Personality

Regional Differences in Personality: Surprising Findings

Geographic differences in personality traits matter, but in unexpected ways

Posted June 28, 2015

It is well-known that many important societal indicators, that is, political, economic, social, and health factors vary across geographical regions. Many of these same indicators are also known to vary at the individual level depending on differences in one’s personality. For example, people high in conscientiousness tend to have better health, people high in openness to experience tend to be more politically liberal, while those who are more neurotic tend to have poorer mental health, and so on. Linking these two fields together, some researchers have begun to investigate whether geographic differences in the distribution of personality traits are related to these same outcomes. The results are somewhat surprising. Regional variations in personality traits have been linked to differences in societal outcomes, but some of these relationships turn out to be the opposite of what would be expected from the relationships found at the individual level. Additionally, personality traits at the geographic level correlate with each other in a very different pattern from that seen at the individual level.

A number of studies in recent times, one in the United Kingdom (Rentfrow, Jokela, & Lamb, 2015) and others in the USA (Rentfrow et al., 2013; Rentfrow, Gosling, & Potter, 2008; Rentfrow, Mellander, & Florida, 2009), looked at geographical differences in the Big Five personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and found that these were related to regional differences in political, economic, social, and health (PESH) indicators. The relationships between personality traits at the regional level with PESH indicators was similar in some respects to the relationship of individual personality traits to these same indicators but quite different in other respects. For example, in the United Kingdom regions with high levels of conscientiousness tended to vote more often for conservative political candidates, while regions with high levels of openness to experience tended to vote more often for liberal political candidates (specifically the Liberal Democrat party). This is in line with personality-related political preferences at the individual level. Similarly, individuals who are high in conscientiousness and low in neuroticism tend to have better overall health, and in the UK regions with high levels of conscientiousness (as well as higher extraversion) and lower levels of neuroticism also tended to have better health indicators, such as longer life expectancy, fewer long-term health problems and lower rates of death from heart disease, cancer and stroke. However, oddly enough, a study in the USA found that states with higher levels of conscientiousness actually had lower life expectancy compared to less conscientious states, although higher neuroticism was associated with poorer health as expected (Rentfrow, et al., 2008). At the individual level, higher conscientiousness tends to be associated with higher occupational status and to some extent with higher income (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999), but this is quite different from what is found at the regional level. In the UK median regional incomes are associated with lower conscientiousness. Similarly, in the USA, states with higher levels of conscientiousness also tend to have a lower gross state product.[1]

Looking at the way personality traits cluster together and the pattern of how they are correlated with each other also reveals some unusual findings. At the individual level, the Big Five traits tend to correlate with each other in a predictable socially desirable pattern. That is, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience tend to be all positively correlated with each other, and all are negatively correlated with neuroticism. As I have discussed in a previous post, this has led some scholars to think that there is a general factor of personality (GFP) underlying the Big Five consisting of co-varying socially desirable traits. Whether or not the GFP represents a substantive feature of personality or is merely a statistical artefact is still being debated (Davies, Connelly, Ones, & Birkland, 2015). Recently, it has been suggested that there might be a GFP that applies at the level of national differences in personality traits (Dunkel, Stolarski, van der Linden, & Fernandes, 2014). However, when Dunkel et al. attempted to derive a GFP from nationally aggregated self-report data from 33 countries, the result was a factor comprised of high extraversion, openness to experience and neuroticism, and low agreeableness and conscientiousness. This is quite strikingly different from an individual level GFP which involves a combination of high agreeableness and conscientiousness and low neuroticism.[2] The latter three components are considered quite important features of a mature, stable personality so it seems rather odd that personality traits would form the opposite pattern at a national level. The studies in the UK and the USA show similar anomalies. In the UK study for example, the authors report correlations between the Big Five at both individual and regional levels. At the individual level, the Big Five correlate with each other in the expected socially desirable way. However, at the regional level, they show a different pattern, as extraversion is negatively correlated with agreeableness, while openness to experience is negatively correlated with both agreeableness and conscientiousness. Most of the other correlations are more in line with the individual pattern though, e.g. neuroticism has negative correlations with all the other traits, and agreeableness and conscientiousness have strong positive correlations with each other, and extraversion and openness to experience are also positively correlated. These regional level correlations manifest in noticeable geographical clusters of traits. For example, London is notable for showing a pattern of high levels of extraversion and openness to experience, and also low levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness. Most areas of Scotland on the other hand shows a contrasting pattern of noticeable introversion, high agreeableness, low neuroticism and the Scottish highlands in particular had high levels of conscientiousness. Much of Wales was striking for having high levels of neuroticism and introversion, high openness to experience in some areas, and low levels of conscientiousness. Based on these patterns, it appears that people in London are disproportionately outgoing, unconventional, excitement-seeking, impulsive and self-centred. People in much of Scotland on the other hand are more likely to be quiet and reserved, yet friendly and cooperative, as well as calm and emotionally stable. Those in the Highlands in particular are also more likely to be self-disciplined, hardworking and reliable. The people of Wales appear to have a rather troubling pattern in that they are disproportionately likely to be anxious and depressed, socially reserved, undisciplined, and in some areas rather unconventional.

