Friends

The Me of Being White

Does understanding of who I am change in time? (Part 2)

Updated March 7, 2024

My father proudly talked about our house cleaner to friends and family as if she ranked a title. Maidservant. Merriam was a competent woman, quick on her feet with innate talents and charm. She was small in body size with a sweet soprano voice and such proper language —Yes madam. Will that be all, madam? — highly unsuitable for our standing; more like a warm-up for gainful employment on Park Avenue.

I don’t recall my parents calling Merriam The Schvartza to her face. They probably didn’t. But my father couldn’t help being suspicious of her, though he couldn’t say what of. One absurd misgiving was about her right to have a Jewish name. Another was that she came from Harlem, a community district of Manhattan that was reputed by White impressions to be a rat-infested, crime-ridden ghetto, smelling of rotting garbage. And there was one clinching argument that touched off a transparent allegation of theft.

“I had two 10-dollar bills in my wallet,” my father announced with a grating accusatory shake of his head synchronized to the sounds of his spoken words. “I left my wallet in my dresser drawer yesterday and today there’s one bill missing from it.”

My mother claimed to have taken it, blindly defending Merriam as honest. Listening to my parents’ arguments was like listening to two people in advanced stages of dementia discuss a bit of Spinoza’s philosophy of human behavior, the inseparability of body and mind, and the belief that reason cannot defeat emotion.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about my parents’ impressions of African Americans. They were typical White impressions cast from simple feelings of being privileged to be a White person in America. They grew up during radio days when people of color were portrayed only as either nondescript voices or as mockeries of Black people. When TV came into our lives, the faces they saw were almost exclusively White, and everyone around us was subconsciously aware of the privilege of his or her whiteness.

We lived in a land of plenty with the values of friends and relatives that looked like us. Somehow we all knew that that culture favored the color of our skin, though we would not dream of saying such things aloud, even to ourselves. We certainly didn’t think aloud about the hidden influences of White supremacy.

“That's because,” W. Kamau Bell, wrote in an Op-Ed on CNN, “a big part of White supremacy is about raising White people to think that if the world doesn't make sense to them, that means there is something wrong with the world—and not something wrong with the lens they are looking through.” [1]

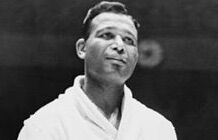

As far as I know, Merriam was just one of two persons of color my parents knew. The other was Mrs. Hurst who lived down the street. How was it that my father could be so severely suspicious of Merriam and not of Mrs. Hurst? That dichotomy never struck me as interesting in my early youth. I just assumed we—meaning everyone in my neighborhood—somehow placed Mrs. Hurst on a different level of blackness. She was, after all, the mother of Sugar Ray Robinson, middleweight boxing champion of the world, a person of rather significant worth.

Somehow, any connection to a celebrity of any color is an elevation of ego. There was, and still is, an inexplicable wannabe belief: Knowing a celebrity gives one bragging rights and the appearance of elevation to a mock-celebrity status.

As a kid, I didn’t know anything about my powers to rage against injustice. My White friends did not fully understand that Black people were free and equal. Between workouts at Harry Wiley’s gym on 135th Street in Manhattan and regular visits to his mother on West 238th Street in the Bronx, “Sugar” would shoot some hoops with us on the street. A basketball hoop was nailed to a plywood backboard on a telephone pole.

At first, when we didn’t know his fame, some kids stood on the sidelines with an eye of suspicion. I was the tallest kid on the block, about as tall as Robinson. Though tall, I was terrible at the sport. I had trouble with my aim—always have. But Robinson taught me to dance with the ball; he was so good at it his movements, some kids began to relax and join in. But some with implanted racist suspicions continued to watch with scorn.

Then came a time when we learned who he was. It changed everyone’s behavior. We all became quite thrilled with the thought of calling him “our basketball friend, Sugar.” We imitated his fancy footwork. We danced the tango. And when he went off to his fights, all the neighborhood kids ran through the streets alongside his fuchsia Cadillac convertible to wave him good luck.

The moment we found out that he was the middleweight boxing champion of the world, he became one of us, a celebrity that made us feel as though we too were celebrities of worth. Celebrities have no color because—I’m guessing with no evidence—yearnings of self-esteem through associations with fame can outplay racial prejudices.

References

1. W. Kamau Bell, “What every American needs to Know about White supremacy,” CNN, Sunday, July 19, 2020.

https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/19/opinions/united-shades-white-supremacy-k…