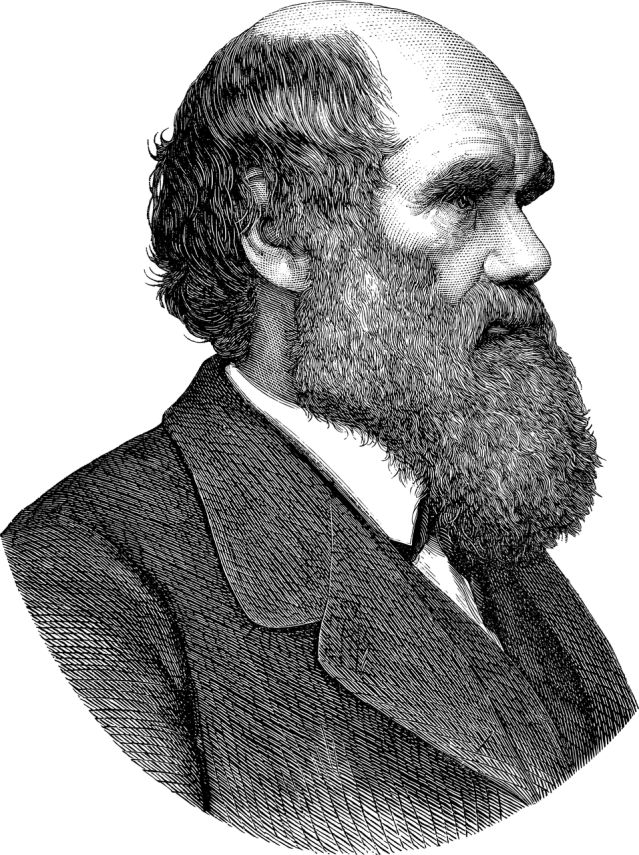

Between 1831 and 1836, Charles Darwin circumnavigated the globe as the naturalist for the renowned HMS Beagle. Darwin's task, as far as Britain was concerned, was to discover and describe flora and fauna from across the globe. Along the way, Darwin famously discovered the principles of natural selection, which serves as the primary evolutionary force that came to shape the nature of life itself (see Eldredge, 2005).

A devout Christian, and relatively quiet man—not known as someone who was interested in making waves—Darwin sat on his ideas regarding evolution for more than two decades. After much time, and in light of various communications with other scholars at the time, Darwin (1859) finally got around to publishingThe Origin of Species (often referred to simply as Origins)—one of the most important books in the history of science, and one that would radically and permanently change our understanding of life itself.

With regard to having discovered the process of natural selection, in 1844 Darwin wrote in a letter to a close confidante (botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker), "It is as if one were confessing to a murder."

Darwin reported vomiting regularly thinking about the implications that his ideas would have for our understanding of what it means to be human.

Darwin, Natural Selection, and Self-Censorship

In a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (Clark et al., 2023)—a paper that I feel fortunate to have co-authored—a case is made that perhaps the most prevalent form of censorship in science might be considered "self-censorship" (see my Psychology Today piece on this concept here). Self-censorship in science essentially exists when a scientist is hesitant to present some findings or ideas—for a number of potential reasons—and ends up refusing to disseminate said ideas or, in some cases, delaying dramatically the presentation of said ideas.

Not sure about you, but to my mind, the fact that Darwin discovered natural selection in the 1830s, yet didn't publish his main expose on the topic until 1859,* tells a profound story of self-censorship in science. It literally took him a quarter of a century—along with a good bit of nudging by other scholars and confidantes (such as Alfred Russell Wallace)—to disseminate a set of ideas that would change the world forever.

To be fair, evolution and its underlying processes, such as natural selection, have famously been considered controversial for a broad array of reasons since the publication of Origins (see Wilson et al., 2019). So his hesitancy to publish these ideas is kind of understandable.

But gosh, think about how much our understanding of the world and of our place in it have advanced due to Darwin's influence.

According to renowned geologist Warren Allmon (2011), the field of Biology didn't even exist as an area of academic inquiry until after the publication of Origin. Think about that.

