Motivation

The Hero’s Journey: Finding Therapy That Fits

The importance of finding a therapist and therapy that fits for you.

Posted June 13, 2019

In a comment on a prior post on What Doesn’t Work in Psychotherapy, one reader, Mille, made this great comment:

“I went to a therapist that was well qualified and good reviews, but I found there was no real connection. After three sessions I found another, still not working with that one either. As frustrating as it was, I found a psychologist that I could feel comfortable with. It was worth the search! Therapists aren't appliances, they are people with personalities, there has to be chemistry like any relationship. And therapy takes work and commitment. The therapist shouldn't be doing all the heavy lifting.”

This is so true!

In some earlier posts on When our Solutions Become the Problem, and Nine Dots: A Key to Psychological Problems, I discussed how we get trapped in what we know for sure and our vicious cycle solutions that build our problems. To step out of our proverbial problem boxes is always counter-intuitive, anxiety provoking, and often even threatening. To do so it is most helpful to have someone such as a counselor or therapist outside our everyday life to serve as a trusted guide. Finding someone who fits, as did Mille, is often a process or journey.

The Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell, the eminent scholar who wrote about cross-cultural views on religion and myths, wrote a classic book titled The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In this work, he traced a similar journey across cultures where the hero of the tale faced a dilemma that forced him or her to step out of their ordinary world to discover a new path and transformative resolutions. In most of these stories, the hero is aided by someone from outside their familiar life who offers guidance and help in their quest—the Wizard or Glinda, the good witch of the north in the Wizard of Oz, Yoda in Star Wars, the wizard, Gandalf, in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and so on. The parallel with linking with a trusted practitioner for psychotherapy is striking.

What all Effective Psychotherapies Offer

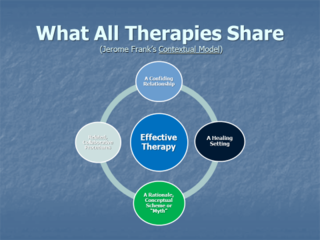

In my last post on Hope: A Foundation for all Psychotherapy that Works, I referred to the classic work of Jerome Frank, Persuasion and Healing (Frank & Frank, 1991) where he made the link between demoralized clients and the impact offered by hope through psychotherapy. Frank’s work actually covered healing traditions in addition to psychotherapy and across cultures and religions, and he concluded that all helping models included the same four components:

· A Confiding Relationship with one who can understand and empathize with the one in distress

· A Healing Setting outside one’s typical context, like a church or a therapist’s office

· A Rationale, Conceptual Scheme, or “Myth” that makes sense of the dilemma and implies direction as in our discussion of hope

· And, Related Collaborative Procedures designed to resolve the current distress or dilemmas as explained and agreed upon

The Therapeutic Relationship

What we are talking about is establishing a therapeutic relationship with a trusted guide for your own hero’s journey. The APA Division of Psychotherapy convened a task force to review and comment on scientific evidence related to empirically supported relationships (Norcross, 2002). That group decided to adopt a general operational definition of the psychotherapy relationship. The core elements of the relationship were said to be:

· The alliance,

· Empathy and positive regard and

· Goal consensus and congruence.

But what do these mean?

The Alliance in Good Psychotherapy

In many ways, the therapeutic or working alliance is used almost interchangeably with the term relationship. (Horvath and Bedi, 2002) include the following elements in describing a good working alliance:

(1) The alliance refers to the quality and strength of the client-therapist relationship

(2) This includes positive bonds such as mutual trust, liking, respect, and caring

(3) It also includes cognitive components of the relationship including consensus about and commitment to the goals of therapy, and to the means or tasks of therapy by which these goals may be attained

(4) It involves a partnership where all parties are actively committed to their roles in the process of therapy and belief that all others are also enthusiastically engaged in the same process, and

(5) The alliance is a conscious and purposeful aspect of the relationship where all parties can describe the quality of the alliance and that there is a therapist or helper committed to providing assistance to the client or clients

This is often boiled down to what is depicted in the below diagram, of Positive Bonds, Collaborative Goals, and Collaborative Tasks. But, who determines the quality of empathy and working alliance and the fit of rationales and consequent therapeutic tasks—therapists, observers, or clients?

The Hero Defines the Fit

A range of studies from the psychotherapy literature has found that therapists are the worst at evaluating the strength of their relationships with clients. Clients are best at evaluating positive alliances and working relationships with therapists—and when their evaluations are positive, so are the prospects of good results in psychotherapy.[1]

Flexibility & Fit

You can see that effective psychotherapy is all about helping us step outside of our problem-generating worlds and our solution-generated problems. Not only is this challenging for clients, but it may also be confusing, counter-intuitive, paradoxical, and anxiety provoking if not downright frightening.

To make this pattern shift or reversal in the flow of their life and in the direction of their goals, clients need to have faith in their therapist. Therapists promote faith by showing they understand the client’s problems. Therapists validate clients’ distress because they understand the context for it. Finally, they inspire hope by offering a therapeutic rationale that makes sense. This helps the client to see the therapist as skilled and capable of successfully guiding them on their journey. A key element in this formula is fit.[2]

The Journey

The best thing for Mille at the beginning of this post is that she continued to follow her hero’s journey to find a fit with the best therapist or guide. In a following post, I’ll address the importance of rationale, or what Frank has called a “myth”, to the idea of flexibility and fit in psychotherapy that works.

[1] Adapted from Fraser, J. S. & Solovey, A. D. (2007). Second-order change in psychotherapy: The golden thread that unifies effective treatments. Washington, DC: APA Books.

[2] Adapted from Fraser, J. S. (2018). Unifying effective psychotherapies: Tracing the process of change. Washington, DC: APA Books.

References

Frank, J. D. & Frank, J. B. (1991). Persuasion and healing. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press.

Horvath, A. O, & Bedi, R. P. (2002). The alliance. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that Work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp.37-69). New York: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C. (2002). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York: Oxford University Press.