The Murder-Suicide Mission

Adrian Loya staged a baroquely premeditated murder to exact revenge for an assault that did not, in fact, occur. His motives, and the range of psychiatric diagnoses that shadowed him, reveal the difficulty of untangling mental fitness and criminal intent.

By Patrick Flanary published July 2, 2018 - last reviewed on July 17, 2018

On the cold, early morning of his 31st birthday on February 5, 2015, Coast Guard Petty Officer Adrian Loya was prepared to die. But first, he had to kill his "rapist."

He obsessively planned the attack after more than a year of nightmares, panic attacks, and a stomach-churning hatred that consumed him. He believed that he had been sexually assaulted by a colleague. Now, the victim had come for the villain. "I will die knowing that I did the right thing," he warned in his thick manifesto titled Loya Wars. The 250 typed pages detailed a murder-suicide mission, and it boiled down to two words: "Terminate her."

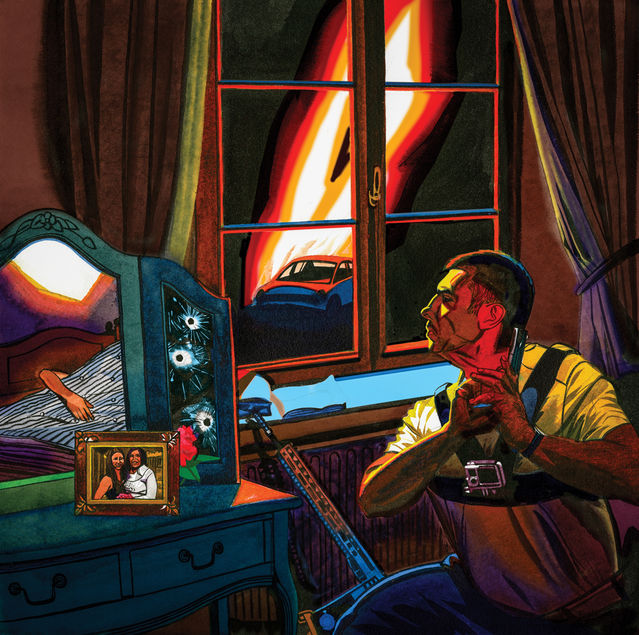

Loya had driven several hundred miles, from Virginia to Massachusetts, where patches of frozen snow covered the ground. Just after 2 a.m. on that February morning, he strapped a GoPro camera to his chest and began recording to document what he thought would be his final moments. Loya's "mission" was underway. Using a shotgun, he blasted into the Cape Cod home of his former colleague Lisa Berlanga and ran upstairs.

Armed with an AR-15 style rifle and a pistol, Loya was ready to "strike fear into her as the last sensation she would ever have." He had written these words just days before. But the guns were for show. Instead, the plan was to slit Berlanga's throat, tie up her wife Anna Trubnikova, then provoke police in an epic shootout that would end with Loya's demise.

But Loya did not die. He wasn't even harmed. The plan was doomed from the moment he burst into the terrified couple's bedroom and pulled off his ski mask. "You had two years to say you were sorry," Loya yelled at Berlanga. He hadn't expected the fear in her eyes to throw him off. He was having second thoughts. Worse, he knew he was losing control. When the women suddenly panicked and threw up their mattress for cover, Loya emptied his nine-millimeter into the barrier, killing Berlanga instantly.

Loya had blocked the entrance to the neighborhood with his Mazda, which he had set on fire. After the murder, as he waited impatiently for the cops, he created still more distractions, scattering hoax bombs and cranking the sinister theme songs from Batman Begins and the James Bond movies on a large boombox. The neighborhood shook. Loya had staged an elaborate scene, "like Spielberg setting up a movie," as one psychiatrist would later testify.

Anna Trubnikova was shot four times in the volley that killed her wife, and she was on the phone with dispatchers for an hour thereafter, as Loya moved about the property deploying his theatrical props. Outside the condo, medics struggled to get inside to her.

Finally, seeing the silhouette of a police officer, Loya squeezed the trigger of the semi-automatic rifle. The officer dropped to the ground, wounded. When the officer didn't return fire, a year's worth of preparation disintegrated. At 2:48 a.m., there was nothing left to do but surrender. By surviving his "mission," Loya had failed to win his war.

A Life of Underachievement

Adrian Thomas Loya was born February 5, 1984, in El Paso, Texas, the first of three children, to Shirley Guerrero and George Loya. His parents lived apart, and for months his father wasn't even aware of Adrian's birth. They married when he was 2, but divorced less than two years later.

