Neuroplasticity

Has Lockdown Life Evoked the Sensation of Jamais Vu?

Could brain changes during isolation make common experiences feel less familiar?

Posted June 20, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

After two years of lockdown, a number of conferences and conventions resumed holding live meetings this year. These afforded the attendees with opportunities to reconnect in person and spend time with friends, colleagues, and fellow professionals. Throughout one convention this spring, I kept hearing people comment on how easily they fell into the same rhythms with others and yet how paradoxically odd it all felt, both familiar and unfamiliar. Special effects wizard Fon Davis, whose experience includes working on The Nightmare Before Christmas and various Star Wars films, wondered why this might be, and he suggested that neurological changes that had developed over the previous two years might account for some of that. It's a smart question.

Experience has been shown to alter neural pathways. We often think of neuroplasticity as the brain's ability to "rewire" itself after injury (Sebastianelli et al., 2017) as new connections form and uninjured parts may begin to take over functions previously performed by those now injured. What is injury, though? Would two years of neglect and reduced activity in certain areas due to lockdown and social isolation count as injury in this sense? Even without injury, could it be that the areas experiencing reduced activity change in other ways during that time - for example, by reassigning some neurons to whatever new routines began to replace old ones? In that case, returning to a previous situation might activate the connections that remain in place while failing to activate synapses that have been reassigned, so to speak.

Thinking of neuroplasticity as "the brain’s capacity to continue growing and evolving in response to life experiences" regardless of injury may be more useful as well as more objective. The brain may also activate conflicting patterns, elements of both old experience and new.

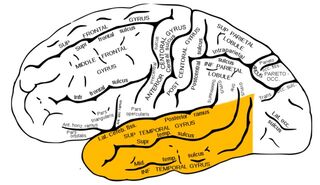

Could such neuroplasticity account for the intense feelings of alienness that people sometimes experience upon returning to old routines and situations? As opposed to the better-known phenomenon déjà vu ("seen before"), in which a situation feels strangely familiar even though it should not, jamais vu ("never seen") arises when something we know to be familiar seems subjectively unfamiliar. It feels "off." This seems to occur about a tenth as often as déjà vu does and in one third as many people. Both occur more frequently among individuals who have suffered epileptic seizures, particularly those associated with temporal lobe epilepsy (Illman et al., 2012; Ko & Kuo, 2018; Kusumi et al, 2006; Sengoku et al., 1997). Both experiences change in frequency with age (Brown & Croft, 2011; Walker-Journey, 2022), growing less common, but it is not known whether that happens because of age-related deficits with age or simply because experience, learning, and crystallized intelligence normally increase. Brain changes tend to get studied after the fact most of the time, limiting researcher's ability to examine the causes of certain phenomena.

Scholars struggle to explain both, especially jamais vu (Findler, 1998; Ko & Kuo, 2018). Not only is jamais vu the less common phenomenon, it is also more difficult to manipulate experimentally. Researchers can manipulate configurations of environmental stimuli (Cleary et al, 2012) as well as the number and types of cues to see how much a familiar scene can be altered before a viewer knows the scene looks familiar without having enough information to recognize why, and this seems to be one of the main reasons that the sensation of déjà vu occurs as recognition without identification (Catling et al, 2021; Cleary & Reyes, 2009; Ryals, 2013).

When environmental cues resemble a previous setting just enough to make it feel familiar even though the person has never been there, a false positive recognition has occurred. When the familiar evokes a sense of unfamiliarity, a false negative recognition has occurred. The false positive may be easier to study because it is easier to test why something occurred than why something did not - akin to how we cannot prove the null hypothesis.

One more thing plays a role in why two years of lockdown may have caused familiar experiences to seem "off": Because they are. Differences both little and large have changed our circumstances. The world is still different in many ways. A setting or situation you visit for the first time in two or three years - say, a family reunion - mixes the sensations of familiarity and unfamiliarity. A family reunion in 2022 cannot exactly match what the reunion was like in 2019 because everyone who's there is three years older instead of the usual one year. If the event carries on as though lockdown never happened, with everyone hugging easily and no one wearing masks, it carries a tinge of new strangeness because it differs from the new norms that developed throughout COVID-19 lockdown.

