Autism

5 Tips for Using Stories in Disability Advocacy

What kinds of stories are representative, respectful and engaging?

Posted January 27, 2014

Protestors gather at the screening of an autism film

Autistic self-advocates gathered on a freezing Boston night to protest the premiere of an autism film — reportedly surprising the autism clinicians who screened it earlier this month. The clash has implications for disability advocacy across all forms of media. What do disability stories say to their various audiences? Who’s saying it? Why? How can advocates use stories less divisively and more effectively?

Looking for answers, I turned to my friend Elinor Pierce, director of ReelAbilities Boston, a disability film festival opening this week, and herself an autism film maker. See my 5 takeaways below.

Lucy Berrington As we've just seen, disability stories can lead to conflict rather than connection. The clash over this film, Sounding the Alarm, was mostly about the filmmaker, Autism Speaks, and its stubborn focus on the tragedy and pity of autism. This is a larger, long running argument over how autism should be portrayed and what that portrayal means for autistic people. What's the main lesson for advocates?

Elinor Pierce I think we have to be careful about “speaking for” the autism community. And we have to take seriously the power of narrative. That doesn’t mean we can’t tell difficult or painful stories about autism, but it’s important to ask: how does this story resonate for autistic people? It’s critical for us to engage with complex, nuanced stories, especially those that highlight agency and advocacy.

LB Autism is a vast collection of varied experiences, yet as self-advocates point out, Autism Speaks seems to recognize only one story: family devastation and grief. This is reminding me of a TED Talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the Nigerian author, on the danger of offering a single story to represent a community. It flattens the experience of those people and erodes their dignity. Have you been able to include varied perspectives in ReelAbilities Boston?

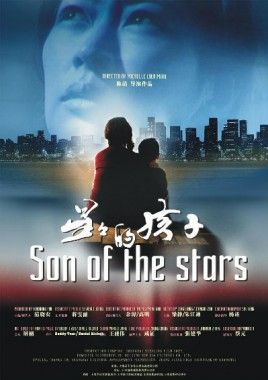

The stars of Wretches & Jabberers EP The opening film, Wretches & Jabberers, is about self-advocacy, and our first guest speakers are the protagonists, Larry Bissonnette and Tracy Thresher. We have three other films about autism. There’s a documentary short, Autism in Love, also from the perspective of an autistic adult. The feature film Son of the Stars is centered more on the parental experience, albeit in another cultural context and more extreme form. And Sensory Overload is an animated short that engages the audience in an immersive experience.

The stars of Wretches & Jabberers

EP The opening film, Wretches & Jabberers, is about self-advocacy, and our first guest speakers are the protagonists, Larry Bissonnette and Tracy Thresher. We have three other films about autism. There’s a documentary short, Autism in Love, also from the perspective of an autistic adult. The feature film Son of the Stars is centered more on the parental experience, albeit in another cultural context and more extreme form. And Sensory Overload is an animated short that engages the audience in an immersive experience.

Sensory Overload by Miguel Jiron

LB Which do you think is more powerful in advocacy: fictional narrative or documentary? How do they work differently?

EP With either form you might ask: is this really true or real? The notion that documentary represents “truth” can be problematic. It’s at risk of saying there’s one way of understanding autism and here it is. What do they leave out? Who’s telling the story on whose behalf?

With fictional narrative the story can be more emblematic than true to one person’s experience. But either form, done well, can bring two “competing” ideas into conversation — like the notion of autism based on a medical model of “disease” versus those who consider it a “different” way of being.

LB How fully do the two feature-length films in the festival, Wretches & Jabberers and Son of the Stars, represent unaccustomed points of view?

EP Wretches & Jabberers does a better job on the self-advocacy side. I like its use of captions to embed the idea that there are different ways to communicate, without privileging speech. The decision not to use voiceover is about a commitment to the protagonists’ perspectives. Son of the Stars is the parental point of view, but it includes glimpses from the child’s perspective. At any point when telling our stories we should be aware that others have their own versions that overlap with ours.

LB The stripped down message of these films is again this huge need for meaningful support and acceptance. But in both cases I found the delivery very palatable.

Neurodiverse partners in Autism in Love EP I hope that the films in the festival show that it’s possible to tell a visually compelling, emotionally engaging story about autism that doesn’t have to polarize the community. These films can still ask questions about the implications of insufficient support, services and understanding about autism. In Son of the Stars, set in China, it’s the mother’s problem to solve. We witness her acts of desperation as well as her expressions of love.

Neurodiverse partners in Autism in Love

EP I hope that the films in the festival show that it’s possible to tell a visually compelling, emotionally engaging story about autism that doesn’t have to polarize the community. These films can still ask questions about the implications of insufficient support, services and understanding about autism. In Son of the Stars, set in China, it’s the mother’s problem to solve. We witness her acts of desperation as well as her expressions of love.

LB I found that movie captivating, though the mother behaves in ways that are abhorrent. She keeps her 7-year-old son literally on a rope — and it gets worse. There are redemptive elements. But many autistic adults have had difficult relationships with their parents, and I wonder whether they will feel able to forgive this mother.

EP The mother isn’t intended to be an example of how to be an autism parent. The rope may be understood as a crude and cruel device, or as an adaptive response to protect a child. There are dimensions of her experience that are emblematic. How is the rope symbolic of the connection between a parent and child, perhaps made more complex through the experience of autism? In many respects this film is not easy to watch, yet the cinematography is beautiful. (After I watched the film, I learned that the Director of Photograpy has a child with autism.)

LB It’s amazing how many points of contact there are in raising an autistic child in two such contrasting societies as China and the U.S. For example, the mother is stunned by the unexpected kindness of a stranger towards her son. I can relate to her surprise, although not her response.

EP The “first world” version of this is the Dear Daddy letter that went viral last week [written by an autism mother who was astounded by the supportiveness of a stranger]. It was a beautiful story, yet it also shows how low is our bar, how little understanding autism parents have come to expect.

LB I understand there’s no self-advocacy movement in China yet.

EP Many countries may not have the organization and infrastructure that faciliates it. Wherever you are, parents have to advocate for their child at least until he or she can self-advocate. What does that mean in an environment in which “autism” doesn’t have a meaning?

LB That’s the case in the Somali immigrant community of Minnesota, the subject of your documentary in development, No Word for Autism. [View the short version.]

EP That film looks primarily at the advocacy efforts of Somali American mothers whose children are still young. Over the years their stories become less about finding a cure and more about equal access to quality services. I do worry about spending too much time on polemic and bifurcation, or competing narratives, when the needs of children, adults and families are very real.

5 takeaways for using stories in disability advocacy

Son of the Stars shows a family's autism experience

1 Incorporate a range of perspectives and experiences into the overall message. Include disabled individuals, their families and professionals. Represent varying races and cultural, ethnic and socioeconomic contexts.

2 Acknowledge the complexities and nuances of the experience, including the positives. These enhance rather than diminish messages about the need for understanding and support, and escape the Pity model.

3 Be clear that this is A Story, not The Story.

4 Be aware that stories and audiences can connect across different cultures and circumstances.

5 Ask people who have the disability: what are the implications of this story for you and your community?

This list is my distillation of what I've learned from advocates. How can it be improved? Please comment below.

ReelAbilities Boston is hosted by the Boston Jewish Film Festival. The founding partner is the Ruderman Family Foundation.

Protest photo by Lydia Brown at Autistic Hoya.