Media

How Does Misinformation Spread Online?

Research explores the characteristics of the online "misinformation ecosystem."

Posted December 6, 2018 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Social media has reshaped how we consume news. A study by the Pew Research Center last year found that two-thirds of Americans reported getting their news from social media.

As most of us probably know, this is a double-edged sword. Obviously, it’s good to have diverse sources of news, and information can spread much faster on social media than it can through traditional top-down media, like television or newspapers—this is part of the reason for the popularity of new media!

The problem is that information on social media doesn’t have to be vetted, investigated, or confirmed in order to spread, and this leads to misinformation and unsubstantiated rumors spreading like wildfire online. In the past few years, the online misinformation ecosystem has developed: a large, decentralized web of “news” sources that plagiarize, jump to unwarranted conclusions, fail to vet sources adequately, or simply fabricate information.

This ecosystem consists of a variety of people and organizations that cultivate large followings on social media. Through sharing and cross-promotion, they amplify and spread bits of information that fit their particular worldview without fact-checking or basic due diligence. The actors that engage in this kind of practice create a massive, decentralized web of misinformation, one that traditional sources of news are hard-pressed to counteract.

In a recent paper, I examined the spread of conspiracy theories about the Zika virus on Twitter. These conspiracy theories, popular around the time of the 2015-16 outbreak in Latin America, mostly alleged that the microcephaly cases attributed to the virus were really caused by something else and that Zika was essentially being scapegoated in a coverup by governments, NGOs, and the pharmaceutical industry. Worryingly, these theories tended to place the blame on things like vaccines, pesticides, and genetically modified sterile mosquitoes, all of which are important weapons in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases like Zika. These were not just idle rumors, but actively harmful misinformation.

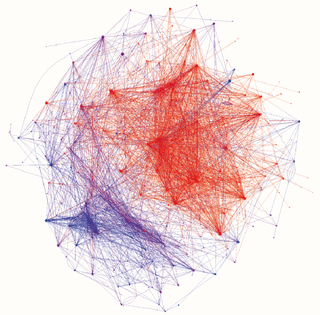

The graph presented here shows the pattern made by tens of thousands of tweets and retweets about the conspiracy theories: Individual dots (some of which are difficult to see at this scale) are accounts, and the lines between the dots represent one account retweeting another.

The lines and dots are colored according to whether the accounts mostly advocated or debunked the conspiracy theories. The red network represents the activity of the “misinformation ecosystem” on Zika: a massive (and massively interconnected) conglomeration of click-generating nonsense, with rumors about Zika spreading through it like the virus itself.

The blue network represents the efforts of Twitter users to debunk the rumors. It’s more centralized—it’s organized around fact-checkers like PolitiFact—and it’s much smaller. This is a dramatic illustration of the old saying that a lie can make it halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its boots on.

Unfortunately, I’ve seen a variation of this happen firsthand. My co-author Karen Douglas and I published an article describing a study on the psychology of the 9/11 conspiracy theories back in 2013. It didn't see much discussion until a website picked it up and ran with a misinterpretation of the study that flattered a certain audience.

This rumor started tearing around the Internet despite our efforts to contain it. We posted rebuttals and refutations, explaining how this conclusion was based on a misreading of the article, but it didn’t do much to stem the tide. Five years later, that misinterpretation of this old article is still bouncing around the misinformation ecosystem.

These are just two examples—there are new rumors every day, and the online rumor mill grinds on. Social media companies are increasingly aware of this problem and are taking steps to curb the spread of misinformation. In the meantime, our best defense is to educate ourselves about media and to get into the habit of thinking critically and carefully, even—or especially—about stories that we desperately want to believe.

References

Shearer, E., & Gottfried, J. (2017, September 7). News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2017. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platf…

Starbird, K., Arif, A., Wilson, T., Koevering, K. Van, Yefimova, K., & Scarnecchia, D. P. (2018). Ecosystem or Echo-System ? Exploring content sharing across alternative media domains. In 12th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM) (pp. 365–374). Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/kstarbi/Starbird-et-al-ICWSM-2018-Echosys…

Wood, M. J. (2018). Propagating and Debunking donspiracy theories on Twitter during the 2015–2016 Zika virus outbreak. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21, 485-490. http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0669

Wood, M. J., & Douglas, K. M. (2013). “What about building 7?" A social psychological study of online discussion of 9/11 conspiracy theories. Frontiers in Psychology, 4:409. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00409