Fear

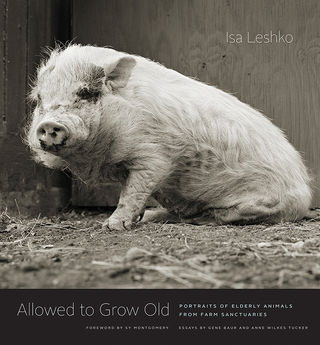

Allowed to Grow Old: Radiant Portraits of Elderly Animals

A collection of moving images portrays heart, dignity, and unique personalities.

Posted May 24, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

"There’s nothing quite like a relationship with an aged pet—a dog or cat who has been at our side for years, forming an ineffable bond. Pampered pets, however, are a rarity among animals who have been domesticated. Farm animals, for example, are usually slaughtered before their first birthday. We never stop to think about it, but the typical images we see of cows, chickens, pigs, and the like are of young animals. What would we see if they were allowed to grow old?...Open this book to any page. Meet Teresa, a thirteen-year-old Yorkshire Pig, or Melvin, an eleven-year-old Angora Goat, or Tom, a seven-year-old Broad Breasted White Turkey. You’ll never forget them."

A few months ago I was asked to write an endorsement for award-winning photographer Isa Leshko's forthcoming book Allowed to Grow Old: Portraits of Elderly Animals from Farm Sanctuaries. I remember beginning to flip through the manuscript and accompanying biographies of each of these amazing nonhuman animals (i.e., animals), calling off plans for the night, and totally diving into this magnificent and heartwarming book. I wrote: Allowed to Grow Old is a priceless and heartfelt tribute in stunning images and moving words to elderly farmed animals—senior citizens—who had previously lived horrific lives. This beautiful book clearly reveals the individuality of each animal photographed, and shows that farmed animals are no different from the companion animals with whom we share our lives. They are sentient beings with unique characters and personalities, who simply want to live out their lives with lots of love and in peace and safety. As an ethologist who has studied the emotional lives of a wide variety of animals, I could easily feel what each individual was feeling when they were photographed, and could well imagine the lives they have led.

Now that Ms. Leshko's book has been published, I find myself flipping through it over and over again and being totally absorbed by each and every image. I was thrilled she could take the time to answer a few questions about her landmark work. Excerpts from our interview follow. (Complete biographies for the three individuals portrayed below are in Note 1.)

"Each time I witnessed these exchanges of affection, I marveled at these animals. They had every reason to fear human beings, yet they had come to trust, and even love, their caregivers. Their bodies may have borne the scars of earlier abuse, but their spirits clearly did not. Their resilience showed me the power of empathy and compassion."

Why did you publish Allowed to Grow Old?

I began this series shortly after caring for my mom, who had Alzheimer’s disease. The experience had a profound effect on me and forced me to confront my own mortality. I am terrified of growing old, and I started photographing geriatric animals in order to take an unflinching look at this fear.

As I met rescued farm animals and heard their stories, though, my motivation for creating this work changed. I became a passionate advocate for these animals, and I wanted to use my images to speak on their behalf. It seemed selfish to photograph rescued animals for any other reason.

From that point on, I approached these images as portraits, and I endeavored to reveal something unique about each animal I photographed. My goal was to dispel the stereotype that farm animals are dumb beasts. I am not saying that they are like the anthropomorphic barnyard characters in Charlotte’s Web. But they do experience pleasure and pain, joy and sorrow, fear and anger.

I do not claim to know what the animals in my photographs are thinking or feeling. It’s not possible to know precisely what animals are thinking or feeling—just as we can never truly know the inner lives of our fellow humans. But I want viewers of my images to appreciate that the animals in my pictures do think and feel. I photographed the animals at eye level because I wanted viewers of these portraits to gaze directly into my subjects’ eyes and have an intimate encounter with them.

I continued to focus on elderly farmed animals because it is nothing short of a miracle to be in the presence of a farm animal who has managed to reach old age. Fifty to seventy billion land animals are factory farmed globally each year. Most farm animals are slaughtered before they are six months old. By depicting the beauty and dignity of elderly farm animals, I invite reflection upon what is lost when these animals are not allowed to grow old.

How did you approach creating these images?

Rescued farm animals are often wary of strangers, and it can take several days to develop a comfortable rapport with the animals I photograph. I often spend a few hours lying on the ground next to an animal before taking a single picture. This helps the animal acclimate to my presence and allows me to be fully present as I get to know her.

I work only with natural light. I generally do not even use a tripod and instead stabilize my camera on my knee or on the ground. t. When editing my images for my book, I carefully considered whether the portraits I selected were respectful to the animals I had photographed. Many of the animals I met had lost teeth and drooled a lot. I wrestled with whether to leave this drool in my images or to remove it in Photoshop. I decided to include it because I did not want to impose any anthropocentric norms on these animals.

"The animals who appear in my book though are the lucky ones, despite their early traumatic experiences. Billions of animals each year never make it to sanctuaries. They lead brief miserable lives that end in bloodshed."

I really like the combination of moving images that show how each individual feels and the text that you and others wrote to accompany them. Why do you think that this is a good way to portray who these beings truly are?

Animal products are ubiquitous in our world, but farm animals themselves are culturally invisible. With Allowed to Grow Old, I'm trying to bring farm animals out of the shadows. I hope that readers will stop to consider these animals’ lives and recognize that they are individuals and not commodities.

Most of the animals I met endured extreme abuse and neglect early in their lives. My portraits are testaments to their strength and endurance. For that reason, I shared details about each animal’s life before they were rescued and placed into sanctuaries. I did not go into graphic detail, but I wanted readers to appreciate that these animals were survivors.

