Addiction

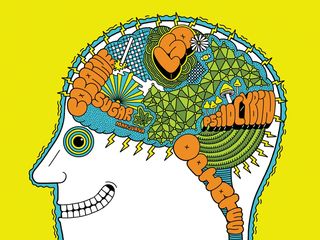

This Is Your Brain on Drugs

The neurological effects of addiction

Posted June 18, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Addiction is a disease that affects millions of Americans. It is extremely widespread, with an estimated 8 percent to 10 percent of individuals in the United States 12 years of age or older (between 20 to 22 million people) addicted to at least one substance. The human costs of this problem are incalculable. The annual financial costs, meanwhile, are estimated to be close to $700 billion due to losses in productivity, crime, and additional health care costs associated with addiction.

Just because an individual has a few drinks or very occasionally consumes illicit drugs does not mean that they have a problem with addiction. Furthermore, just because an individual may struggle with the responsible use of a drug like alcohol does not mean they have been overcome by addiction.

Addiction is distinct from substance-use disorder, which is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as being the recurrent use of drugs or alcohol resulting in clinically and functionally significant impairment. Such impairment can negatively impact one’s health, social networks, and the ability to perform functions necessary for either school or work. The disorder ranges from mild to severe. It is only when substance-use disorder becomes severe that it becomes synonymous with addiction.

In the past, addiction was considered to require a substance. In other words, one was addicted to alcohol, to nicotine, to heroin, and so on. Within this paradigm, it was believed that regular use of the substance in question eventually led to the individual’s development of both a physical dependency and a tolerance for it. The latter would lead to the need to increase the amount of the substance consumed to achieve the desired effect. The former would result in withdrawal symptoms when use was discontinued. Some of the most common substances that can produce this type of addiction include opioids, stimulants like cocaine, nicotine, and alcohol. The use of the latter two substances is, in general, more socially accepted than the use of illicit drugs, like cocaine and heroin, but they still can produce deleterious effects.

While this depiction of addiction is still largely accurate, it does not account for other types of addiction that do not involve substances. Such addictions pertain to compulsive activities. At this time, gambling is the only behavioral addiction recognized by the DSM-5, but a growing body of research suggests that other behaviors possess similar pathologies when done compulsively. These include video game-playing, binge-watching television, and having sex. Addictions of this kind may not be as physically harmful as addictions involving substances like cigarettes, alcohol, or opioids, but they can still cost lasting social and emotional damage to those caught in the web of addiction, as well as an addicted individual’s close friends and family.

Why Don’t Addicts Just Quit?

Individuals who are struggling with addiction do not simply lack the willpower to stop. The belief that one’s inability to break the cycle of addiction is due to personal shortcomings is not accurate. While inaccurate, such a belief is not irrational. Many individuals can enjoy the occasional glass of wine or weekend trip to Atlantic City without incident. From their perspective, they do not experience a strong compulsion to continue using an intoxicating substance or participating in an activity such as gambling once it has become clear that continued use is a bad idea. They can stop, and they assume that others should be able to, as well.

Individuals with addiction do not experience the world in this manner. They may earnestly wish to quit, but they cannot do so. This is not a question of willpower. Consequently, we should think of addiction not as a personal shortcoming or moral failure, but as a neurobiological issue. Certain brain functions of those who have developed an addiction become hardwired in a manner that allows the addiction to thrive. Furthermore, certain individuals are more genetically predisposed to develop addictions than others.

What Addiction Does to the Brain

Addictive drugs and behaviors activate regions in the brain that are associated with reward pathways and the pleasure center of the brain. When activated by the perceived reward, the brain releases the neurotransmitter dopamine, which causes an individual to feel good. Certain normal activities—such as when one eats, has sex, or accomplishes a difficult task—serve as rewards. They activate the brain’s pleasure center and result in the release of dopamine. Using certain drugs, such as nicotine, alcohol, opioids, or cocaine, also releases dopamine. Similarly, winning at a game of chance or doing well at a video game do, too.

