Anthropomorphism

Why Theological Waywardness Is Inevitable

Humans' natural cognitive proclivities beget theological incorrectness.

Posted August 17, 2016

A Conundrum about Prayer

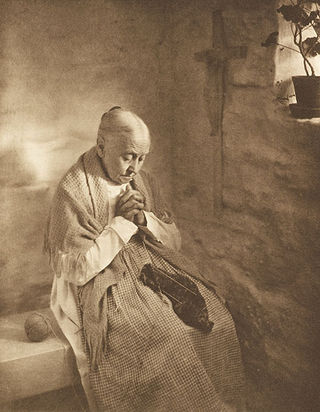

Religious skeptics have long noted various puzzles connected with praying. For example, why do people pray to a God whom they regard as all-knowing and, in particular, as already knowing everything there is to know about the contents of their own minds? In short, if God already knows what they are thinking, why do they need to take the time to tell God about these things?

Religions offer a variety of responses to such conundrums (such as “people should pray because God commands it!”) – responses that typically do not satisfy believers quite so much as they fail to satisfy the skeptics. Behind all of this, though, lurks an explanatory question that has intrigued cognitive scientists of religion. Why, on the face of it, do some of religious believers’ practices and statements not comport with the beliefs that they explicitly avow? Cognitive scientists of religion have labeled this phenomenon “theological incorrectness.”

Unconscious Cognitive Dispositions: Anthropomorphism

Cognitive scientists of religion have proposed that theological incorrectness arises from unconscious cognitive dispositions that shape people’s religious representations and reasoning on the fly. Probably the best known of these is human beings’ penchant for anthropomorphism. Humans impose human forms on everything from finding faces in the clouds to creating cartoon characters based on the shapes of the bottles for household products (Mr. Clean! Mrs. Butterworth!). A bit less conspicuously, perhaps, but no less frequently, humans exhibit psychological anthropomorphism, carrying on conversations with their cars, their computing devices, and myriad other objects that they must deal with in the course of a day.

This is no less true with humans’ representations and reflections about their gods. That only presents a problem, though, if the gods in question are those of religions (World Religions, Religions of the Book) that have theological traditions (not all religions do). In those cases participants also typically subscribe explicitly to the kinds of complicated, carefully formulated, theological articulations of doctrines (e.g., gods’ omniscience) that have been forged from decades and, sometimes, centuries of contentious debates. These doctrinal religions employ plentiful resources, from preaching, to printing catechisms, to running schools, and more, to instill these abstruse formulas in followers’ minds. Adherents often have various central doctrines and statements of faith memorized and can readily recite them.

Theological Incorrectness

In landmark papers in the cognitive science of religion, experimenters have found that religious participants’ religious representations and reasoning in implicit tasks, such as recalling narratives about gods that are consistent with their doctrinal understandings, routinely diverge from their overt protestations about their (explicit) beliefs. Their implicit cognitive processing reveals anthropomorphic representations and unconscious inferences about their gods that suggest that they resemble Superman, rather than the theologically correct conceptions the participants avow. This finding has been replicated across multiple religions in both large-scale and small-scale settings in America, India, and Brazil (at least).

It is worth noting that if these proclivities are, in fact, rooted in natural (but unconscious) cognitive inclinations, then theological incorrectness is unlikely to disappear. No one understands this any better than the clergy, part of whose job it is to police doctrinal waywardness.