His mom said that when Loya was about 8, his behavior often shifted from withdrawn to confrontational. One minute he was emotionally unresponsive, the next he was volatile, usually toward his younger sister and brother. Shirley wanted Adrian to see a counselor, but George insisted their oldest child was just going through a phase.

When his mother and siblings moved to San Antonio, Loya stayed with his father to finish high school in El Paso. While he was a capable swimmer on the Burges High School swim team, Loya often neglected his homework and generally did poorly in school.

A month after he turned 21, eager to leave his dad's house, he joined the Coast Guard. Loya craved the structure and security that the service offered. The service saved lives, it didn't take lives.

"I'm not supposed to be alive right now," Loya says.

Seated in the visiting room of the Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, Loya wore forest-green inmate scrubs. Throughout the 75-minute conversation, he maintained eye contact and a soft-spoken demeanor as he addressed the gruesome details behind what put him there.

"Lisa didn't deserve to die," Loya says. "But she wasn't innocent. She still did something, and she wasn't remorseful for what she did."

Loya has long claimed that Berlanga, a fellow petty officer, sexually assaulted him in 2012 in Alaska, where they were stationed as information systems technicians. (She took her wife's name, Trubnikova, but for clarity we use her maiden name here.) Less than two hours after he surrendered to police, Loya told them in taped interviews that he killed her in retaliation for "a rape of the mind."

At his trial in September 2017, a jury deliberated whether a mental illness impaired Loya's ability to know right from wrong when he executed the calculated attack.

Lawyers for the Commonwealth argued that Loya premeditated Berlanga's murder with extreme cruelty. The evidence was there: the tell-all manifesto, the cross-country stalking, the eager confession. As Juror No. 7 later said, "If you look in the dictionary under premeditated, there's a picture of this guy."

But the defense claimed that Loya was delusional leading up to and during the murder, and therefore not criminally responsible for confronting what he considered a monstrous injustice. Expert witnesses offered completely conflicting diagnoses for Loya's behavior, making his a case in which the vengeful motive for the murder was as unusual as its dramatic staging.

A Rape of the Mind

It was during a Coast Guard morale event in September 2011 when Loya met a petite brunette named Lisa Berlanga. They discovered they'd grown up a few hours apart in Texas. Both had listed Kodiak, Alaska, as their last choice for a tour of duty, yet here they were. They shared a dry sense of humor, often trading references from the offbeat TV series Arrested Development.

Before Berlanga got to Alaska, homebody Loya kept to himself, playing video games or shopping online; once, for his birthday, he bought himself a sword for $450. Now, with the funny and attractive Berlanga, Loya hoped he had found his new best friend, even if she was about to marry.

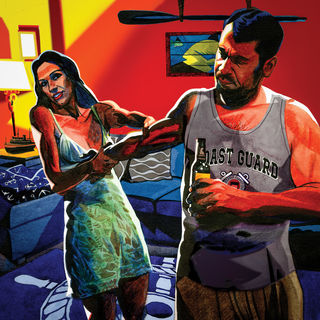

When Loya later realized she was gay, he regretted having casually used the slur "faggot" in her presence. And though he detested the overall concept of marriage, Loya expressed happiness for Berlanga and her fiancee, Anna Trubnikova, a Coast Guard reservist. When Trubnikova arrived in Alaska, however, she was suspicious of possible ulterior motives, so she demanded that her wife limit contact with him outside of work. Loya resented her assumptions.

Meanwhile, in the office, a fracture grew between him and Berlanga. There were passive-aggressive run-ins and many months of tension with his former friend. So it felt like old times when she invited Loya to her place one night in September 2012. But it was well after midnight, she was drunk, and her wife was away on three-week duty. According to Loya's writings, as they sat on the couch watching The Simpsons, he grew increasingly anxious as she began masturbating next to him.

Loya claims Berlanga tried to kiss him, then she pulled him by the arm to her bedroom. "Come on. We can do it," she said, according to the manifesto. "It's okay as long as we don't tell Anna." Despite his attraction, he repeatedly said he could not fathom crossing that line. But Loya's body shook when Berlanga persisted, "Dude! What the f*ck is your problem, man? Just come to bed." While there was never sexual penetration, Loya developed "the delusional belief that Lisa had raped him," John Daignault, a forensic psychologist for the defense, later testified.