Over time, dopamine ceases to be released merely due to the use of these drugs or participation in these activities (i.e., “the rewards”). Similar to how Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov noted that dogs can be conditioned to salivate once they understand that a bell indicates that dinner is about to be served, the brain becomes flooded with dopamine in anticipation of the reward, and certain external stimuli or cues tell an individual with addiction that a reward is imminent. These cues (the smell of a bar, the bright lights of the casino, seeing friends with whom one used drugs, etc.) then trigger cravings.

This kind of conditioning persists well after the drug has been flushed from the body. Consequently, a person with addiction may still be troubled by these cravings even after years of sobriety.

Certain drugs, particularly opioids and cocaine, also disrupt the brain’s reward center in a manner that is distinct from more natural rewards by preventing satiation. When one attains a natural reward, by eating a meal, for example, one’s dopamine cells eventually stop firing. Any excess dopamine within the brain’s synapses is then removed by the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Opioids and cocaine, however, release a far more potent dose of dopamine and then prevent the clearing away of excess dopamine by inhibiting the release of GABA. Opioids and cocaine effectively keep GABA from doing its job, which means that additional dopamine continues to flood the brain’s receptors.

The rush of dopamine is so rewarding that, eventually, the person with addiction becomes more focused on obtaining the dopamine release produced by the drug or activity and less focused on obtaining more natural rewards. The addiction effectively reinforces itself.

People with addiction may not even be conscious of the cues associated with their addiction. A study conducted by Anna Rose Childress, a neuroscientist based at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Studies of Addiction, found that salience attribution (which is the mental equivalent of focusing a camera on one object and leaving the remaining objects in one’s field of vision a series of blurs) is so powerful among even former addicts that they may not even be conscious of the cues. When a group of recovering cocaine addicts were shown an image of a crack pipe for just 33 milliseconds, a period of time one-tenth the length of a blink, the reward circuitry in their brains lit up. Even though they were not cognizant of seeing the pipe, the portion of the brain that activates reward pathways knew it was there.

On top of altering the reward pathways within the brain, addiction can also significantly reduce the amount of dopamine that is released either by natural rewards, drug use, or compulsory behavior. Not only do such individuals become less interested in natural rewards, but they also feel as though they need more and more of the drug or compulsory behavior to achieve the same level of euphoria as when the addiction was in its nascent state. Furthermore, on top of the severe withdrawal symptoms associated with drugs like alcohol and opioids, the absence of the desired reward leads to stress responses that result in dysphoria and anxiety. As addiction becomes more severe, the individual often becomes less concerned with experiencing euphoria than escaping the distress associated with non-use.

Addiction also alters portions of the prefrontal cortical regions—the areas of the brain responsible for overseeing executive functions like decision making and responding to exterior stimuli. This seriously impairs an individual’s capacity for regulating behavior and emotions, compounding one’s inability to follow through on making a healthy decision. Once again, this only reinforces the addiction.

Once again, addiction is a disease. It has pernicious effects on the brain, particularly neural pathways that control reward-seeking behavior. It is not a moral failing or a weakness, and it cannot be treated as such. People struggling with addiction can’t just quit, and “tough love” approaches can exacerbate feelings of social isolation and result in one’s sinking deeper into addiction.

While there are pharmacological remedies that can help to offset cravings and to make quitting easier, this is only the beginning in a long and arduous process that often requires abstaining from environments, stimuli, and individuals that can trigger cravings. Such strategies can help to curb cravings, but they are not always foolproof. The best way to overcome addiction is to not only abstain but also to restore healthy reward networks in the brain and to reestablish healthy social networks, either through familial support or a 12-step program.

To learn more about how you can help a loved one through the difficult process of recovery, you can find more information by visiting the website for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Also, you can find help in the form of a therapist on Psychology Today.

Dr. Ahmad reports no conflict of interest. He is not a speaker, advisor, or consultant and has no financial or commercial relationship with any biopharmaceutical entity whose product/device may have been mentioned in this article.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Antonio Guillem/Shutterstock