Ethics and Morality

The Role of Autonomy in Moral Behavior

Autonomy provides perspective that makes moral behavior more effective.

Posted April 11, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Inner-directed people tend to act in socially conventional ways, while outer-directed people use others to guide their behavior.

- Autonomous people reflect on their reasons for following or ignoring moral conventions and social trends.

- The perspective that autonomy adds to inner- and outer-directedness can increase one's effectiveness as a moral agent.

Two of my previous posts on moral development described the origins and consequences of following inner expectations and others' expectations. We form our inner expectations (conscience, or what we expect from ourselves) when we unreflectively absorb rules from our parents. Inner-directed people (people who follow inner expectations rather than others' expectations) tend to behave in socially conventional ways. Responsiveness to others' expectations originates in empathy or caring about others and a desire to be well-liked. People who are other-directed use current trends and the opinions of close friends as a guide to right and wrong.

The Four Moral Personality Types

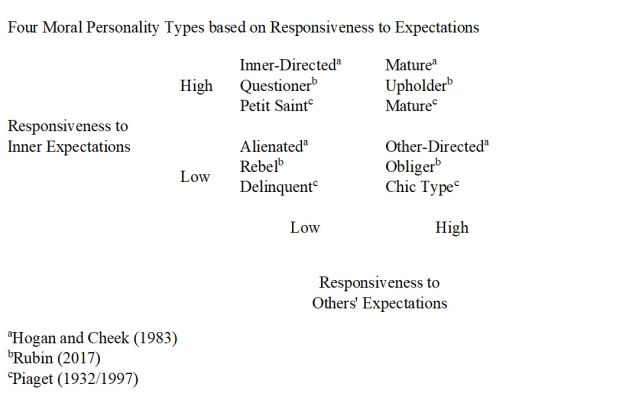

Responsiveness to expectations is a matter of degree. It is possible to be responsive to either inner or outer expectations, or both, or neither, which leads to the four types of moral personalities described by Hogan and Cheek (1983), Rubin (2017), Piaget (1932/1997) and others (see diagram).

However, one element missing from these discussions of responsiveness to expectations is the role of autonomy in moral behavior. Durkheim (1925/2002), Riesman (1961), Piaget (1932/1997), and Hogan (1973) all talk about autonomy as a third stage of development beyond the development of conscience and empathy, so how does autonomy relate to inner and outer expectations?

What Is Autonomy?

Autonomy is often confused with inner-directedness because inner-directed persons seem to be independent and self-sufficient, following their own "internal gyroscope" and not caring what other people think. Even Cheek and Hogan (1983) refer to their Inner-Directed type as autonomous. But this ignores the original source of the inner-directed person's internal gyroscope, which was his or her parents. The Inner-Directed type's internalization of parental rules and values was so successful and so complete, that this type is not aware that his or her strongly held beliefs and opinions are not freely chosen but are the result of early parental influence.

Riesman (1961) wrote extensively about the nature of autonomy and how it transcends both inner-directedness and other-directedness. Autonomy is difficult to define and measure, but it involves the perspective and detachment that arise from self-examination and an awareness of one's reasons for making choices. Whereas inner-directed people unreflectively imitate their parents and other-directed people unreflectively imitate their peers, autonomous people reflect on their reasons for following or ignoring moral conventions and social trends.

Autonomy Makes Our Moral Behavior More Effective

One way of understanding autonomy and its benefits is to look at what can happen when people respond well to moral expectations but lack autonomy. In this analysis, lack of autonomy can make a difference between healthy, effective behavior and unhealthy behavior. Three forms of non-autonomous behavior were described in an article I coauthored with Hogan and Emler (Hogan, Johnson, & Emler, 1978) and in a previous post. Below is the gist of what I had written previously.

Hogan, Johnson, and Emler (1978) outline three patterns of non-autonomous moral conduct: moral realism, moral zealotry, and moral enthusiasm. A moral realist is a former petit saint (inner-directed type) who, even as an adult, never developed an awareness of the purpose of following conventional rules. The moral realist's over-accommodation to authority and institutionalized rules leads to rule following as an end in itself, even when such behavior is self-destructive or harmful to others. Moral zealots are former chic types (other-directed types) who enjoy aggressive confrontations such as mob protest and even terrorism in the name of social justice, unaware that they are partially motivated by hostility toward authority. Finally, we have moral enthusiasts, who are responsive to both inner and outer expectations and are therefore generally good citizens, but they lack the perspective that comes with autonomy. Because of their lack of perspective, moral enthusiasts become swept up in popular moral causes, failing to discern the relative importance of different social issues or the actual consequences of their behavior. This lack of awareness diminishes their effectiveness as moral agents.

What autonomy adds to inner-directedness and other-directedness is thoughtful, deliberate reflection about the likely consequences of one's behavior. Autonomy by itself is passionless and has no motivating force. In fact, an autonomous person unresponsive to inner and outer expectations could be a rebel, delinquent sociopath interested only in personal gain. On the other hand, when a person is motivated by inner or outer expectations (or both), autonomy can help the person to achieve the desired aims of these motives (maintaining the established moral order; promoting social solidarity) by carefully considering the actual likely consequences of different courses of action.

References

Durkheim, Émile. (2002). Moral Education. (E. K. Wilson & H. Schnurer, Trans.). Mineola, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1925 as L'éducation Morale by Libraire Félix Alcan.)

Hogan, R. (1973). Moral conduct and moral character: A psychological perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 79, 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033956

Hogan, R., & Cheek, J. M. (1983). Identity, authenticity, and maturity. In T. R. Sarbin & K. E. Scheibe (Eds.), Studies in Social Identity (pp. 339-357). New York: Praeger.

Hogan, R., Johnson, J. A., & Emler, N. P. (1978). A socioanalytic theory of moral development. In W. Damon (Ed.), New directions for child development: Vol. 2. Moral development (pp. 1-18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219780203

Piaget, J. (1997). The moral judgment of the child. (M. Gabain, Trans.). New York: Free Press Paperbacks (Original work published 1932 by Routledge, Trench, Trubner & Co.).

Riesman, D. (1961). The lonely crowd. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rubin, G. (2017). The four tendencies. New York, NY: Harmony Books.