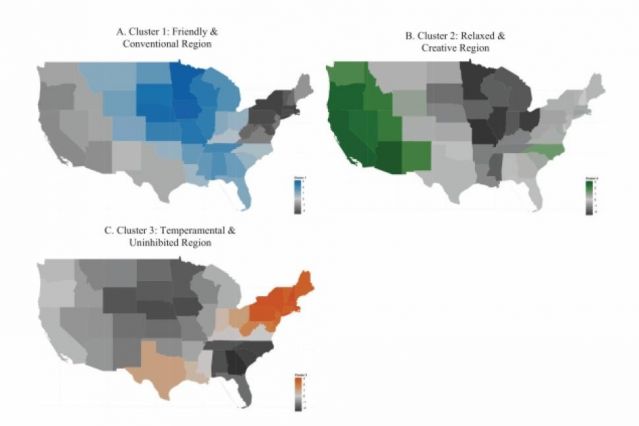

In the USA, personality traits aggregated at the state level show quite a different pattern of correlations from those in the UK.[3] For example, extraversion is positively correlated with both agreeableness and conscientiousness, is uncorrelated with neuroticism and surprisingly has a strong negative correlation with openness to experience which is the opposite of the usual pattern. Agreeableness and conscientiousness have a strong positive correlation with each other, just like in the UK. Another study in the USA (Rentfrow, et al., 2013) identified three distinct personality clusters. The first one was a ‘friendly and conventional’ cluster predominantly in the north central Great Plains and in the South characterised by moderately high extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, lower neuroticism, and quite low openness to experience. The second cluster called ‘relaxed and creative’, predominantly in the West and in some states along the eastern seaboard, was characterised by very high openness to experience, and fairly low extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism, and average conscientiousness. The third cluster called ‘temperamental and uninhibited’, predominantly in states in New England and the Middle Atlantic, and was characterised by very high neuroticism, moderately high openness to experience, very low conscientiousness, and moderately low extraversion and agreeableness. Not surprisingly, the friendly and conventional cluster was most politically conservative, which is consistent with higher conscientiousness and lower openness to experience. Conversely, the other two clusters, which were low in conscientiousness and higher in openness to experience tended to be more politically liberal. However, the other PESH indicators of these three clusters were rather more surprising. For example, the friendly and conventional cluster would seem to have a generally healthy profile, as higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness, and lower levels of neuroticism tend to be associated with general health and well-being, as well as productivity at the individual level. Consistent with their friendly outlook, these states did tend to have higher levels of social capital. However, they also tended to be economically poorer, have lower human capital, and poorer health behavior, and were more socially intolerant. Looking at the temperamental and uninhibited cluster, one might expect them to have the most disturbed PESH indicators, as they showed the highest levels of neuroticism and the lowest levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness, but they actually do rather well in some respects. States in this cluster tended to be wealthier and to have more human capital, while inclusion in this cluster was unrelated to violent crime, health behavior or measures of well-being. States in the relaxed and creative cluster had somewhat mixed outcomes. They enjoyed higher levels of well-being and had better health behavior (which seems consistent with their low levels of neuroticism) and had the highest levels of wealth, human capital, and social tolerance, but tended to have poorer social capital and more violent crime. Interestingly, these states were the most strongly associated with innovation, which seems consistent with their high levels of openness to experience.

