Psychology

A Crucial Overlooked Scientific Problem Is Lying in Plain Sight

The problem of psychology should be as well-known as quantum gravity.

Posted August 19, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Everyone who is familiar with 20th-century physics knows that the Newtonian classic "matter in motion" paradigm was overturned by the "twin pillars" of quantum mechanics and general relativity. It is also well-known that these two theories offer very different pictures and mathematical languages for describing the material universe. This results in one of the greatest problems in all of science, which can be stated as follows: Can these two pillars of physics be coherently merged into a theory of quantum gravity? This is the much-vaunted “theory of everything,” and it has so captured the popular imagination that hundreds of books, courses, and even movies have been made about it.

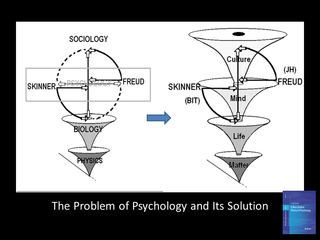

I have long argued that a similar problem besets psychology. And I believe it is of an even greater magnitude in terms of its implication for our understanding of ourselves and how we should live in the 21st century. Sometimes called "the crisis" (as Lev Vygotsky labeled it back in 1927), I have rechristened it “the problem of psychology”. Much like the problem of quantum gravity, the problem of psychology can be stated simply: Why, up until this point, has it been it impossible to have a clear way to develop consensus among the experts on how we define the science of mind and behavior?

It does not seem as though it should be that hard to solve. But it is.

As with quantum gravity, the problem of psychology is well-known, at least to theoretical psychologists. Indeed, if there is one thing upon which theoretical psychologists agree it is that there is no consensus about how to define what psychology is. But the problem of psychology is not well-known by the public. I find this fascinating. To me, it should be even more interesting to the lay public than the problem of quantum gravity. However, it is not widely talked about, and I am not aware of any movies about it.

To see the problem, just open any Psychology 101 textbook, and there it is. Of course, the textbook will not say right off the bat that there is a profound problem with the field in that the experts cannot agree on what is meant by the joint intersection of the concepts of "science," "mind," and "behavior." In fact, virtually all textbooks seem to follow the same basic pattern. They begin with some story of either of some everyday encounter or some really remarkable human phenomena and then proceed to proclaim how interesting human behavior is and how important it is to study it scientifically. Then they have a brief section on “What is psychology?” in which the text defines the field as the science of (a) mind; (b) behavior; or (c) both, with the combination of the two being the most common.

And there it is. This is the core of what you need to know to understand the problem of psychology. Lying right there, out in the open, for all to see.

Textbook knowledge refers to the foundational consensus of the experts in the field. And this empirical fact shows with certainty that the experts in psychology cannot even agree on whether the discipline is a science about "mind," "behavior," or some combination. This has serious implications: It means that if the experts cannot agree on that, then the knowledge that follows is going to be suspect or at least fuzzy because it is not anchored to a coherent system of understanding. (Here is a recent academic article that confirms this point.)

It seems to me that the problem of psychology should be at least as well-known as the problem of quantum gravity. After all, although I understand that quantum mechanics and general relativity are crucial in things like my cell phone’s GPS system, it is also the case that these worlds are quite remote from everyday experience. In addition, it is hard for me to see the relevance of these theories for things like the meaning of life or understanding the relationship I have with my wife and kids. Yet what could be more familiar and relevant to everyday experience than the concepts of mind and behavior? Shouldn't the public find it fascinating that we experts know that these concepts cannot be defined with any consensus? I think they should make a movie about that.

For more on the problem of psychology, and educational videos on its possible solution from the vantage point of the Unified Theory, see here, and specifically here.