Stress

Take Control of Your Stress and Burnout

To beat burnout and reduce stress, you must make a plan.

Posted August 7, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Burnout is an unmitigated chronic stress induced condition.

- Stress and burnout do not go away on their own.

- To eliminate stress and burnout you must take control and make plans.

- The plan and process do not have to be complicated.

I have written quite a few posts for Psychology Today about stress and burnout (See my posts). I am frequently asked what is the single most important action I can take to address burnout and its underlying stressors. Although stress reactivity is tremendously complicated, involving intricate neurotransmitter, hormone, and immune system interactions, coupled with psychological underpinnings such as developmental issues, schemas, perception, prior operant conditioning, habituated patterns, neural pathways, and memory storage and retrieval, the answer to the question is quite simple: Actively take control of your stress that causes burnout!

Burnout is caused by longitudinal, unmitigated, chronic stress (Comer, 2020). Mitigating it requires a unique plan: You must manage it. Stress and burnout do not vanquish on their own. In fact, chronic stress is well reported to lead to many pathologies, both physiologically and psychologically (Comer, 2020).

When does the stressor occur?

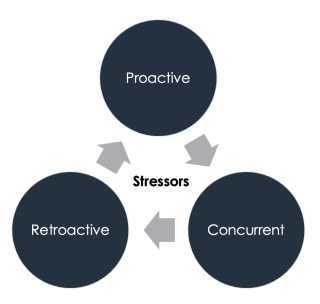

To create a successful plan, you must first think about the underlying causal factors leading to chronic stress-induced burnout from three temporal aspects: proactive, concurrent, and retroactive (see Figure 1).

Proactive — this entails taking steps to prevent stress from ever occurring.

Concurrent — this means learning to handle stress when it actually occurs, in the moment.

Retroactive — this involves evaluating your stress after it has occurred and defining ways to address and release it.

Considering these three time-based aspects of stress can be helpful for learning more about your unique stressors.

For example, my doctoral dissertation was on post traumatic stress in veterans (Comer, 2020). A veteran may have been diagnosed with PTS, which is the retroactive component of stress — that is, the trauma producing stressors have already occurred and plans to address them must be retroactively applied to reduce the symptoms of an event that cannot be changed. This is by far the most difficult way to deal with stress.

On the other hand an active duty service member may be going through actual combat in the moment. This requires concurrent stress management — using techniques to mitigate the active occurrence to stress reactivity to be able to continue functioning optimally (i.e., not succumbing to flight or fright psychophysiolocial responses, which can prove devastating during actual emergent stressors).

Finally, when a young man or woman enters military service, there is a tremendous opportunity to train the person in advance of ever entering combat so that he/she is prepared to handle stress more effectively when is occurs. This is a proactive plan and is what most military training is based on. It is by far the best time to deal with stress because it has not yet even occurred.

These concepts do not have to be in the sole purview of military operations. They can be applied to any aspect of your life where stressors are present.

The second step is making a plan

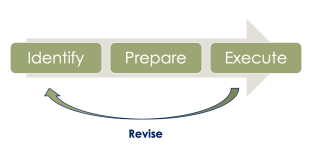

Once you have determined when the stressor will occur, is occurring, or has occurred, you can think about creating your strategy for dealing with it. An easy and effective method is to Identify, Prepare, Execute, and Review (see figure 2).

Identify — Identify the stressor that leads to dysregulated behavior. For example, perhaps you struggle with a rude co-worker who frequently upsets you. Simply identifying and acknowledging the stressor can be therapeutic itself.

Prepare — this is when you plan specific actions to mitigate the effects of the stressor. In this case, how can you take steps to address the rudeness of the co-worker? For example, you can walk the other way when you see the person, or tell the person that you are busy working on a project, or maybe you want to address the person's rudeness directly and explain how it makes you feel.

The options are endless. But the key is that you are taking active control of what you can — building upon the concept of an internal locus of control.

Execute — the best laid plans are completely useless if you do not implement them. Take your action plan and apply it the next time the stressor presents itself. This furthers your sense of control and active engagement.

Revise — finally, review your action(s) and determine the level of effectiveness. Make revisions as necessary.

By following this simple process, you will find relief just from the fact that you are trying to exercise control of your stress. Hopefully, you will also find an action that works! And make sure that you positively reinforce yourself by acknowledging the fact that you took action to improve a difficult situation and did not allow stressors causing chronic stress and burnout to roll over you.

References

Comer, W.J. (2020). Mindfulness-based treatments for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic literature review. Doctoral Dissertation. California Southern University, Costa Mesa, CA