Career

Woody Allen's Apropos of Nothing: A Legacy

Part Two: Allen's denials extend to his problems with women.

Posted June 29, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

In his memoir, Woody writes that he grew up enjoying women. But he says he strove to enhance his dating appeal by belatedly educating himself in literature, art, and philosophy.

His early successes in gag writing, stand-up comedy, and filmmaking made many beautiful, accomplished women available to him.

But the psychoanalytic maven (who helped popularize psychotherapy from the 1950s on) denies having had insight into clear warning signs of incompatibility with the women in his life.

He wed his first wife, Harlene, when he was starting his rapid career rise, while she was beginning college. But Woody says he was blind to their clashing lifestyles.

He denies having realized that his gorgeous second wife, Louise Lasser, had serious emotional problems.

Woody's pleas of Not Guilty crescendo about halfway through his book, when he discusses his long, non-live-in, unwed relationship with the beautiful, sophisticated Mia Farrow.

He again denies having noticed many warning signs. These range from Mia’s large collection of children—seven when they met—to abundant mental instability in her family (drinking, a brother’s suicide, another in prison for sexual abuse).

Woody also says he was shocked by her early, impulsive statement that she’d like to have his baby.

Though disinterested in most of Mia’s children, and notwithstanding the ebbing of their passion, and the fading of their relationship into one of convenience, he reluctantly endorsed the idea.

When their procreative efforts failed, he acceded to Mia’s desire to adopt.

And suddenly, Woody turned doting father of new baby Dylan. Fussing over cute, part-Korean-born Moses and his adored Dylan, he spent increasing time in Mia’s summer house and her apartment.

Then Mia gets pregnant. Only the event, far from enhancing Woody and Mia's relationship, furthers their estrangement.

While Woody doesn’t list more denials, he omits some key issues revealed in their custody trial.

He writes that he found Mia’s desire to breastfeed Ronan for four or more years bizarre and that he worried lest her intense relationship with the baby would negatively impact Dylan.

But he fails to mention Mia’s concern that Woody’s relationship with Dylan was too intense.

He says that both children were seeing therapists by the time Ronan was around 2, But he fails to note that he and Mia were themselves in therapy for their respective parenting problems.

Nor does he describe the conflicted relationship between him and Ronan, which testimony showed had begun early, with Ronan, even as an infant, kicking at Woody and crying in his presence.

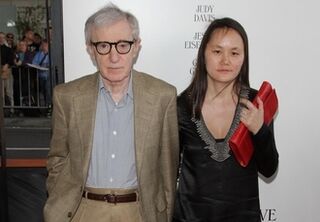

And then Soon-Yi crashes into his life and Woody’s Not Guilty plea becomes central to his narrative.

He denies that his infamous-seeming statement, "the heart wants what it wants," implying that it can also take what it wants, originated with him. Instead, he attributes the saying to Saul Bellow and Emily Dickinson.

He adds that as a young girl, Soon-Yi actually disliked him.

Woody also reprises many previous denials of his guilt by himself and others,

In addition, he voices his grief over the loss of his children thanks to the custody trial's pro-Mia judge.

He repeatedly stresses his innocence, reminding readers that he was not just cleared of child abuse in two lengthy investigations but that he has never been charged with any offense,

Quoting his lately reconciled son, Moses, and Soon-Yi, Woody also discusses Mia’s flawed parenting.

Examples include Mia’s favoring her biological children over her adopted ones, and her brainwashing of all the children into lifelong hatred of Woody.

He also mentions Mia's impatience and fierce temper, and at times disastrous results, such as the suicides of two of her grown, adopted children.

Most harrowing is his description of Mia’s insistence—based on her rationale that "you need to be tall to go into politics"—that as a young adult Ronan undergo excruciating surgery to lengthen his legs.

The operations, which involved breaking Ronan's legs several times, subjected him to a long and painful recovery.

I found most of this account, laced with humorous anecdotes, persuasive. I also accepted Woody’s justification of his affair with Soon-Yi by his repeated reminders that the relationship has lasted and flourished; they've even adopted and lovingly raised two seeming well adjusted college-aged daughters.

But given his and Mia's strife-ridden relationship, I didn't totally buy Woody's denial of anger or other underlying motives for why he failed to hide from Mia the nude Soon-Yi photos that revealed the affair ("sometimes a cigar is just a blunder by a klutz.")

I also felt chilled by the near-clinical tone in which he writes that he understood that Mia’s reaction of "shock, dismay, rage, everything," on learning of the affair, “was the correct one.“

And I wondered why he never questions his implied assumption that it’s fine to have affairs with the sisters of two his lovers—both of Diane Keaton’s, and at least one of Mia’s.

Today, Woody’s career seems effectively ruined by Mia and her two avenging children, Dylan and Ronan.

His film, A Rainy Day in New York, is a big hit in Europe. But U.S. filmgoers will not see it—unless they opt to fly again, where they may, if lucky, catch a screening on American Airlines.

Similarly, his latest comedy, Rifkin's Festival, is scheduled to open in Spain this fall, but it too may not open in America.

I was most saddened by Woody’s repeated denials that he cares about his legacy, however, blemished.

He stresses that his happy home life has left him a contented man. But I find it heartbreaking that #Me Too and other forces are managing to obliterate this unique, sensitive, and prolific, if quirky, artist from cinematic history.

However, film historian and author of the pending The Cinephile's Guide to the Great Age of Cinema, Max Alvarez, recently told me that Woody Allen's legacy is lasting.

He brought Jewish humor from vaudeville into mainstream commercial filmmaking.

He is, added Alvarez, an important Hollywood director who, "though shunning intellectual labels himself, was not afraid to showcase intellectual and cultural content in his films," even if much of his audience found many references incomprehensible.

On Amazon, I was heartened to see that many readers have bought and read Apropos of Nothing because they still admit to being fans.

Would this please Woody? I hope so. Because I still hope to see more of his films.