Further, to say that understanding evolution helps us to solve all kinds of human problems would be a profound understatement. Evolutionary concepts, which all trace back to Darwin, have advanced our understanding of such critical facets of the human experience as:

- Education (see Gruskin & Geher, 2018)

- Mental health (see Nesse & Williams, 1995)

- Physical health/medicine (see Wolf, 2010; Platek et al., 2011; Nesse & Williams)

- Nutrition (see Guitar, 2017)

- Politics (see Geher et al., 2015)

- Social media (see Geher & Wedberg, 2022)

- Human emotions (see Nesse & Ellsworth, 2009)

And more.

Relative to where we are now, without Darwin's courageous decision to publish Origins, we'd pretty much be in the Dark Ages.

Given the profound shift in our understanding of what it means to be human that was brought about by the publication of Origins, it's not too hard to see why Darwin engaged in such self-censorship for so many years. Unleashing the idea of natural selection truly was, in his words, like confessing a murder.

Bottom Line

In a recent paper on censorship in science, Clark et al. (2023) make a strong case that scientists engage in self-censorship with some regularity. Here, I briefly summarize the story of Darwin and the highly lagged dissemination of one of the most profound ideas in human history: natural selection. We can easily think of this decades-long lag in the publication of natural selection as a truly impactful case of self-censorship in science.

While Darwin clearly wrestled with the idea of publishing his findings about natural selection intensively, I'm thankful that, at the end of the day, he chose the courageous path and went ahead and published these ideas in his landmark work The Origin of Species (1859).

Not all research findings are going to be popular. And not all scientific ideas are going to be loved by all. But publishing ideas and findings that might cut against the grain, at the end of the day, helps us better understand the nature of the world. And that, as I see it, is kind of the point of science. Right?

___________________________________________________

*He did give some minor presentations on these ideas to small, professional audiences prior to this point (such as a talk on these ideas at a meeting of the Linnean Society of London in 1858)—but none of these presentations really took hold. It wasn't until the 1859 publication of Origins that the concept of natural selection truly was unleashed.

References

Allmon, W. D. (2011). Why don’t people think evolution is true? Implications for teaching, in and out of the classroom. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 4, 648-665.

Clark CJ, Jussim L, Frey K, Stevens ST, Al-Gharbi M, Aquino K, Bailey JM, Barbaro N, Baumeister RF, Bleske-Rechek A, Buss D, Ceci S, Del Giudice M, Ditto PH, Forgas JP, Geary DC, Geher G, Haider S, Honeycutt N, Joshi H, Krylov AI, Loftus E, Loury G, Lu L, Macy M, Martin CC, McWhorter J, Miller G, Paresky P, Pinker S, Reilly W, Salmon C, Stewart-Williams S, Tetlock PE, Williams WM, Wilson AE, Winegard BM, Yancey G, von Hippel W. Prosocial motives underlie scientific censorship by scientists: A perspective and research agenda. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 Nov 28;120(48):e2301642120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2301642120. Epub 2023 Nov 20. PMID: 37983511.

Darwin, Charles (1859). The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1st ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 1-4353-9386-4.

Eldredge, N. (2005). Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life. Norton.

Geher, G., Carmen, R., Guitar, A., Gangemi, B., Sancak Aydin, G., and Shimkus, A. (2015) The evolutionary psychology of small-scale versus large-scale politics: Ancestral conditions did not include large-scale politics. European Journal of Social Psychology, doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2158.

Gruskin, K., & Geher, G. (2018). The Evolved Classroom: Using Evolutionary Theory to Inform Elementary Pedagogy. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 12, 1-13.

Nesse RM, Williams GC: Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine, Times Books, New York, 1995.

Nesse,R.M., & Ellsworth, P.C. (2009). Evolution, emotions, and emotional disorders. American Psychologist, 64, 129–139.

Platek, S., Geher, G., Heywood, L., Stapell, H., Porter, R., & Waters, T. (2011). Walking the walk to teach the talk: Implementing ancestral lifestyle changes as the newest tool in evolutionary studies. Evolution: Education & Outreach, 4, 41-51. Special issue on EvoS Consortium (R. Chang, G. Geher, J. Waldo, & D. S. Wilson, Eds).

Wolf, R. (2010). The Paleo Solution. Las Vegas, NV. Victory Belt Publishing.