Ethics and Morality

Zoo Ethics and the Challenges of Compassionate Conservation

A comprehensive interview with Jenny Gray, CEO of Australia's Zoos Victoria.

Posted July 18, 2017

A few weeks ago I received a copy of a book by Jenny Gray, CEO of Zoos Victoria (Australia), called Zoo Ethics: The Challenges of Compassionate Conservation. I've been looking forward to reading Ms. Gray's book, and after I did I thought that the best way to get a discussion going would be to interview her. She agreed, and below are the answers to the questions I sent her. Let me say upfront that Ms. Gray and I differ in our views on zoos (please see, for example, "It's Still Not Happening at the Zoo: Sharp Divisions Remain), and that is why I was pleased that she took the time to answer these questions (some of which are preceded by statements about how we differ). Compassionate conservation is a rapidly growing global and interdisciplinary discipline that is concerned with captive and free-ranging animals, and I also was pleased to see Ms. Gray take up the various challenges that compassionate conservation presents.

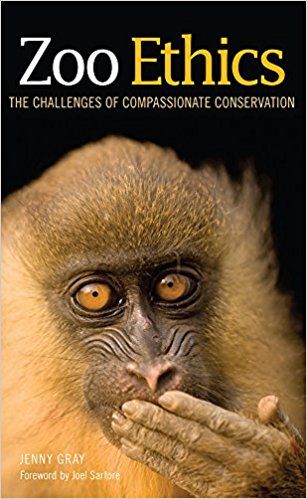

The description for Zoo Ethics reads:

Zoo Ethics examines the workings of modern zoos and considers the core ethical challenges faced by people who choose to hold and display animals in zoos, aquariums, or sanctuaries. Jenny Gray asserts the value of animal life and assesses the impacts of modern zoos, including the costs to animals in terms of welfare and the loss of liberty. Gray highlights contemporary events, including the killing of the gorilla Harambe at the Cincinnati Zoo in May 2016, the widely publicized culling of a young giraffe in the Copenhagen Zoo in 2014, and the investigation of the Tiger Temple in western Thailand.

Gray describes the positive welfare and health outcomes of many animals held in zoos, the increased attention and protection for their species in the wild, and the enjoyment and education of the people who visit zoos. Zoo Ethics will empower students of animal ethics and veterinary sciences, zoo and aquarium professionals, and interested zoo visitors to have an informed view of the challenges of compassionate conservation and to develop their own ethical positions.

Why did you write Zoo Ethics: The Challenges of Compassionate Conservation and how did your writing your book stem from your long-term affiliation with zoos?

Thank you for the opportunity to talk about my book and the ethical challenges facing people who choose to work for animals. Zoo Ethics is a reflection of my journey to understand the ethical landscape of working with animals in zoos or other facilities. Many people have strong opinions about zoos and aquariums, however, few take the time to develop coherent arguments, supported by facts and real data. I hope Zoo Ethics will be read by people working for animals or interested in animals and that they will then take the time to develop their own arguments on what is morally acceptable. My fondest hope is that when we think deeply about ethics and morality we can see the need for change and secure the will to change.

What are your major messages?

In writing Zoo Ethics, I learned that there is no single knock out argument for or against zoos. Rather, each ethical framework (welfare, rights, consequentialism, virtue and environment ethics) provides a way of thinking about animals and our relationship with animals. I would encourage people to read and think deeply about the duties and obligations that we have to animals.

My take is that you defend zoos and believe it is perfectly okay to keep animals in cages for a number of reasons. What are they and why is this so?

I think that is it morally acceptable to house animals in captivity when it can be shown that this is in the interest of the individual, the species or the environment. Captivity may be in the interest of an individual when the alternative is death or suffering and where the captive conditions provide predominantly positive welfare states. The judgement of zoos and aquariums is based on all the things they do, there is no single argument that either justifies or condemns zoos.

There are on-going discussions and debates centering on the educational role of zoos and their contributions to conservation. I don't find playing the "education card" especially compelling in terms of how people who learn something actually then go on to make significant contributions to the future of captive animals and/or their wild relatives. What do you believe about the role of zoos in this arena? I also feel that playing the "conservation card" is a bit different, in that there are some zoos that do make significant contributions to conservation projects, but they do not really help the zoo's residents. However, given the number of zoos worldwide, only a very few actually do anything for conservation so it's difficult to justify keeping animals in captivity for conservation purposes. Can you briefly tell readers what your take on zoos and conservation is? (Very long question – more of a statement)

When we consider that 50 percent of species are now listed as endangered and many species are in an absolutely critical condition, I think we need every bit of help we can get to prevent the sixth mass extinction. Zoos and aquariums are one player in a complex undertaking. I think that zoos and aquariums have a role in housing and breeding endangered species and I am encouraged to see more facilities committing space and resources to endangered species. Of course, more must be done.