It all hit Loya at once: Visiting an intoxicated colleague—his subordinate—was a mistake he could never take back. He wrote in his manifesto that his mind raced: "What if she turns this around on me? What if this ruins our friendship? Worst of all, what if the Coast Guard discharges me?"

Berlanga apologized the next day, and made Loya promise to keep the encounter a secret.

Seeking Help

Loya feared repercussions. He was desperate to get ahead of any potential claims if she suddenly accused him of something. So he confided in several people, including his only buddy from high school and his father, with whom he rarely spoke. Everyone was more curious than sympathetic: Why didn't he sleep with her?

The following month, Loya visited the base's work-life office to get the incident on record, just in case. He was asked if he was suicidal. He lied and said no; admitting that he wanted to kill himself would have resulted in a discharge, he wrote.

Loya later approached his chief, who laughed off the accusation: A married lesbian raped you? Loya's request for a base transfer involved too much paperwork, he was told, but he was granted a new desk away from Berlanga. Another month passed. One day a routine sexual assault prevention course with his unit became too much to bear. During the training, Loya burst into tears and told Berlanga: "I hope you took notes."

In February 2013, Loya decided to confront her with written documentation of his mental state. He spent weeks typing a 19-page letter he called The Lisa Effect. "I have never been so scared in my life," Loya wrote, adding how he was torn between a crush and "a classic case of post-traumatic stress disorder because of what you did to me that night." While composing the note, he found himself going down the Wikipedia rabbit hole, diagnosing himself with labels, including Stockholm syndrome and battered woman syndrome.

To ensure transparency, Loya sent a copy of the letter to Anna Trubnikova.

With tension at the office coming to a head, and his Kodiak tour nearing its end, Loya met with agents from the Coast Guard Investigative Service. They doubted a sexual assault had occurred. Still, while they looked into it, they recommended that Loya pursue counseling. In April, he began seeing a therapist and continued doing so for his remaining nine weeks in Alaska. During one of those hour-long sessions, he was advised to avoid Berlanga, to let it go. Therapy, Loya later wrote, "made me worse." In May 2013, he left Alaska, vowing to revisit counseling once he arrived at his new post, in Chesapeake, Virginia.

That therapy never materialized. Minutes after reporting for duty on July 2, 2013, Loya was notified that the investigation in Alaska had closed, and he was furnished with a disciplinary report, reprimanding him for harassing Berlanga and causing "individual angst and decreased productivity" within the division. Loya's sexual assault claim had not only backfired, it now threatened the job he lived for. And, aside from being written up for alcohol use, Berlanga faced no punishment. "That was the first time I ever felt hate," Loya says. Toward the end of 2013, Loya decided he wanted out of the Coast Guard, and out of life entirely. He would not re-enlist, but he would kill Berlanga.

He roiled over the the seeming injustice: "If I'm gonna die, she shouldn't get away with this; she's just going to do it again," he says. "By July 2014, I thought, 'Well, if I'm gonna keep thinking it, I gotta get it out of the way by actually doing it.'"

Loya embarked on what he calls "a basic assassination mission." A search of Coast Guard files turned up Berlanga's new address, in New England, some 600 miles north of Chesapeake. Twice he made the drive: first, in October 2014 to stake out the address, then four months later for the "Final Battle."

By that point, it had been almost two years since Loya and Berlanga had spoken. As he recalls, the absence of anticipation assured him he was ready to kill her:

"Going to their house that night, there was no feeling. That's what creeps me out the most about myself, that I felt nothing. I was going to my death. Felt no fear about going to my death, no anxiety, no shaking, no butterflies.... But that night at Lisa's house in September 2012, that was the scariest moment ever; I was feeling all the terrifying sensations of just a woman trying to kiss me.... It was scary seeing [the couple]. But it was nowhere near that bad night at Lisa's house."

