Suicide

How Can We Optimize the Lives of Suicide Survivors?

A blueprint for bolstering long-term well-being.

Posted February 25, 2021 Reviewed by Matt Huston

You might have read one of several tomes showing how the world is getting better despite our intuitive belief that things are getting worse. With meticulous data, it is hard to argue with the evidence in Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now, Gregg Easterbrook’s It’s Better Than It Looks, or Hans Rosling’s Factfulness. Pinker succinctly points out,

“An American in 2015, compared with his or her counterpart half a century earlier, will live nine years longer, have had three more years of education, earn an additional $33,000 a year per family member…and have an additional eight hours a week of leisure.”

Easterbrook offers a similar pronouncement:

“If your great-great grandmother had known that today nearly everyone in the West, and an ever-increasing share of those in developing nations, would live in a society with plentiful food and fuel; with most infectious diseases thwarted; with fast, very-low-risk transportation available to most men and women, including average people traveling aboard jets; with nearly every adult a high school graduate and 470 million people worldwide holding college degrees; with inexpensive, instantaneous global communication available to most of humanity; with more people in desk jobs than sweating in mines or on assembly lines — your great-great grandmother would say the present represented her era’s dream come true.”

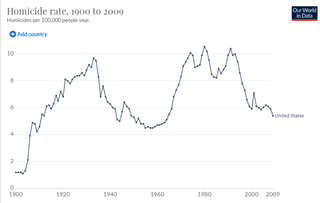

The most objective metric of violence available, the presence of a dead body, offers a perspective of how much better society is faring. These large declines in fatalities extend to non-fatal crimes. For instance, according to child protective services official reports, from 1992 to 2012, “substantiated sexual abuse declined by 62%, physical abuse by 54%, and neglect by 14%.”

Yet, people are not happier.

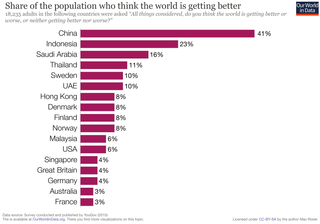

If you want to know who is unhappiest, look no further than income, education, and occupational prestige. In a nationally representative sample, adults in the bottom half of income earned showed a systematic decline in happiness from 1970 to 2018. Adults without a college degree, and lacking occupational prestige, showed a similar decline in happiness from 1970 to 2018. No such declines were found for adults in the upper echelon of income, possessing occupational prestige, or with a college degree. While the world is improving, people’s attitudes and feelings are often pessimistic, especially in the United States. There might be a decline in wars, violence, and child maltreatment, but there is one metric that continues to rise: suicide rates.

Irrespective of objective improvements in quality of life, a lot of misery exists. Since 2008, suicide remains one of the 10 leading causes of death. For the past 20 years, suicide increased approximately 1-2% per year. In the past year, 12 million American adults seriously contemplated suicide, 3.5 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.4 million attempted suicide. A great deal of effort is devoted to preventing suicide and aiding those wondering whether life is worth living.

Our research team is exploring a different question. How often do people not only recover but improve their lives with such proximity to intentional death? These are people who gained a second chance at living. What changes do they make? Who is most likely to make positive changes to their habits, routines, relationships, personal goals, and allocation of money, time, and effort?

Surprisingly little research exists on the aftermath of emotional difficulties or in this case, people who have survived suicide attempts. A half century of research exists on risk factors that precede the onset of suicidal thoughts and gestures. In contrast, we know much less about what factors aid people in returning back to their lives and achieving what everyone wants: a life of happiness, a life of meaningfulness, a life of psychological richness.

At this point, we have only important glimmers of relatively favorable outcomes after non-fatal suicide attempts. To spur researchers and practitioners, my colleagues and I offer suggestions for how to better study, understand, and improve the lives of people who came close to killing themselves. Here are four initial questions:

1. How common is psychological well-being after suicide? One benchmark comes from our recent research on the possibility of achieving high functioning after depression. In a nationally representative sample of United States adults, approximately 10% of individuals suffering from major depressive disorder not only recover but function at exceptionally high levels in multiple domains of well-being 10 years later.

Well-being after having survived a suicide attempt may be lower than this due to various reasons, such as social stigma, lack of support, self-blame and devaluation. Even if it turns out to be uncommon, there are questions about the underlying mechanisms distinguishing a path to health and well-being from a path characterized by suffering and recurrent suicidal behaviors.

2. What is the role of clinical correlates for predicting long-term well-being after suicide attempts? Do psychological difficulties such as depression impact the likelihood of suicide attempt survivors achieving long-term psychological well-being? There has been evidence from cross-sectional studies that a low level of well-being is associated with higher levels of suicidal intent and depression. The interplay between depression and long-term well-being in suicide attempt survivors is unclear. The same question can be extended to other clinical issues such as traumatic events, substance abuse, ADHD, and chronic health conditions. These explorations can help us determine what serves as risk and resilience factors across life trajectories.

3. What differentiates suicide attempt survivors who achieve well-being from those who do not obtain such desirable outcomes? One hypothesis is that compared to peers who do not obtain such desirable outcomes, suicide attempt survivors who achieve well-being are higher on psychological flexibility and more likely to find an alternative solution rather than ruminating on the suicide attempts. It will also be important to study what types of emotion regulation strategies are used, what information is attended to following positive and negative daily events, and how their sense of self and their belief in their skills, strengths, and capacities develops and changes. In addition, the healing process after surviving a suicide attempt is rarely a solitary experience—it often involves family members, mentors, and friends. It will be important to understand the social capital of people dealing with suicidality. For instance, what are the well-being levels of caregivers? How do friends communicate and what judgments arise when interacting with a suicide attempt survivor? We must know more about what social elements enhance or minimize the probability of achieving long-term well-being.

4. Will the experience of having survived a suicide attempt trigger processes, such as meaning-finding, that facilitate long-term well-being? This research question needs to be framed with caution. Again, we are not suggesting a suicide attempt experience is positive or healthy. Instead, we seek to understand the psychological interpretation and response to an undesirable situation. We wonder about the forms of post-traumatic growth that might exist in people who survived suicide attempts. Qualitative studies describe the experience of a “turning point,” a critical moment when suicide attempt survivors regained the hope to live and developed a sense of self-worth. It will be useful to analyze patterns of strength, resilience, motivation to live, and the search for, detection of, and creation of meaning, that manifest after having survived a suicide attempt.

Material improvements and luxuries are by no means predictive of subjective well-being. Suffering exists. Our ultimate goal is to reduce suffering and suicide attempts and enhance psychological well-being for suicide attempt survivors in the long-term. If the probability of achieving psychological well-being for suicide attempt survivors is more common than anticipated, this information must be delivered. It will be an opportunity to be honest and hopeful during the stages of recovery and beyond. We hope to newly appreciate the complexity and heterogeneity of people who grapple with suicidal urges and behaviors, and bolster the human quest for self-preservation and desire for a rich, fulfilling life.

For more, read our new article: Tong, B., Kashdan, T.B., Rottenberg, J., & Joiner, T.E. (in press). Future well-being among people who attempt suicide and survive: Research recommendations. Behavior Therapy