OCD

OCD: A Sufferer's Take on the “Doubting Disorder”

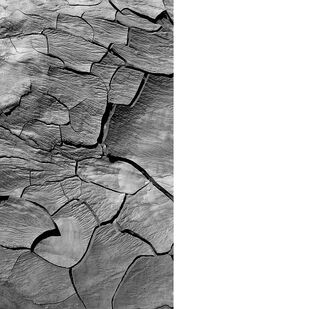

OCD seeks out and exploits the cracks in our realities.

Posted May 4, 2012

OCD is called the “doubting disorder,” at least among people inclined to give cutesy alliterative nicknames to mental illness. OCD is the pathological intolerance of risk, however minute, and the surrender to protective ritual, however unbearable.

No matter how unlikely a feared consequence, if there exists even the fraction of a percent of a possibility that it could occur, the disorder is able to find purchase. It seeks out the cracks in our perception of reality, it finds the tiny darkened territories on our internal maps; and then ceaselessly, tirelessly, it sets about expanding them.

These cartographic elaborations are careful and clever. You will not notice that anything has been changed until the ink starts to bleed through onto your hands, and then suddenly every inch of territory has been marked inaccessible. Everything made unknown and unsafe. Here there be dragons.

OCD presents itself as an innocuous problem-solving mechanism. If you have a problem, after all, you should try to find an answer. If there is danger, you should protect yourself. So when you are confronted with the possibility of an undesirable occurrence, the disorder suggests modes of defense. Its voice is like that of a beloved grandmother, recently passed away and resurrected by evil ritual. It is maternal, condescending, and affectionate, with a slight suggestion of righteous indignation. “I know what’s best for you dear,” it says, a hint of formaldehyde on its breath, a tiny fly crawling on its unblinking painted eye.

You listen compelled by guilt and fear, despite the suspicion that this cannot end well.

The disorder promises what it does not have the power to give. As you accept its reasoning, as you begin to work with it, it tightens its hold on you. It exaggerates danger and then offers a modicum of relief through an ever-expanding web of regulation and restriction.

OCD insinuates itself delicately until you are utterly constrained, until every moment of existence is a choice between submission to the rule of an absurd tyrant and absolute terror. Eventually the behavior of the sufferer is entirely divorced from reality. Hand washing is no longer a basic hygienic practice but a magic charm, a banishment cast against the immaterial, malevolent threat of “germs.”

Strange trigonometries are calculated and then arbitrarily discarded at the disorder’s whim. The world is perceived through a fine mesh of obsession. Everything is connected; everything shines like a razor with terrible significance.

OCD demands safety and certainty, and the fact that nothing can ever really be proven is regrettable but irrelevant to its purposes. It is the anti-life equation, and it will demonstrate to you, if you allow it, that free will is illusory and that everything wants you dead. It wants life to become a chessboard and then for all of the black squares to be systematically removed. It wants the world to be as small as a room and then small as your head and then even smaller than that.

As an OCD sufferer, I did any number of asinine, irrational things not because they would protect me, but because I thought they might, and I’d be darned if the one night I failed to properly pray the lord my soul to keep was the night I died before I woke.

Copyright, Fletcher Wortmann, 2012.

Author of Triggered: A Memoir of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (St. Martin’s Press), named one of Booklist’s “Top 10 Science & Health Books of 2012”.

Read my Psychology Today blog: Triggered