Leadership

Is Restorative Justice Exhausting?

A counter-narrative to the Sunday New York Times

Posted September 11, 2016

There has long been a perception that restorative practices—a term used to describe a variety of different approaches to "doing justice" and working through conflict that focus on repairing harm and addressing underlying needs rather than identifying and punishing the "wrongdoer"—are time consuming and exhausting. No doubt that narrative was further reinforced by the New York Times Sept. 11th online story on restorative justice in city high schools (the print version appears in today's Sunday magazine).

But is it true? Is exhaustion really a necessary "side-effect" of responding restoratively, rather than punitively, to school conflicts and harms?

I don't want to minimize the reality that walking toward conflict restoratively takes time and energy (it definitely does!) but time and energy expenditure do not necessarily result in exhaustion. Sometimes they can invigorate, not drain, and I have seen many school personnel feel energized by the shift to restorative practices.

In fact, there are at least five reasons to believe restorative practices are probably much LESS tiring than Zero Tolerance policies or even just conventional punitive discipline.

1. It's the suppression of conflicts that's tiring, not the conflicts

Many of the teachers in Leadership High School were hesitant to engage in what they perceived to be risky and vulnerable dialogue about race and racism. This is hardly surprising. We're socialized to believe that conflict (especially racial conflict) is dangerous, something to avoid or smooth over or "keep under a lid" some other way. But putting a lid on conflict is not unlike putting a lid on a full pot. Eventually, the pressure builds up and then things get REALLY messy. Cleaning up a big mess is indeed tiring, but it's not the conflict that is dangerous and messy; it's the suppression of conflict. Most conflicts start small and only build up if they are not addressed. Working through those small conflicts is like wiping a small spill with a good paper towel—far from dangerous and hardly exhausting.

In many (probably most!) schools and workplaces, racial tension and resentment have been building for years. As a result, creating a container to talk about the things we usually "reveal only to ourselves, and that in secret," does indeed take both time and emotional vulnerability. But even then, the exhaustion seems more the byproduct of anxious anticipation than actual engagement. The Times reported that those involved in the race circles at Leadership experienced more authentic connection with their colleagues. That's not draining. It's what we all wish we could have.

2. It's the acts of harm, not the restorative responses

Anyone who has been in a school in February can see that the teachers and staff are tired. In restorative schools, it might be tempting to conclude that the fatigue is due to the demands of engaging in restorative practices. I doubt it. Teachers in schools that are still doing punitive discipline are exhausted this time of year too, particularly in schools where violence and others acts of harm are frequent and unabating. It's not the restorative responses to such acts that are tiring; It's the conflicts and acts of harm themselves. In extreme circumstances (some schools qualify), just being around chronic violence can be diagnostically traumatic, as evidenced by PTSD symptoms. In circumstances less extreme, it is merely exhausting. Of course, school personnel are often tired but let's not confuse the cause with the response.

3. It's the inertia that's tiring, not the move toward restorative practices

Movement is invigorating. Inertia is exhausting. Sure, all of us would be glad to take an occasional day off to recharge, especially in February, but most teachers and school staff enjoy their work. Most are also willing to work hard, as long as they see their efforts making a difference, but few things are more exhausting than energy expenditure that doesn't produce movement or having to do something again because it didn't work the first time. This is relevant because we now have lots of compelling data that Zero Tolerance or even just the act of suspending students doesn't actually work in terms of either changing the behavior of those who were suspended or creating more safety or better learning environment for everyone else. While it is fair to say that the jury is still out on the effectiveness of school-based restorative programs, the early studies (see, for example, here and here) are promising. Now doesn't that make you want to go the extra mile?

4. It's incongruence that's tiring, not restorative practices

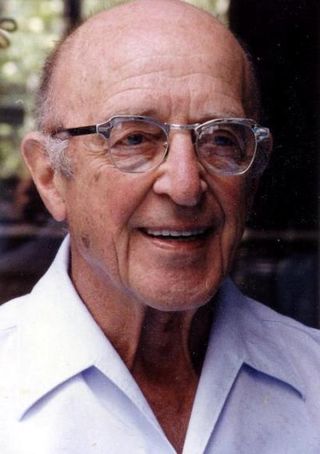

Here's the paragraph describing Randy Spotts, the head dean featured in the Times article, and how he was first introduced to restorative practices.

Even before Santos and Dunlevy arrived, Leadership [High School] had deans to whom students turned for emotional support, including Randy Spotts, who has been at the school since 1995. In 1970, Spotts was one of a few black students who enrolled at a West Virginia elementary school that had desegregated a year earlier. His grandmother frequently reproached his school’s administrators for the unequal treatment of black students. When Santos first spoke to Spotts of “the educational violence” experienced by students who are pushed out of schools through suspensions, Spotts immediately understood. For years, one of his primary responsibilities was suspending students. “My personality had always been more restorative,” Spotts says, “but my practice, because of the models that I was inducted into, were not.”

For someone like Spotts (and it should be noted that there are many Spotts in every school!), restorative approaches are often experienced as a sort of "coming home"—a new way of doing work that is more congruent with one's values and way of being in the world. For someone like Spotts, the shift to restorative practices may still be challenging but the frustration is more likely to be due to impatience with the pace of transition or perceived resistance from colleagues than with the process itself.

No one thought to ask him, but I doubt that Spotts is exhausted by the school's transition. To the contrary, the need to constantly rationalize (to one's own conscience) actions incongruent with one's values, typically takes a heavy emotional toll. But it's not just those with "restorative personalities" who are vulnerable. Every person with enough integrity to acknowledge (even if only to the self) that suspensions and other punitive discipline methods are not only ineffective (see #3) but also racially biased has to deal with the cognitive dissonance associated with regularly engaging in behaviors they know to be ineffective, if not outright counterproductive. A recent meta-analytic review published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology suggest that such "emotional dissonance may be added to the growing list of job stressors that lead to emotional exhaustion" (Kenworthy, Fay, Frame, & Petree, 2014). In short, it is the incongruence that is exhausting, not the restorative practice.

5. It's the lack of infrastructure that's tiring, not lack of energy or desire

It is commonplace (from what I have seen) for schools to try to transition to restorative practices by taking the considerable punitive infrastructure (including the human resources) and retrofit that infrastructure to do restorative justice. Thus, just as in Leadership High, it is not unusual for the deans (the personnel formerly in charge of punitive discipline) to be given the task of implementing restorative justice, often with little training and even less "buy in". For some individuals, like Spotts, the change in responsibility brings them more into congruence with their own values, but for many others, the shift to "restorative discipline" is actually NOT congruent with their values and beliefs. The result is often something that is labeled as "restorative" but is actually punitive action in disguise. While I don't know of any studies that have examined this particular phenomenon, I worry that, because they set up false expectations, such so-called "restorative" responses may be even more harmful than conventional discipline ever was. [Update 9-19-2016: I was informed that there has been at least one such study: a dissertation by Kristen Elaine Reimer examining student experiences of social control and social engagement in Scotland and Canada.

It is no doubt tiring (and probably discouraging) to have to do a job without an infrastructure in place to support it. Such an infrastructure would ideally include a designated time and space for Circles and other restorative practices, as well as the presence of school personnel and student facilitators who not only embrace a restorative philosophy but have also acquired adequate experience to support others in repairing harm and making things right.

In short, the Times notwithstanding, there is nothing inherently exhausting about restorative justice work. We just have to design and establish an infrastructure that supports it.

__________________________________________

For more racial analysis of news and popular culture, join the | Between The Lines | Facebook page and follow Mikhail on Twitter.

[Creative Commons License] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.