The animals who appear in my book though are the lucky ones, despite their early traumatic experiences. Billions of animals each year never make it to sanctuaries. They lead brief miserable lives that end in bloodshed.

What did you learn from working on your book?

Being in the presence of farm animals who defied all odds to reach old age taught me that old age can be a blessing and not a curse. I will never stop being afraid of what the future has in store for me after seeing my mother and my grandmother succumb to dementia in their final years. But I want to face my eventual decline with the same stoicism and grace that the animals in my photographs have shown.

While working on this book, I also learned that farm animals are no different from the dogs and cats I have known. I included a handful of portraits of elderly dogs in Allowed to Grow Old to exemplify this point and to raise questions about why we pamper some animals and slaughter others. At Indraloka Farm Sanctuary in Mehoopany, Pennsylvania, a pig named Jeremiah jumped with excitement when he saw Indra Lahiri, who nursed him back to health after he arrived there with severe pneumonia. Melvin, an Angora goat who lived at Farm Sanctuary in Orland, California, put his front hooves up on his fence when sanctuary staff approached his enclosure. He gave visitors gentle head butts that reminded me of the friendly greetings my cats give me. These animals had every reason to fear human beings, yet they had come to trust, and even love, their caregivers. Their bodies may have borne the scars of earlier abuse, but their spirits clearly did not. Their resilience showed me the power of empathy and compassion.

You visited farm sanctuaries across the country while working on this project. What are these sanctuaries like?

I feel a sense of peace when I visit these sanctuaries that I experience nowhere else. There is a sign at the entrance to Pasado’s Safe Haven Sanctuary in Sultan, Washington that reads, “Sweet creatures who pass this way once scared and alone…Now you are safe; now you are home.” I cried the first time I saw it.

At these sanctuaries, animals are given ample space to roam freely and indulge their natural behaviors. Chickens spend their days outdoors basking in the sun and taking dust baths. Their living conditions are vastly different from those of industry chickens who are densely packed in poorly ventilated, windowless sheds. On commercial farms, sows are so tightly confined that they can’t even turn around. At sanctuaries, pigs explore large pastures and soak in wallows. They sleep curled up together on fresh hay, often snoring loudly.

I am in awe of the people who work on these sanctuaries. Their jobs are physically and emotionally grueling: they work long hours outdoors in extreme temperatures and they witness firsthand the horrific abuse farmed animals endure. Death and loss are fixtures in their lives. Yet they are unwavering in their devotion to the animals in their care.

It’s important to note that those who work at farm sanctuaries recognize that they can only help a tiny percentage of the billions of animals in desperate need of rescue. But they offer another type of relationship humanity can have with farm animals, one that is based upon empathy and respect; not abuse and exploitation.

Most farm sanctuaries offer guided tours and I encourage people to visit them and support them. Both my book and my website have a list of the sanctuaries I visited while working on this project.

What are some of your current projects?

For my next long-term project, I intend to look at life at the opposite end of the spectrum by photographing farm animals at their birth. Sanctuary animals are either sterilized or segregated by sex to prevent pregnancies, so births at sanctuaries typically occur with recently rescued pregnant animals. Many of these births are at-risk due to the abuse, stress and poor nutrition that their mothers endured prior to their rescue.

Like with old animals, the line between life and death is razor thin in newborns. Stillbirths are not uncommon in farm animals, and even healthy babies are vulnerable and frail. As a spin-off project, I want to return to create portraits of each animal when they reach the average slaughter age for their species to illustrate that they are still just babies. Juxtaposing these portraits with my elderly farmed animal portraits will be especially powerful.

Note 1:

Ash, Domestic White Turkey, Age 8

As with a lot of rescued animals, not much is known about Ash’s early life. Her body, though, bore telltale signs that she had been reared on a factory farm. The tip of her beak had been severed, and her middle toes had been partially amputated.

Commercially raised turkeys and chickens live in large, windowless sheds so densely crowded that the birds cannot walk without stepping on each other. There is no room for preening, foraging, or perching. Birds living in these conditions are so stressed they become abnormally aggressive and even resort to cannibalism. Rather than improving the animals’ living conditions, farmers try to minimize the damage the birds can inflict on each other by debeaking and detoeing chicks within days of their hatching.

Babs, Donkey, Age 24

During the first seventeen years of her life, Babs had been used for roping practice on a ranch in Eastern Washington. Donkeys are inexpensive, so cattle ranchers often learn roping techniques on them instead of on mechanical dummies. Many rodeos also use donkeys for entry-level roping competitions. Roping involves electrically shocking a donkey to make her run, chasing her on horseback, and then tossing a lasso around her neck or rear legs to pull her to the ground. Donkeys endure this practice repeatedly until they are exhausted, maimed, or killed.

Teresa, Yorkshire Pig, Age 13

After being reared on a factory farm in North Carolina, Teresa was destined for the slaughterhouse at only six months of age. She was placed on a crowded trailer that was headed to a meatpacking plant in Pennsylvania. Along the way, the driver stopped at a bar in Washington, DC, parking his triple-decker truck on a city street. The pigs were left for hours in the summer heat with no air conditioning and no water. Over the next several hours, the Washington Humane Society received many calls from worried bystanders who heard loud squeals coming from the truck. Law enforcement seized the truck and brought it to the Poplar Springs Animal Sanctuary in Poolsville, Maryland. Though some of the pigs died, most survived, and forty pigs, including Teresa, were taken to Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, NY.