Personality

What Is Luck?

Do life events happen to you or do you make them happen?

Posted July 16, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- People who believe in luck tend to see life events as something they don't directly control.

- Believing in luck can be a way to defend against the chaos of life.

2021 is shaping up to be another transformational year as we slowly emerge from the pandemic and try to get our lives back something resembling normal. Stories about people who were infected by the virus and survived are appearing in newspapers, magazines, and online. A recent article in Vox documents how some survivors of the pandemic have described feeling out of control and helpless in the face of the disease.[1]

And, sadly, many have also described feeling guilty for having survived when others didn’t. Survivors, as well as people who never got sick at all, often attribute their survival to luck. This made me wonder: Do people typically feel lucky they survived COVID-19 or unlucky to have been exposed to it? Deciding if one is lucky to have escaped or unlucky to have been affected in the first place can be a difficult thing to do. So what exactly is luck?

Defining luck

People who believe in luck describe themselves as either lucky or unlucky as if luck were a stable and enduring personality characteristic. However, researchers who study luck usually see it very differently.

Luck in psychology is usually thought of as an attribution. An attribution is a decision we make about the cause of an event or the reason for something happening in the world. Because we’re social animals, the “event” we’re focused on is very often other people. We are deeply invested in figuring out why people do what they do.

When we go looking for factors that cause an event, we tend to attribute causality to our own skill, our effort, the difficulty of the task or to luck. Skill and effort are internal, relatively stable, personal factors that can be controlled by the person doing the attributing. The difficulty of the task and luck are external to us, unstable and less controllable.

Attributions of luck

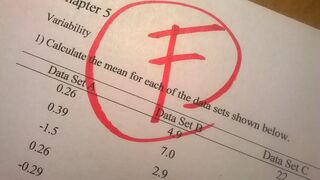

Imagine you’re a student, taking a course in something brand new to you—let’s say a course in statistics. You get the results of the first exam back and you see a large red "F" on the page. How do you explain the cause of this event? Researchers say that your attribution will focus on three basic features of the situation: the locus and stability of the cause, and the degree of control we have over that cause. The locus of a cause refers to whether we see the source of the cause as an aspect of our own personality and behavior (an internal locus) or as coming from the situation we are in (an external locus.) So, if you say to yourself, “I flunked the test because I blew it off and went out partying instead of studying,” that’s an internal attribution—an explanation based on an assessment of your own behavior.

If you then say, “I’ve always been a good student, I just have to apply myself next time,” then you see your internal attribution as a stable one. And, if you go on to say, “I can join the study group that was just organized on my dorm floor or go see the tutor for the class before the next exam,” then you’re saying that the cause of your poor grade on the first exam is internal, stable and that you have some control over it. This student is not likely to attribute his or her grade to luck.

Now imagine that your response to the poor grade on the exam is to say “Wow, the teacher really hates me! She graded my exam way too harshly. She was probably ticked off about something when she graded my exam—maybe next time she’ll be in a better mood.” Then your attribution is external (based on the situation, not on your own abilities), unstable and outside of your control. This student is much more likely to say that he or she flunked because of bad luck.

The attribution explanation of luck works in some situations, but it doesn’t work in all of them, and, worst of all, it doesn’t really match up with the way that most people talk about luck in daily life.

Two researchers in the Netherlands asked gamblers, a group of people who should be familiar with luck and being lucky, what they thought about luck.[2] To their surprise, not one gambler mentioned cause and effect relationships, or luck being something that was external or out of their control. On the contrary, the gamblers said that some people were just luckier than others (implying that luck is an internal characteristic of some people) and that luck was also something that existed out there in the universe somewhere, external and separate from humanity. The trick was to recognize when luck was available, and when it could be used, when you might get it to linger beside you by rubbing your lucky rabbits’ foot or using your lucky dice, and when luck was running out.

Luck has a multitude of definitions, varying not just across individuals but also across situations. Sometimes we see ourselves at the mercy of chance. Other times, we see luck almost as our birthright. We often believe in luck and in our own personal luckiness as a defense against the whims of fortune. Ascribing survival during the pandemic to luck is an example of this defense against randomness in the universe.

References

1] Courage, Katherine Harmon (March 17, 2021). “You can’t get away from the idea that you’re just lucky to be alive.” VOX, https://www.vox.com/22316006/covid-19-survivor-guilt-symptoms-mental-he…, Accessed July 10, 2021.

2] Wagenaar, W.A and Keren, G.B (1988). Chance and luck are not the same. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 1, 65-75.