In The Nightmare Before Christmas, the aforementioned Tim Burton film that Davis worked on, protagonist Jack Skellington impersonates Santa Claus when he wants to experience the fun and joy of Christmas gift-giving. Children throughout the world find the fake Santa Claus to be unnerving because he gets things wrong in unsubtle ways. Jamais Vu works more subtly, which can be additionally unnerving when we do not know why the situation feels wrong and we have trouble trying to articulate our own feelings.

References

Brown, A. S., & Croft, K. (2011, November). This poster seems strangely familiar: Age changes in Deja Vu and Jamais Vu [Conference session abstract]. 52nd Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Seattle, Washington. https://doi.org/10.1037/e520602012-668

Findler, N. V. (1998). A model-based theory for déjà vu and related psychological phenomena. Computers in Human Behavior, 14(2), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(98)00007-7

Illman, N. A., Butler, C. R., Souchay, C., & Moulin, C. J. (2012). Déjà experiences in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research & Treatment, 2012, 539567. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/539567

Ko, K. L, & Kuo, C.-H. (2018). Surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. In R. G. Ellenbogen, L. N. Sekhar, & N. D. Kitchen (Eds.), Principles of neurological surgery (4th ed., pp. 761-770). Elsevier.

Kusumi, T., Fukao, K., Murai, T., Yamada, M., & Sengoku, A. (2006, November). Deja vu and jamais vu in normal and epilepsy patients [Conference session abstract]. 47th Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society, November 16-19. https://doi.org/10.1037/e527352012-745

Moulin, C. J. A., Bell, N., Turunen, M., Baharin, A., & O'Connor, A. R. (2020). The the the the induction of jamais vu in the laboratory: Word alienation and semantic satiation. Memory. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1727519

Sno, H. N. (2000). Déjà vu and jamais vu. In G. E. Berrios & J. R. Hodges (Eds.), Memory disorders in psychiatric practice (pp. 338–347). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511530197.016

Read, J. D. (1991). Knowing who's new: from déjà to jamais vu. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 32(4), 647–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0084649

Read, J. D., Vokey, J. R., & Davidson, M. (1991). Knowing who's new: The phenomenon of Jamais Vu [Conference session abstract]. 32nd Annual Meeting The Psychonomic Society, San Francisco. https://doi.org/10.1037/e665402011-140

Sebastianelli, L., Saltuari, L., & Nardone, R. (2017). How the brain can rewire itself after an injury: The lesson from hemispherectomy. Neural Regeneration Research, 12(9), 1426–1427. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.215247

Sengoku, A., Toichi, M., & Murai, T. (1997) Dreamy states and psychoses in temporal lobe epilepsy: Mediating role of affect. Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 51(1), 23–26. https://doi:DOI 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02361.x

Walker-Journey, J. (2022, January 27). Jamais vu is not déjà uu. It's quite the opposite. Science. https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/inside-the-mind/human-brain/jama…

Cleary, A. M., & Reyes, N. L. (2009). Scene recognition without identification. Acta Psychologica, 131(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2009.02.006

Catling, J. C., Pymont, C., Johnston, R. A., Elsherif, M. M., Clark, R., & Kendall, E. (2021). Age of acquisition effects in recognition without identification tasks. Memory. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2021.1931695

Ryals, A. J. (2013). Isolating partial recollection as a distinct entity in recognition memory using a modified recognition without identification (RWI) paradigm. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 74(1-B(E)).

Cleary, A. M., Brown, A. S., Sawyer, B. D., Nomi, J. S., Ajoku, A. C., & Ryals, A. J. (2012). Familiarity from the configuration of objects in 3-dimensional space and its relation to déjà vu: A virtual reality investigation. Consciousness & Cognition: An International Journal, 21(2), 969–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2011.12.010