Narcissism

The Saviors of Their Peoples

A narcissistic, grandiose self-image often fuels the tyrant’s messiah complex.

Posted May 1, 2019

- “They love me all,” Muammar Gaddafi insisted before he was overthrown. “They will die to protect me . . . my people.”

- When presented with an ultimatum to leave Iraq or be invaded by the United States, Saddam Hussein approved a demonstration. Demonstrators waved portraits of their tyrant and carried banners that proclaimed: “Saddam is Iraq and Iraq is Saddam.” Saddam approved the message. Otherwise, it would never have been delivered.

- Mao Zedong was “the savior of the people,” according to Chinese Communist propaganda, over which he had control.

- Josef Stalin’s “messianic egotism was boundless,” his biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore concluded.

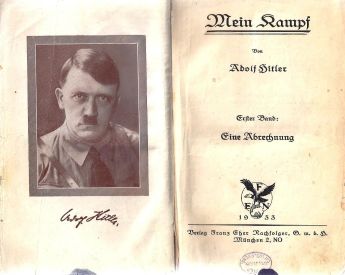

- And Adolf Hitler told readers of Mein Kampf that he believed he was “acting in accordance with the will of the Almighty Creator... .”

Psychoanalyst Walter Langer was convinced that Hitler had a “messiah complex.” He came to this conclusion after noting that the Nazi tyrant repeatedly asserted that he was chosen by Providence to rescue the German people from the ignominy of defeat in World War I, from the “threat” posed by Jews and Bolsheviks, and from the hardships of economic failure. Of all the psychological traits and aspects of Hitler’s mental health he speculated about, Langer considered the Führer’s messiah complex to be his “most outstanding characteristic.”

“. . . Fate itself puts forward many for selection,” Hitler asserted in his memoir, “and then ultimately, in the free play of forces, gives victory to the stronger and more competent, entrusting him with the solution of the problem.”

Dry, rant-filled and turgid, Mein Kampf nevertheless holds valuable information for anyone seeking to understand the mind of some tyrannical personalities.

While tyrants often share similar dark traits--including psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and malignant narcissism, as well as elements of paranoia and sadism--a belief that they are somehow chosen to dominate their countrymen and women seems to be a non-negotiable requirement for the position. In this sense, the messiah complex is not associated with a psychotic delusion that one is, in fact, a Christ-like figure. Rather, it appears to be more closely related to the extremely grandiose self-image characteristic of highly narcissistic individuals.

Of course, belief in ones’ own specialness is not limited to tyrants. To achieve the rank of tyrant, you must have either high intelligence or a subtype of it: “street smarts.” Both is best. You also need opportunity provided by social discontent and unrest. And you need remorseless brutality.

Combined with psychopathic ruthlessness and other dark traits, high intelligence seems to be correlated with a tyrant’s longevity. Consider Mao’s 41 years in power and Stalin’s 24 years.

Stalin lasted this long due in large part to his savvy understanding of what was required of him and his willingness to eliminate any real or suspected threats. In Stalin, The Court of the Red Tsar, Montefiore recounts an occurrence that indicates Stalin was well-aware of what he had to do to stay in power. Artyom Sergeev, Stalin’s adopted son, heard Stalin reprimand his notably less competent son, Vasily, for taking advantage of the name Stalin. Vasily protested that he was also a Stalin. “No, you’re not,” his father said. “You’re not Stalin and I’m not Stalin. Stalin is Soviet power. Stalin is what is in the newspapers and the portraits, not you, not even me!”

Although both Stalin and Hitler shared the belief that they were meant to rule, accounts like this attest to Stalin’s greater savviness and help explain why he lasted more than twice as long as his far more emotional Nazi opponent, who overestimated his own competence as a military commander and leader.

Street smarts alone combined with excessive brutality may limit a tyrant’s years at the top. The murderous and buffoonish Ugandan dictator Idi Amin should have learned this after eight years in power. He was chased out of Uganda by a combination of Ugandan and Tanzanian forces after ruining his county’s economy and terrorizing its population.

Muammar Qadhafi lasted 42 years. The limitations of his personality became apparent, however, when he faced serious internal and external threats: a rebellion by his people who were assisted by Western air power. His ego could not allow him to realize the serious threat he faced during the uprising. “My people love me,” he told an interviewer, “they would die to protect me.” It was his last interview. He would soon be found hiding in a drain pipe from which he would be pulled out and later murdered.

Tyrants’ antisocial and other personality disorders often contribute to their failings, particularly toward the end of their years in power. Stalin’s paranoia, a common and often, if not too extreme, useful feature of a tyrant’s personality, seemed to become more serious toward the end of his life. But these men were not psychotic; they were not legally insane. Their belief that they had a “right” to rule might be attributed to Providence, fate, innate ability and circumstance, or some combination of those reasons, but in the end, it can most probably be attributed to their extreme narcissism.

Anytime a leader declares that he or she alone has the ability to fix a nation’s problems, those who the hear the words should remember where others who believed they had such unique abilities have led their nations. In a democracy, it would not be surprising if many, if not most, leaders felt they were the best person at the time to lead. But to claim that they are the only one entrusted “with the solution to the problem” would too closely evoke the messiah complex in a narcissistic individual.

References

Montefiore, S. S. (2003). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 6

Efron, S. and Rotella, S. "Inside the Mind of a Dictator," Los Angeles Times, October 12, 2002.

"Iraq Rejects US Demand That Hussein Leave," Associated Press, March 18, 2003, reprinted by Global Policy Forum.

Hitler, A., (1925, 1943). Mein Kampf. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company) p. 510.

Haycock, D. A. (2019). Tyrannical Minds, Psychological Profiling, Narcissism and Dictatorship. New York: Pegasus Books.

Amanpour, C. “Gaddafi: Death of a Dictator,” ABCNews.com, accessed March 11, 2018.