In terms of education, you are correct all education (including schools and universities) has failed to stop environmental destruction to date. Now we need to act together to inspire people to take action to protect animals. Behaviour change experts refer to the moment of impact which is when people are aroused and motivated to hear a message. We now have evidence that zoos and aquariums are able to provide profound experiences which inspire behaviour change and action for animals (for example, Ballantyne et al 2007; Jensen et al 2017; Moss et al 2015; Packer and Ballantyne 2010; but also more specifically related to campaigns -- Mellish et al 2016; Pearson et al 2014).

On page 118 you write, "While meeting the moral requirement of ensuring that zoo animals do not suffer is achievable for most species, I expect that discussions on the potential for some species to be considered as non-human persons will one day lead to limiting the range of species that zoos may hold and display, or at the very least will pose additional obligations on those that care for non-human persons." (my emphasis) And, on page 151 you wrote, "If the welfare of the animals can be accommodated, as arguably it can for most species, then it seems appropriate for to take joy in seeing nature up close ..." (my emphasis) What about individuals of species who do/will suffer and can't be accommodated? What do you think about the Detroit Zoo's snail exhibit that is very effective at getting across principles of biodiversity and conservation?

Over time the animals housed at zoos and aquariums have changed. At Detroit Zoo they talk of fewer animals in larger spaces. I think we will continue to see larger animals with significant space requirements moving out of city zoos, into safari parks and open range facilities. City zoos will house fewer big animals and increase the number and quality of smaller animals, including invertebrates and reptiles. These displays, like the snail exhibit in Detroit, are able to meet the needs of the individual animals and also to be impactful in terms of conservation messaging. Around the world there are many such exhibits including the locust exhibit at Basel Zoo in Switzerland, burying beetles at St Louis Zoo and the conservation story of the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect at Melbourne Zoo. The butterfly house at Melbourne Zoo constantly ranks as one of the most popular exhibits. We will all benefit from pausing and considering the diversity of species that share the planet and providing opportunities to connect with the small and amazing. But even here we have a duty of care and must understand the needs of the small critters.

On page 208 you write, "Unfortunately the bulk of zoos in existence today still fall short of meeting the requirements of ethical operations. At best, 3% of zoos are striving to meet ethical standards, with perhaps only a handful meeting all the requirements. But there is hope." Can you please tell readers why you are hopeful that the future will be better for caged animals who Jessica Pierce and I call "zooed' animals in our book The Animals' Agenda: Freedom, Compassion, and Coexistence in the Human Age when you note that there will be individuals of some species who can't really ever have a life without suffering while they live in a zoo, and that around 97 percent of zoos today don't even strive "to meet ethical standards"?

In my time as a Zoo Director I have seen increased interest and investment in zoos and aquariums. The needs for engaging communities with nature and putting biodiversity in front of an increasingly urbanising population has given zoos and aquariums a new and important role. Many of the problems we see in zoos are linked to knowledge gaps, resource shortages and cultural attitudes. Increased interest in animal cognition is increasing knowledge and increased knowledge is challenging belief. No doubt social media pressure is also increasing the pressure for change.

I am increasingly inspired by the people I meet that work in zoos. Professional staff are smart, passionate and committed to a sustainable future. They join zoos and aquariums to change both the zoos and the attitudes of visitors. Provided with knowledge and resources, I am confident they will create improvements that we have not even thought of.

All these factors give me hope that we will see significant change in facilities that hold and care for animals.

In various places you write about vulnerable and dependent animals. On pages 155-156 you write, "When humans hold a position of dominance over others, thereby creating a relationship of vulnerability and dependence, it is incumbent on the virtuous to exercise great compassion." What do you mean by this?

When we choose to bring an animals into our homes as pets or to house an animal in an enclosure we create the conditions where they can no longer fend for themselves. Your dog relies on you for food and shelter but also for company and emotional support. It is not enough to simply make sure they have enough resources to stay alive and to not suffer, you also have to make sure that they thrive. You must act with compassion and consider what each animals needs mentally, emotionally and physically. I believe that we should never be comfortable that we have done enough. Every day we should find ways to do more.

