Unconscious

Consciousness and Its Three Stages of Processing

Part 1: Processes preceding the construction of the “conscious field."

Updated August 1, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

In a few months, this blog will turn 15 years of age. How time flies when one is thinking about consciousness and the brain! I think the 15-year mark is a good point at which to write a series of posts that synthesize many of the conclusions (including new ideas) that we have discussed regarding consciousness and the brain. I have concluded that a useful way in which to divide up the conclusions is to present them in terms of three stages of processing in the brain: Stage 1: Unconscious processes preceding, and giving rise to, the construction of the “conscious field”; Stage 2: The conscious field; and Stage 3: Unconscious processes following, and reacting to, the conscious field. These three stages are qualitatively different from each other, and each has unique properties and principles of operation.

Before we continue, I should clarify some terms that we used in the foregoing. The term “conscious field” refers to everything that one is conscious of at one moment in time. Each thing one is conscious of is called a “conscious content.” For example, right now, my conscious field is composed of several conscious contents, including the sight of my computer screen, the sound of birds outside, the smell of coffee, the urge to straighten my posture, and the memory that I must turn off the coffee maker before it burns my coffee.

For today’s post, we will discuss only Stage 1 and focus on its phenomena and principles of operation that reveal fascinating things about consciousness and the brain.

Stage 1: Unconscious Processes Preceding, and Giving Rise to, the Construction of the Conscious Field

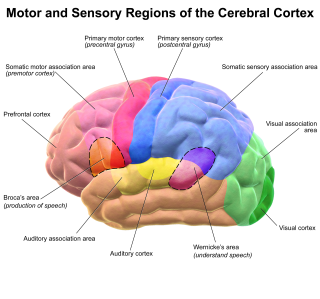

The conscious field emerges from neural activities (see related blog here) of which we are unaware, just as one is not directly aware of the machinery in a television that gives rise to the images on the screen. One is aware of the movie and unaware of all the processes going on, involving many diodes and transistors, to instantiate that movie. In Stage 1, the processes include phenomena such as inter-sensory processing and “top-down processing” (also called “knowledge-based processing”). These are phenomena that determine what we experience consciously, but their workings are opaque to one (they are “cognitively impenetrable,” to use the term by Zenon Pylyshyn).

We will first review inter-sensory processing. In this form of processing, what is perceived in one sense (e.g., vision) can be influenced by what is perceived in another sense (e.g., audition). Inter-sensory illusions are a dramatic case of inter-sensory processing. For example, in the McGurk effect (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976), an inter-sensory illusion involving vision and audition, an observer views a speaker mouthing the phoneme “ga” but is presented with the auditory stimulus “ba.” Surprisingly, as a result of the sensory discrepancy, the observer perceives “da.” The observer is unaware of any discrepancy and is aware only of its perceptual product (“da”). Click here for a demonstration of this effect.

There are scores of these inter-sensory illusions, involving all the sensory modalities and including the famous “ventriloquism” effect, in which the source of a sound is attributed to a spatial location in which there is motion. One is conscious of the illusory percepts created by these inter-sensory processes, but is unaware of the processes that lead to these illusory percepts.

In top-down processing, knowledge influences how one perceives a stimulus. One is unaware of the mechanisms that lead to this influence. For example, in the Warren phonemic restoration effect (Warren, 1970), a subject in an experiment hears the word “construction” but the word is interrupted and split in half by a cough in this way: “CONST — cough — TION.” Even though the entire word “construction” was not presented auditorily, the subject perceives the complete word. There are scores of effects that stem from such top-down, knowledge-based processing. One of the most peculiar and dramatic is that of “phantom words.” (Click here for a demonstration.)

For this post, I focused on inter-sensory processing and top-down effects because they dramatically reveal that we are unaware of the mechanisms involved in the construction of the conscious contents. But they are not the only unconscious mechanisms in Stage 1. In addition to inter-sensory processes and top-down processes, there are other kinds of processes (e.g., contrast effects, context effects, perceptual priming and semantic priming) that are unconscious and influence what we end up experiencing consciously. In addition, during Stage 1, there are processes outside of perceptuo-semantic analysis that are unconscious and influence which conscious contents we experience. For example, there are certain forms of automatic memory retrieval, of attentional processing (e.g., the involuntary, “attentional capture”), of syntactic/linguistic analysis, and of emotional processing (e.g., the initial “appraisal” of a stimulus as dangerous or not dangerous). (Click here for post on the encapsulation of emotional processes.) ("Corollary-discharge" from motor centers, too, can influence the nature of the conscious contents we experience, as is obvious in the case of vision.) For our purposes, a review of the nature of inter-sensory processing and top-down effects is sufficient to appreciate that, before the conscious field is instantiated, complex processes that are unconscious take part in its construction. (For the interested reader, there are many other sophisticated mechanisms of which one is unaware in Stage 1, including the mechanisms underlying color constancy, sound localization, Reichert Detectors [for motion perception], Gestalt principles of perception, and how indirect sounds are “cancelled out” in auditory perception.)

These unconscious processes, which Helmholtz called “unconscious inferences,” are sophisticated and intelligent. They usually benefit sensory analysis, and the behavior that depends on it, by providing a more intelligent interpretation of the stimulus out there (Merker, 2012). For example, in the McGurk effect, a given conscious content (“da”) emerges from polysensory configurations of afference, leading to the “global best estimate” (Merker, 2012) of what that content should be (Helmholtz 1856/1961). In some cases, these unconscious inferences give rise to entertaining illusions, but that is not what they are normally there for. They normally provide a richer, and more vetted, interpretation of the stimulus out there (“the global best estimate”; Merker, 2012). For example, the well-known illusion of “Mach bands” is responsible for “edge enhancement” in object and scene perception.

In light of the foregoing, it is not surprising that a recurrent conclusion in the history of psychology and neuroscience is that one is conscious of the outputs of these intelligent processes but is not conscious of the processes themselves. These conclusions were reached by figures such as Karl Lashley, Roger Shepard, and George Miller, among others. I should add that nothing mentioned in this particular post is controversial; most of these phenomena are widely known in cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

Some theorists refer to Stage 1 as "pre-conscious," but I am avoiding the term only because it means different things in different subfields. For example, in psychoanalysis, it means something that one is unconscious of but that one can become conscious of. The processes we discussed concerning Stage 1 are "cognitively impenetrable," and one cannot be conscious of them.

Once the processes of Stage 1 are complete, then we are ready for Stage 2 (The Conscious Field), which is the topic of our next post.

References

Helmholtz, H. von (1856/1961). Treatise of physiological optics: Concerning the perceptions in general. In T. Shipley (Ed.), Classics in psychology (pp. 79–127). Philosophy Library. (Original work published in 1856).

McGurk, H., & MacDonald, J. (1976). Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature, 264, 746 – 748.

Merker, B. (2012). From probabilities to percepts: A subcortical “global best estimate buffer” as locus of phenomenal experience. In E. Shimon, F. Tomer, & Neta, Z. (Eds.), Being in time: Dynamical models of phenomenal experience (pp. 37 – 80). Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Warren, R. M. (1970). Perceptual restoration of missing speech sounds. Science, 167, 392–393.