Emotional Intelligence

Emotional Intelligence Makes Creativity Happen

A new study finds that emotional intelligence can promote creativity.

Posted February 21, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

A new paper in the Journal of Creative Behavior shows the power of emotional intelligence to make creativity happen. My colleagues and I at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence collaborated with the Faas Foundation on a survey of a representative sample of close to 15,000 people across the U.S. and found that emotionally intelligent supervisors create a climate that benefits creativity and innovation in those they work with.

What do emotionally intelligent supervisors do? First, they are skilled at reading employees’ emotions, such as realizing when someone is upset or disappointed or when they are worried about changes at work. They not only can read emotions but acknowledge them explicitly.

Second, they help employees channel their feelings toward achieving important goals. They inspire enthusiasm and they model decision making that takes into account both optimistic and pessimistic voices (and concerns and hopes behind them).

Third, emotionally intelligent supervisors understand how different decisions or events affect people’s experiences at work. And finally, they are able to successfully manage their own emotions, as well as help employees when they are upset or frustrated.

Our just-published Yale study asked three groups of questions. One group of questions asked people to describe their supervisors’ behavior. For example, how often does their supervisor notice if someone is feeling upset about a work decision? How often does their supervisor generate enthusiasm to motivate others?

Another group of questions asked about people’s emotional experiences of work. We asked them to describe how they typically feel about their work in their own words, and also asked them how often they experience a long list of specific emotions, from feeling content, respected, and proud to feeling frustrated, angry, or discouraged (and more!). Finally, we asked to what extent they have opportunities to grow and make progress at work and how often they are creative at work (e.g., contribute new ideas or original ways to achieve work goals).

The study results show that when supervisors acknowledge that employees have feelings and that these emotional experiences matter, the work climate becomes more positive and supportive. Employees described dramatically different emotional experiences if they had supervisors who acted in emotionally intelligent ways or not. The quality of relationships spilled into feelings about employees’ duties and tasks, and that, in turn, affected creativity and innovation in what they accomplished. Our study suggests that supervisors’ emotional intelligence is a job resource for their employees that helps both their wellbeing and successful performance at work.

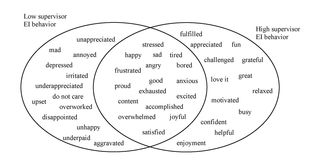

When people were asked how they feel about work in their own words, we saw that work was associated with both positive and negative emotions; people commonly experienced feeling good and proud, stressed and frustrated, tired and exhausted. Yet, two-thirds of the top feelings mentioned by those whose supervisors were emotionally intelligent were positive, while 70 percent of the top feelings mentioned by those whose supervisors were not emotionally intelligent were negative.

The details are even more interesting. Those whose supervisors were emotionally intelligent mentioned being happy three times more often than being stressed. They described feelings related to growth (e.g., being challenged, fulfilled), feeling motivated and enjoying work, and feeling appreciated. Research in the psychology of work and organizational behavior shows that these feelings create the kind of environment that is conducive to optimal engagement and flourishing.

By contrast, those whose supervisors do not show emotional intelligence most often said they were frustrated and stressed. These employees reported becoming angry—they said they are irritated, aggravated, annoyed, and mad. On top of that, they were also feeling underappreciated or unappreciated altogether.

How do supervisors and leaders make a difference for their employees’ ability to be creative? Organizational behavior scholars Jing Zhou and Jennifer George have shown that emotionally intelligent supervisors know that emotions provide information about ourselves, the environment, and those around us. Emotionally intelligent supervisors are able to notice employee dissatisfaction, recognize that dissatisfaction conveys information about a real problem, and can find a way to approach this problem as an opportunity for improvement. Emotionally intelligent supervisors can manage their own and employees’ emotions to help with creative work. They can recognize when people are overly optimistic and can provide informative feedback to prevent settling on ideas prematurely and inspire persistence.

The Yale study shows that supervisors can create a climate where employees have opportunities to grow and are inspired and motivated in their jobs. Supervisors who acknowledge that employees cannot leave emotions at the door, who recognize employees’ feelings, understand where they are coming from, and who help employees manage their feelings, will have both happier and more creative employees. The results are relevant for anyone who influences others, such as teachers working with students or parents with their children. The emotional climate we create will influence both how those around us feel and what they are able to do.