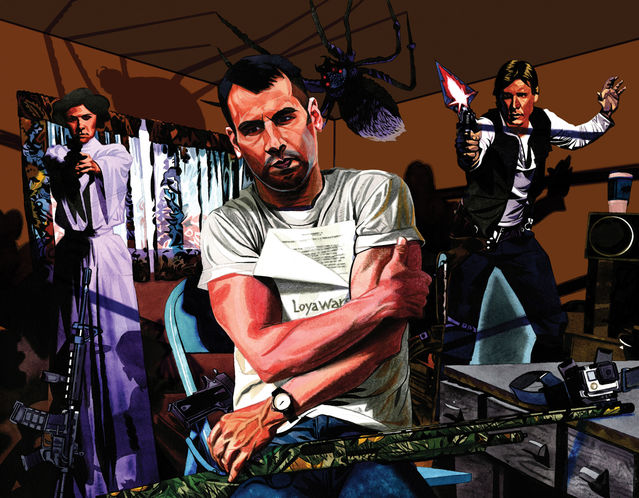

The deadly attack he scheduled for his birthday was the only thing keeping him alive. Days before Loya drove to Room 101 of the Quality Inn in Bourne, near the Trubnikova home, he tied up loose ends. He called his parents, telling them not to get in touch on his birthday. He gave away boxes of stuff, notably his airsoft rifle and Star Trek uniform. The last thing Loya did before he left his apartment in Chesapeake, Virginia, was to have some fun. To greet the bomb squad he knew would search his place, Loya set up cardboard cutouts of an armed Princess Leia and Han Solo. He greased the floor with gun oil and suspended a large fake spider from the ceiling. Then, on Super Bowl Sunday, Loya left for Massachusetts, knowing he could slip away on the one night of the year when almost everyone was focused on the game.

Differing Diagnoses

When a murder happens on Cape Cod, J. Drew Segadelli gets the call. He has defended more than 40 accused killers, an achievement proudly displayed in bold script on the side of his boat: Crime Pays.

But when the state's public defender agency assigned him to represent Loya, Segadelli initially had some concerns. The murder had happened in his hometown, and the injured cop forced into early retirement was a friend. Still, Segadelli believed Loya's mental state at the time rendered him incapable of appreciating the wrongfulness of his conduct. Convincing a jury was another thing. Segadelli says, "They have a really hard time swallowing such a defense."

"He could have changed his mind three seconds before he shot that gun," Juror No. 2 said. "He wanted to do one thing and one thing only: He wanted to maim and kill."

Loya calmly admitted as much in taped interrogations. He was arraigned on 30 charges, then placed on suicide watch at Bridgewater State Hospital, a half-hour northwest of Bourne. There, health professionals diagnosed Loya with major depressive disorder, but he was deemed competent to stand trial.

For jury selection, Loya rode to Barnstable Superior Court in handcuffs and shackles. On the way, he heard a radio report about the trial; it also praised Berlanga's work ethic. He says he had a "torturous" panic attack.

Loya was barely recognizable when he entered the courtroom. The baby-faced, heavyset suspect had shed about 50 pounds since his arrest and morphed into a slender, camera-ready defendant. As it happened, a BBC video crew from London was there to document the trial. With his six-foot-two-inch frame, full beard, and narrow, piercing gaze, Loya resembled the actor Jason Lee from Vanilla Sky. He hadn't visited either of his parents in years, but his mom was watching, streaming the trial online, from her home in Albuquerque.

At the trial, Loya's attorney called one witness to the stand. Forensic psychologist John Daignault was the first to evaluate Loya and had spent the most time with him: 48 hours across 17 sessions.

In his evaluation, Daignault noted that Loya suffered delusions of the persecutory type, involving "beliefs of being conspired against, cheated, spied on, followed, maliciously maligned, harassed, or obstructed in the pursuit of long-term goals." Daignault added that the delusions were amplified by a major depressive disorder resulting from the Coast Guard's disciplinary action. "Lisa was his enemy," Daignault testified. He concluded that Loya's state of mind met the Massachusetts standard for lack of criminal responsibility: "He's crazy." The judge stifled a laugh at that statement.

Psychiatrist Martin Kelly, retained by the prosecutors, offered a similar assessment. He also believed Loya was delusional as he sought "moral vengeance" in the months leading up to the murder. Loya was fascinated with heroism and the good vs. evil narrative of Star Wars, and was committed to replicating the fantasy. Kelly's diagnosis was high-functioning autism, known as Asperger's syndrome. And with that, two of the trial's three forensic expert witnesses were on the side of Loya's lacking the capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct.

But autism? That opinion shocked the District Attorney's office. In response, First Assistant District Attorney Brian Glenny, who by then had prosecuted 24 murder defendants on Cape Cod, asked Kelly to recommend a psychiatrist better suited to address autism.

Glenny found his super-expert in Judith Edersheim, a cofounder of the Center for Law, Brain, and Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital. She did not believe Loya was autistic or delusional. Further, Edersheim was the only expert witness to conclude that Loya was criminally responsible for the murder, but she arrived at her opinion without ever having met him. When Segadelli learned this, he denied Edersheim a visit with his client. When she finally did see him, it was from the stand, when she testified for the Commonwealth as its 26th and final witness.