A couple of points stand out for me regarding the way personality traits are distributed in the UK and the USA respectively. Firstly, none of the patterns observed are consistent with a general factor of personality that combines all the Big Five traits in a socially desirable way. In the UK for example, one of the geographic patterns that emerges is that high extraversion tends to be associated with low agreeableness and vice versa. Relatedly, median incomes were positively associated with extraversion and negatively associated with agreeableness as well. In terms of interpersonal behavior, a combination of high extraversion and low agreeableness tends to be associated with self-assertiveness and the desire to be socially dominant, while a combination of low extraversion and high agreeableness tends to be associated with being very accommodating of others and a desire to get along with people. Perhaps this suggests that communities in Britain tend to vary noticeably along a continuum of dominance versus submissiveness that is also associated with income, so that in wealthier communities such as London people tend to be predominantly very competitive and self-seeking, whereas in less prosperous communities they tend to be more concerned about the welfare of others. Perhaps a vibrant cosmopolitan city like London might be most attractive to people who are outgoing, artistic, and desiring immediate gratification, yet more sedate communities might be more welcoming of people with a more communal orientation. The USA shows a different pattern, as the friendly conventional cluster was both extraverted and agreeable yet lower in openness to experience, while the other two clusters were each more introverted and disagreeable, but higher in openness to experience, and yet also were wealthier. Additionally, gross state product in the USA is negatively correlated with both agreeableness and conscientiousness. The USA appears to have a different interpersonal pattern from the UK in that states tend to vary along a continuum from being warm, friendly and conventional (i.e. extraverted and agreeable, but low in openness) at one end to being more cold and aloof and more individualistic at the other, rather than along a continuum of interpersonal dominance versus submissiveness. Perhaps this reflects an opposition between the desire to form cohesive social bonds through conformity to tradition versus the desire to go one’s own way and express one’s individuality. Possibly, in the USA there are better economic opportunities for people with a highly individualistic orientation compared to more conventional communally-oriented people. Taken together, these findings seem to suggest that at a geographical level, personality traits do not seem to combine together into a coherent general factor of personality that varies along a single socially desirable dimension. This might be because the Big Five traits each have their costs as well as benefits, and no single combination of these traits is necessarily optimal across different social environments.

The other point that stands out for me is that the idea that the character of a community depends largely on the character of the individuals who compose it does not seem to be completely true. Some scholars have seriously argued that the outcomes a society experiences directly reflect the individual traits of its members (e.g. Lynn & Vanhanen, 2002, cited in Stolarski, Zajenkowski, & Meisenberg, 2013). However, this view has been criticised as representing an ecological fallacy as it is not necessarily the case that findings at the individual level apply at the societal level, and vice versa because the individual and societal levels are logically independent. In practice, the two levels are often connected, but it may be naïve to expect correlates at one level to apply to the other level (Mõttus, Allik, & Realo, 2010). The reasons why individual and societal level correlates do not always match are not entirely clear, and are likely to be complex. Perhaps one important contributor is that individuals do not have much control over large-scale factors that influence a society as a whole. Take the example of the negative correlation between state-level conscientiousness and life expectancy in the USA. It could be that life is objectively more hazardous in some states than in others, and that people living in hazardous areas have adapted by becoming more cautious and careful. Similarly, in regard to interpersonal traits, at the individual level a combination of high extraversion and agreeableness might be socially desirable as these people tend to be more popular. However, due to economic factors in some countries there might be financial incentives for people who are extraverted and disagreeable to seek high status jobs in prosperous regions, while those who are introverted and agreeable might fit in better in less prosperous but perhaps more socially cohesive neighbourhoods.

