Career

The Great Resignation Is Mostly a Great Overhype

Total quit rates are up, but most industries have seen less than a 3% increase.

Posted January 24, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

The media never ceases to feed us terminology that comes with plenty of baggage, and the latest of these has been the "Great Resignation"[1]. Wikipedia perhaps provides the direst description when it describes the Great Resignation as an “economic trend in which employees voluntarily resign from their jobs en masse” (para.1, emphasis added). Many members of the media, from the Guardian to USA Today, have happily offered stories about “historic” and “record” quit rates. Other sources have lined up to share “expert” advice or sell consulting services (such as McKinsey & Co. and Gallup), all to ensure they don’t pass up the opportunity to use fear of the Great Resignation to its fullest benefit.

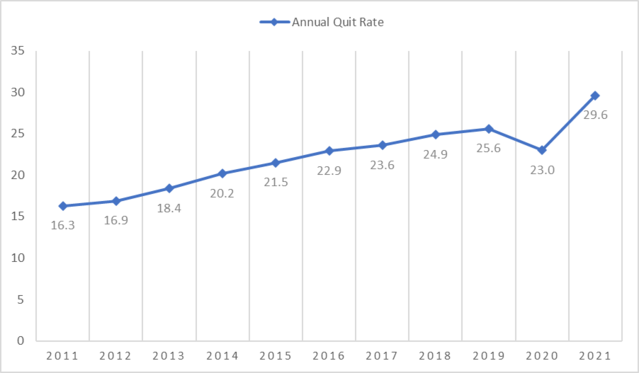

To be fair, total non-farm annual quit rates since 2011 appear to be quite high (Figure 1), much higher than at any point since 2011. But, to conclude this represents some sort of mass, great, or historic period of resignation would be highly erroneous. After reviewing the data through November 2021 and looking at some other sources, it seems evident that claims of a Great Recession have been dramatically overhyped, especially when discussed as some sort of broad trend. In furtherance of my own claim, consider the following.

Low-Skill and Blue-Collar Industries Are Driving the Bulk of the Increases

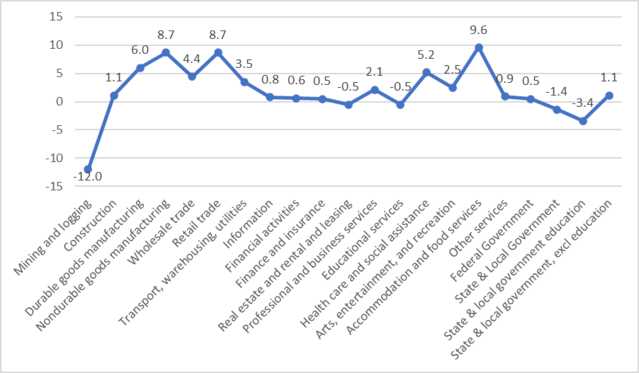

Figure 2 presents the difference between total annual quit rates from 2021 and the highest annual quit rate from 2011 to 2020 (all rates totaled through November) for each of the various Department of Labor industry categories. What becomes evident is that low-skill and blue-collar jobs represent the bulk of the increase in quit rates, with accommodation and food services (9.6 percent higher), retail trade and nondurable goods manufacturing (8.7 percent higher), and durable goods manufacturing (6 percent higher) leading the way. Healthcare and social services (5.2 percent) is the first professional field to enter, at #4. Some industries that might have been expected to see higher quit rates, like real estate (-0.5 percent) or education (-0.5 percent), have actually seen lower quit rates than they had in at least one of the preceding 10 years.

Many industries have seen higher quit rates than they have since 2011, but by no means would this be considered some sort of “en masse” trend. The median difference across industries is only 1.1 percent point higher than at some point between 2011 and 2020 (and a mean of 1.82 percentage points). Instead, workers employed in low-skill or blue-collar industries, where much of the work cannot be done except on-site, drove the seemingly massive overall quit rate.

A Sizeable Percentage of Current Quit Rates Are Likely Those Over Aged 65

This point was emphasized recently by Thompson (2021), who pointed out that among those 65 and older, participation in the workforce is down more than 10 percent since before the pandemic. As pointed out by Schramm and Figueiredo (2020), workers aged 60+ represented about 15 percent of the workforce, with about a third of them falling into the essential worker category. Given the increased risk of COVID complications for this age group, it is unsurprising that many of them decided to stop working. Although the number of workers 65+ who simply decided to leave the workforce explains only a small overall percentage of actual quit rates (about 1.5 percent), it would be unsurprising to find that another sizeable percentage quit their current job in favor of safer employment.

There’s No Evidence the Current Quit Rates Are Historic

Zagorsky (2022) pointed out that current quit rate data only goes back to 2001. Thus, any claims of “historic” or “record” quit rates are based only on data from the past 20 years. Certainly, overall quit rates are higher than they have been since 2001, but that assumes that the quit rates wouldn’t have been higher during the "dot.com" bubble or post-WWII, both periods in which the economy was in a state of radical flux. Thus, it seems highly unlikely that these are historic or record quit levels.

What To Make of All This

Psychologically, it makes sense that some industries would see increased quit rates. For many of the industries that saw markedly higher quit rates, the pandemic introduced additional challenges for workers that likely made the costs of maintaining the status quo (which is usually preferred[2]) higher than the benefits of doing so. As I mentioned in my last post, fear can be a powerful motivator, and COVID coverage likely created an incentive where one may not have existed before the onset of the pandemic.

As such, many workers were motivated to seek a change, a desire for higher wages, greater perceived safety in their work environment, and other reasons. As businesses began to re-open in 2020, there were more job openings, sometimes with higher pay, leading to a perfect storm for increased quit rates in a small subset of industries.

Many of these same industries that are seeing increased quit rates are also seeing increased hiring rates, which is likely to result in the second-highest hire-to-quit-rate differential since 2016[3] (sitting currently at 17.8 percentage points). In other words, industries are hiring a lot more workers than they’re losing. Given the increased hiring and the massive disruptions that have happened in multiple workplaces, it is unsurprising that close to a third of workers were looking for a change[4].

Much of what is available online in terms of discussions of the Great Resignation assumes that the spike in quit rates is driven by professionals. However, the benefits of many professional jobs actually outweighed the costs incurred as a result of COVID, as many of these workers experienced benefits due to the switch to remote work (e.g., decreased commuting time, increased satisfaction, and higher reported productivity). The same could not necessarily be said for many lower-wage or less-skilled workers, making the cost-benefit analysis of maintaining the status quo much more untenable.

As such, when we look at the data itself and better understand the psychology that goes into employment decision making, it becomes more evident that The Great Resignation has been nothing more than The Great Overhype, except in a few industries. How organizations opt to manage issues moving forward, though, could determine whether we end up seeing comparable quit rates in more professional industries.

References

Footnotes

[1] Coined in May 2021 in a Bloomberg article.

[2] [1] What is also known as status quo bias.

[3] 2020 was the highest in the past 11 years, with a 24.7 percentage point difference between total annual hire rates and total annual quit rates.

[4] In some cases, this has led to increased wages in these positions, as companies seek to offer competitive salaries to attract potential workers.