Edersheim based her conclusion on Loya's writings, emails, and arrest report. She believed he suffered from two personality disorders, avoidant and borderline, but was not a loner and exhibited no psychotic symptoms. "He never had a break with reality," Edersheim testified, "There was a mountain of evidence that he knew what he was doing was wrong."

Two forensic expert witnesses for the Commonwealth and one for the defense all agreed that Loya suffered from mental illness. But each doctor had arrived at a different diagnosis.

If three expert witnesses couldn't reach a consensus, how could a jury determine whose opinion was most credible and accurate?

"An Asperger's diagnosis does not preclude depression or delusion, so it's not necessarily a different diagnosis but a partial one," says Katherine Ramsland, a professor of forensic psychology at DeSales University. "It's common to see widely differing opinions for violent criminals. A lot depends on the clinician's experience, position in the lineup of experts, expertise in a specific area."

After deliberating for three days, the jury found Loya guilty of first-degree murder with deliberate premeditation and extreme cruelty. He has since been transferred to a maximum-security facility, where he is serving a life sentence without parole. "I'm still effectively dead," Loya says. "I don't believe in the afterlife. And this is pretty much the Americanized idea of hell."

A Lost Cause?

Loya insists he consistently sought help from superiors, colleagues, and family, but was always met with some version of "get over it." Had he received treatment at the right time, Loya claims, the outcome might have been different. At Bridgewater, following his arrest, Loya participated in group therapy and took the antidepressant Prozac for about a year.

"Now I can see how horrible everything was," he says, "and how it could have just easily been fixed."

But while Loya went to his superiors and pursued therapy in Alaska, he stopped short of seeking treatment at the most critical time—when he was homicidal and plotting his revenge. Loya never sought counseling in Virginia, between late 2013, when he decided to kill Berlanga, and early 2015, when he did. Daignault's evaluation confirms this, stating that, in June 2014, Loya "wondered if he should abandon his plan and seek professional help, since he was planning to kill her and die while fighting the police. But he knew telling his story to a mental health professional would have been awkward, and he would probably have been immediately arrested."

"By that point," Loya now acknowledges, "I was a lost cause." "Instead of seeking out help to deal with the impulses that he had, he just followed through on them," Glenny says. "He knows it's wrong; he knows he could stop. But he doesn't like what the consequences might be, and goes through with it anyhow."

Loya's experience with treatment was limited to the nine therapy sessions in Alaska, months before he received the disciplinary report that unhinged him. Whether the Coast Guard should have done more to address Loya's mental health and stability was never addressed at trial.

"I think the Coast Guard owes Anna and Lisa a huge apology," Loya's father, George, says over the phone. "And they owe Adrian a huge apology."

"The biggest mistake I made with my son was I wouldn't listen to him when he had problems," he says in the emotional call. "Adrian's guilty. There's no doubt about it. But the question was always: Why? Something drove Adrian to be the man that he wasn't."

"It's kind of a scary thing to think, 'Was it us?'" Shirley says in a separate call. "Should I have fought harder to get him help earlier? I don't know. But it's a losing battle because it's all past." Daignault noted that Loya has likely had schizoid personality disorder since childhood, marked by social detachment and underachievement.

Though Loya still contends that Berlanga assaulted him, he now admits that he is not a victim of rape.

"Lisa never really did anything that bad to me, and it is because of how my mind is wired that her actions seemed horrible," he wrote in a follow-up letter from prison. "I now believe the [Coast Guard] in their own special way tried to help by not doing anything. They all knew if 'The Bad Night' got officially dealt with it would cause major problems to two good guardsmen. I escalated it because I was too stupid and naive to leave well enough alone. "And look what it got me."

Diagnoses Aplenty

Prosecution

Martin Kelly, M.D., forensic psychiatrist Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

In-person evaluation: 6 hours

Diagnosis: Asperger's syndrome

Criminally responsible: No

Judith Edersheim, M.D., forensic psychiatrist Cofounder, Center for Law, Brain, and Behavior; Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

In-person evaluation: 0 hours

Diagnosis: Avoidant personality and borderline personality disorders

Criminally responsible: Yes

Defense

John Daignault, Psy.D., forensic psychologist Part-time Instructor, Harvard Medical School

In-person evaluation: 48 hours

Diagnosis: Delusional disorder exacerbated by major depressive disorder; schizoid personality disorder

Criminally responsible: No