In conclusion, it seems that personality does matter at the societal level, possibly as much as it does at the individual level. However, the individual and the societal levels are quite distinct, perhaps because they are influenced by quite different factors. More research is needed to understand the complex factors that underlie these relationships.

Footnotes

[1] I obtained this result by correlating state-level personality trait means from Rentfrow et al. (2008) with state-level economic data from McDaniel (2006). The negative correlation was significant, r = -.37, p < .01.

[2] They also derived a national-level GFP from other-reported traits (i.e. respondents reported on the traits of a person they know well) and this actually was consistent with an individual-level GFP though.

[3] Rentfrow et al. (2008) provide state-level means for each of the Big Five traits, but no data on their inter-correlations, so I calculated the latter myself. The coefficients can be viewed in this spreadsheet.

Image Credits

Map of Big Five in Great Britain via The Independent, from maps in Rentfrow , Jokela, & Lamb (2015).

Personality trait clusters in the USA via NY Daily News from maps in Rentfrow, Medlander, & Florida (2009).

Please consider following me on Facebook, Google Plus, or Twitter.

© Scott McGreal. Please do not reproduce without permission. Brief excerpts may be quoted as long as a link to the original article is provided.

Other Posts concerning the General factor of personality

Personality’s “Big One”: Reality or Artifact?

Personality’s Big One Revisited: The Allure of the Dark Side

What Is An Intelligent Personality?

Do Personality Traits and Values Form a Coherent Whole?

Who Uses their Head and Who Listens to their Heart?

References

Davies, S. E., Connelly, B. S., Ones, D. S., & Birkland, A. S. (2015). The General Factor of Personality: The “Big One,” a self-evaluative trait, or a methodological gnat that won’t go away? Personality and Individual Differences, 81(0), 13-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.006

Dunkel, C. S., Stolarski, M., van der Linden, D., & Fernandes, H. B. F. (2014). A reanalysis of national intelligence and personality: The role of the general factor of personality. Intelligence, 47(0), 188-193. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.09.012

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999). The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52(3), 621-652. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00174.x

Lynn, R., & Vanhanen, T. (2002). IQ and the wealth of nations. Westport, CT: Praeger.

McDaniel, M. A. (2006). Estimating state IQ: Measurement challenges and preliminary correlates. Intelligence, 34(6), 607-619. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.08.007

Mõttus, R., Allik, J., & Realo, A. (2010). An attempt to validate national mean scores of Conscientiousness: No necessarily paradoxical findings. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(5), 630-640. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.08.005

Rentfrow, P. J., Gosling, S. D., Jokela, M., Stillwell, D. J., Kosinski, M., & Potter, J. (2013). Divided we stand: Three psychological regions of the United States and their political, economic, social, and health correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 996-1012. doi: 10.1037/a0034434

Rentfrow, P. J., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). A Theory of the Emergence, Persistence, and Expression of Geographic Variation in Psychological Characteristics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 339-369. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00084.x

Rentfrow, P. J., Jokela, M., & Lamb, M. E. (2015). Regional Personality Differences in Great Britain. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0122245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122245

Rentfrow, P. J., Mellander, C., & Florida, R. (2009). Happy States of America: A state-level analysis of psychological, economic, and social well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 1073-1082. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.08.005

Stolarski, M., Zajenkowski, M., & Meisenberg, G. (2013). National intelligence and personality: Their relationships and impact on national economic success. Intelligence, 41(2), 94-101. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2012.11.003