Among the guiding principles of compassionate conservation are "First, do no harm" and the life of every individual matters. Just what can compassionate conservation contribute, or better yet add, to debates about whether zoos should exist in the first place and that it's ok to keep animals in cages either for their supposed good or for purposes of education and conservation?

It is not my goal to consider a world where zoos and aquariums don’t exist, so from the outset I am clear that I assume zoos and aquariums will continue to exist. Rather I would like to challenge readers to consider how ethics can help us think about our relationships and obligations to animals in our care. Zoos and aquariums are contributing to conservation and I suggest that the contribution can be improved by considering compassionate conservation. For too long it seemed that we need to choose to either prioritise the individual or the species. I think when we care for individuals and for species we will develop kinder and more successful conservation programs.

How have the principles of compassionate conservation influenced your thinking about the importance of the life of every individual?

At Zoos Victoria we have changed the way that we prepare animals of endangered species for release. Through predator awareness training we have increased the survival rate of individuals in one program for 45 percent to over 90 percent. Clearly this is good for both the individual and the species. We have also changed the ways that we house animals. Every year we upgrade and expand animal facilities, increasing the things that we now know they need to thrive, including cognitive challenge, quiet retreat spaces and options for control over their environment. We employ animal welfare scientists whose job it is to conduct animal welfare assessments on the individual animal level using validated scientific assessments of welfare (behaviour and physiology). We have 46 research projects in progress all focussing on advancing welfare across various species from butterflies to gorillas. This research allows us to make informed animal management decisions that are in the best interests of individual animals in our care.

Many zoos partake in what they call "management euthanasia" of so-called "surplus animals." I have many problems both with the use of the word "euthanasia" and the phrase "surplus animals." In a section of your book you pose some very interesting and challenging thought experiments that raise a number of issues with how zoo administrators deal with different sorts of animals. On pages 214-215 you consider the topic of "Killing Surplus Animals," focusing on the fate of Marius, a young and healthy giraffe who was killed (not euthanized, despite what they claim) at the Copenhagen zoo, because it was decided that Marius couldn't contribute to the zoo's breeding program. A bit after Marius was killed, four lions were killed at the same zoo for the same reason. At a meeting at the Detroit Zoo in May 2017, where we met, someone referred to the director of the Copenhagen zoo who decided that it was perfectly okay to kill Marius as a hero. I frankly find this to characterization be perverse and the slaughter of Marius and the four lions to be unacceptable -- many others and I don't find this to be a complex issue at all -- and I wonder if you would have chosen to kill Marius or other animals who you decided couldn't contribute for one reason or another to your zoo's breeding program.

I agree that there is a difference between a death that is in the interest of the individual (euthanasia) and killing which terminates a healthy life. I challenge readers to think about the issues in the wicked questions section, including the death of Marius, and develop their own arguments. I have deliberately not given simple answers to what are complex issues. Many arguments can be mounted. I would hope that students of ethics can refine not only their personal view but also the plausible arguments to the contrary.

What do you think about turning zoos into sanctuaries?

In Zoo Ethics I define zoo to include all facilities that house animals in a captive state, including zoos, aquariums, sanctuaries, butterfly gardens and reptile parks. ‘Sanctuary’ is a word with positive context which is often undeserved. While there are amazing sanctuaries, run by well-meaning staff, there are many more that are truly terrible without the funds or the expertise to care for animals well. I would not judge a facility on the name or the size of the bank balance, but rather on the attention, research and effort they put into the care of the animals they hold and the impact they make on conservation and education. I have seen simple facilities that have extraordinary animal care and big, rich facilities with terrible animal care.

How do you feel about virtual zoos?

I am interested in how technology will help improve the lives of captive animals. If documentaries were enough then we would not be facing the Sixth Extinction and zoos and aquariums would not receive the visitation they currently experience. While I don’t think technology will replace zoos and aquariums I do think that technology can enhance visits. At Zoos Victoria we use technology to show animals we would not hold, for example in our ‘deep’ aquarium there is a huge screen where whales swim past. Technology can also bring to life the threats to wildlife at the point that people are in the presence of a real animal. We show the impact of balloon litter on seabirds, without harming our own seabirds, and provide the opportunity to pledge to blow bubbles instead of releasing balloons. In 6 months 41,000 people have already taken this pledge. We’re also investigating options for virtual reality combined with real life sensory experiences of animals to enhance conservation empathy in some of our cryptic species like Baw Baw frogs. The combination is likely to be powerful.

