Suicide

Why Do Suicidal People Not Seek Help?

Half of people who die by suicide do not seek help.

Updated February 21, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- In a severe emotional crisis, we may be unable to see a solution; suicide then appears as a possible way out.

- Many people with suicidal ideation do not think this is a reason to seek help.

- A recent study proposes a distress-processing model for individuals experiencing suicidal thoughts.

Each year, thousands of people die by suicide because they do not think that they need medical treatment or that a doctor’s office or a mental health center is the right address to get help. This is particularly pertinent with the young, where a study found that two-thirds did not seek help within a month before their suicide (1).

What I learned from hundreds of interviews with people who had attempted suicide.

In an early study (2), we asked people one year after a suicide attempt which could have stopped them from harming themselves. To our surprise, 52 percent said “nobody.” Twenty-one percent mentioned relatives or friends, and only 10 percent mentioned a health professional. Fifty percent said that they could not have accepted help. My interpretation of these results was that suicidal people experience suicide as ego-syntonic, that is, as something that makes sense to them personally and that does not need treatment.

Another reason for not seeking help is shame, particularly in the young. The authors of a Swedish study (3) interviewed parents of 33 boys and adolescents who had died by suicide. Shame was found to be the most frequent reason for the suicide of these young people. Shame for what they had done, shame for what happened to them, shame of physical appearance, shame for who they were.

In my clinical work with suicidal patients, I often heard that they did not know where to get help for an emotional crisis. They did not think that a doctor or a mental health service would be the right address to turn to. Or they were afraid of being sent to a psychiatric hospital against their will and “filled up with drugs.”

Tagging Suicide as a Form of Pathology Is Not Helpful

In emergency departments and psychiatric institutions, the prevalent model of suicide is still that suicide is the consequence of mental disorders or the result of various suicide risk factors. The inner experience of the suicidal person does not match with the health professional’s concept of suicide.

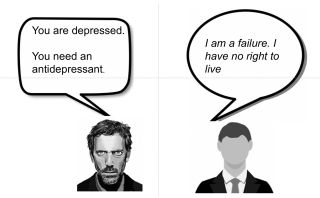

In my book (4), I used a graphic picture of Dr. House (from the TV show House) as an average physician in consultation with a suicidal patient to illustrate the problems of communication. Dr. House will not be able to relate to the patient because he is searching for signs of a mental disorder. This kind of interaction between the two protagonists has been called “dancing without touching.”

We need person-centered models of suicide that can provide a common ground for suicidal individuals and helpers to understand each other. This is the prerequisite to creating trust and personal insight in interacting with a health professional.

Understanding Suicidal Thoughts and How to Deal With Them

The first step is the appreciation of suicidal distress as a personal, understandable response to conflicts and adverse experiences. A recently published distress-processing model (5) offers a promising new approach based on the notion that people who are suicidal do not want to die but want to end their pain.

In our clinical work, we use a model of suicide as a personal action with an individual background. The key element is the notion that actions are explained with stories (“Well, this is a long story…”). I wrote about this model in my first Psychology Today post. The narrative approach, however, requires the professional helper to overcome the role of the expert who interprets a person’s suicidal behavior and knows what the person needs.

The new paradigm in clinical suicide prevention is that only the suicidal individual knows the personal story behind the suicidal thoughts and actions and that the helper is in the not-knowing position. If we want to encourage people to seek help, we need helpers who have the skills to listen and understand the suicidal person’s subjective experience empathically.

How to Reach People Who Do Not Seek Help

In the study mentioned earlier (2), I asked a group of people who all had a history of attempted suicide what could have saved them from harming themselves. Their answer was unanimous:

“We would have needed a person who would listen to us without trying to talk us out of it.”

This has been guiding me in my work with suicidal patients. A public health project that teaches helpers the skills to listen to people considering suicide empathically is Asist. Psychoeducational projects focusing on a crisis model have the potential to be meaningful to people and may reach individuals reluctant to seek help. Examples are projects such as Befrienders Worldwide, ZeroReasonsWhy, and Orygen.

To Conclude: A Brief Message to People Considering Suicide

Psychological stress and pain are normal feelings that we can overcome. However, they may create catastrophic thinking: “It will never stop; it will only get worse.” We all have, in the past, developed our own coping skills to deal with negative experiences.

However, when we run out of coping resources, we need professional help. Thinking that nobody will understand and keeping suicidal thoughts to ourselves makes things worse. Talking to a trusted person is the key to survival. Suicide is not a solution to a temporary problem.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7, dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

1. Renaud, J., Berlim, M. T., Séguin, M., McGirr, A., Tousignant, M., & Turecki, G. (2009). Recent and lifetime utilization of health care services by children and adolescent suicide victims: a case-control study. J Affect Disord, 117(3), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.004.

2. Michel, K., Valach, L., Waeber, V. (1994). Understanding deliberate self-harm: The patients' views. Crisis, 15(4): 172-8.

3. Törnblom, A.W., Werbart, A., & Rydelius, P. A. (2013). Shame behind the masks: the parents' perspective on their sons' suicide. Arch Suicide Res 17(3), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.805644.

4. Michel, K. The Suicidal Person. A New Look at a Human Phenomenon. Columbia University Press 2023.

5. Mickelson, J. M., Cox, D. W., Young, R. A., & Kealy, D. (2024). A Distress-Processing Model for Clients in Suicidal Crisis. Crisis, 45(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000907.