Creativity

How Arguments Solve Problems

Come, let us reason together. (Part 2)

Posted September 26, 2018

Arguments often create bad feelings and lead to fights. So why do we engage in them? Adam Grant suggests that good arguments help us solve problems, and solve them more creatively:

"If no one ever argues, you’re not likely to give up on old ways of doing things, let alone try new ones. Disagreement is the antidote to groupthink. We’re at our most imaginative when we’re out of sync."

And we should grant (heh) Grant's point. Creativity is indeed one of the upsides of arguments. But we should also note Grant's main caveat: arguments work best when relationships are secure (a point I harped on here).

In this post I wish to point out a couple more ways arguments help us solve problems, namely, they help us expand common ground and refine our differences. And in the process I also want to extend the "reason as a dance" metaphor/model we started to develop in part one of this series.

Consider this exchange between Michael and Serenity.

Michael: We should throw a party next weekend.

Serenity: We should have a party, but not next weekend, and I'm too busy to help regardless.

Michael: Oh yeah, next weekend doesn't work. But why can't you help? It's too much work for one person, and you never help.

Serenity: You're right. I almost never help, but you're good at it, and my work is super important right now.

Michael: I am good at it, but it's still too much work for one person.

[a sobbing, bleeding child enters the room]

With the entry of the child, the argument has been interrupted by more important matters. And that gives us a chance to take stock of where things stand.

In part one of this series we learned to see reasoning as a series of acts, frowns, points, and nods. And we can see that Michael and Serenity are, indeed, doing a lot of acting, frowning, pointing, and nodding (though, as with many arguments, many of the frowns are concealed, being bundled up with pointings to create a point/counterpoint dynamic).

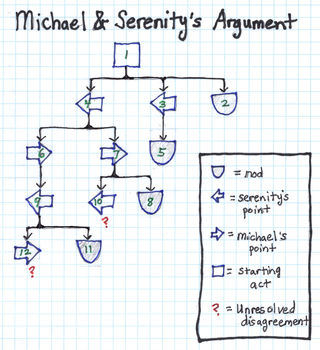

Here is a diagram of the moves in dance so far:

The numbers in the diagram correspond to the main moves in the argument enumerated below:

M: (1) We should throw a party next weekend.

S: (2) We should have a party, (3) but not next weekend, and (4) I'm too busy to help regardless.

M: (5) Oh yeah, next weekend doesn't work. But why can't you help? (6) It's too much work for one person, and (7) you never help.

S: (8) You're right. I almost never help, but (9) you're good at it, and (10) my work is super important right now.

M: (11) I am good at it, but (12) it's still too much work for one person.

There are many things to note about this argument that also apply to arguments in general.

First, nods are terminal while frowns and counterpoints keep the argument going. Without some disagreement we will see neither the upsides nor the downsides of arguments.

Second, when someone makes multiple points at once, or evaluates their partner's point in multiple ways at once, the argument branches. Some branching makes an argument interesting. Too much branching can make an argument scattered and bewildering.

Third, the number of contested points can multiply, even as the argument gets closer to resolution. Michael and Serenity started with one big contested point: Serenity should/shouldn't help Michael throw a party. And now they have two more focused points to consider: (10) Serenity is too busy and (12) it's too much work for Michael to do alone.

Fourth, as the argument proceeds, these increasingly-refined points of conflict are being framed by more and more explicit common ground. Moves 2, 5, 8 and 11 all make points of common ground explicit. It's easier for Michael and Serenity to have hope of resolving the conflict, given that they share many attitudes. They both want to have a party. They both agree that next weekend doesn't work. They both agree that Serenity rarely helps. And they both agree that Michael is good at throwing parties.

In general this is how arguments tend to go between friends. Even when bad feelings surface, and even when points of disagreement start branching like heads of a hydra, important kinds of progress are being made. We are expanding explicit common ground and getting closer to the crux(es) of the matter.

Grant's Caveat

Grant's main caveat applies not only to creativity, but also to the expansion of common ground and refinement of differences. The benefits stop flowing when the participants stop feeling secure.

Where things go from here depends on Michael and Serenity, on their moods, their goals, their hopes and fears, their speech craft skills, and so forth.

If Michael is frustrated and impulsive and wants above all to get Serenity's help throwing the party, he might try (and perhaps also later regret) a sarcastic continuation. Even with their bleeding child yet untended, he might say to the child, but aimed also at Serenity:

"Daddy will help you, Mommy is too busy with her very important work right now."

Ouch.

Perhaps Michael imagines that these words will cause Serenity to feel guilty for prioritizing work over the needs of her family, and she will make some useful inferences in her own mind while he is away tending to their child. This might work out the way he imagines, but likely not. It's more likely that Serenity will feel attacked and will feel like Michael is not trying very hard to understand where she is coming from. And she will resent the fact that he is using their sobbing, bleeding child as a pawn in his game.

And the benefits of the argument will stop flowing.

As an alternative, Michael might pursue a more diplomatic continuation instead. After their child's needs are met, he might resume the argument by consolidating common ground and working toward a solution that works for everyone:

"OK, so we both want to have a party, and it looks like the weekend after next is a good time to have it, and you have a lot on your plate, and I'm the one who knows best how to throw parties. So what if I scale back my expectations a bit, and find ways for you to help that fit your existing schedule?"

This would be a more cooperative continuation, and it could just as easily be Serenity who suggests this resolution.

Or maybe Michael wants to throw a grand party and doesn't want to compromise like this. In that case he might pick up right where the argument left off and keep whittling away at the points of disagreement. They can explore together just how busy Serenity is, and they can explore together how much Michael might be able to accomplish on his own.

A million other continuations are possible. And a million other continuations can be productive, as long as both parties remain secure.