Technology allows for observations without human impact and the widespread use of cameras allows us to undertake new research into animal behaviours and the impacts of various activities on animal well-being. For example we use thermal cameras to monitor animal behaviour overnight and nest box cameras to non-invasively monitor Little Penguin chicks. We also use technology to help us deliver food at random times throughout the day to a selection of species that benefit from unpredictable feeding regimes. We also discover interesting capacities that show how little we truly know about the other intelligent beings that share our planet.

What are some of your present and future projects?

Zoos Victoria will continue to champion the importance of zoo based conservation. We are excited about the projects that we support and run. This year we will release a second population of Eastern Barred Bandicoots on Philip Island, starting the process of delisting a species currently listed as extinct in the wild. To champion the first mammal recovery in Australia is an exciting endeavour. We will expand our breeding for release programs focused on recovering the 21 most endangered species in Victoria.

We will continue to campaign for labelling of palm oil on food in Australia, protection of forest environments and less ocean litter. We will also continue to put critically endangered animals in front of people, through live exhibits, educational programs, photo galleries or documentaries. I believe that most people will change their behaviours, even just a little, when they see what we are about to lose. It is devastating to truly consider a future without lions or elephants or mountain pygmy possums.

Underpinning all of these conservation goals, we are continuing to drive progress in using science to advance animal welfare standards in our own backyard but also across the industry in general by working to upskill animal professionals and spread knowledge and learnings.

On the global stage I have just taken on the role of President of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. The position provides me with great platform to talk about animals, conservation and our responsibilities as ethical beings.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell readers?

We live at a time when animals are under extreme threat. Over 50 percent of animal species are endangered. The biggest threat to animals is humans. The scale of the threats to species survival requires many solutions. I hope that learning about ethics will help us make sure that we find effective interventions that are compassionate and consider the interests of each animal impacted.

Thanks so much, Jenny, for answering these questions. I was hoping that you would have answered the question of whether you would have supported killing Marius.2

Having said that, I hope your interview reaches a broad global audience because these questions and debates, along with others, are not going to disappear if they're ignored. It's important for people to speak openly about how they agree and how they differ about whether, for example, it's permissible in the first place to keep animals in cages, whether captive breeding should continue, if it's okay to kill healthy animals who can't contribute to a zoo's breeding program, if zooed animals should be shipped around for mating or other purposes, whether they should be forced to mate, and what the future of zoos should look like. And, since only a tiny percentage of zoos are trying to meet welfare standards, it's clear that the well-being of numerous individual animals is routinely ignored in zoos around the world. The keeping of animals in zoos shows just how animal welfare fails individuals of numerous species.1

For those who want to learn more about compassionate conservation there will be an international conference held in Sydney, Australia, this coming November, and sources that present wide-ranging discussions about zoos and other areas in which compassionate conservation can play an important role are Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation, "Compassion as a Practical and Evolved Ethic for Conservation," "Promoting predators and compassionate conservation," "Compassionate Conservation Meets Cecil the Slain Lion," and the website for The Centre for Compassionate Conservation.

We are the lifeline for captive and free-ranging animals, individuals who totally depend on our goodwill and our putting their well-being first and foremost in an ever-increasing human-dominated world. Compassionate conservation surely can, and should, lead the way.

1For a rather different view on zoos please see this interview titled "These haunting animal photos aim to make you reconsider a visit to the zoo" with noted photographer, Jo-Anne McArthur, about her new book called Captive. Also see "The Whale Sanctuary Project: Saying No Thanks to Tanks" and an interview with Dr. Lori Marino, President and Chairperson of the board of The Whale Sanctuary Project.

2I've added this because of a good number of people mentioning that they, too, would have liked an answer to this question by a prominent zoo administrator, rather than saying it's a complex issue etc etc.

Marc Bekoff’s latest books are Jasper’s Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson); Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation; Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation; Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence; The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson); and The Animals’ Agenda: Freedom, Compassion, and Coexistence in the Human Age (with Jessica Pierce). Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do will be published in early 2018. Learn more at marcbekoff.com.