Burnout

Is It Possible to Feel Sympathy For Many People at Once?

Our feelings respond to images, not numbers.

Posted June 10, 2014

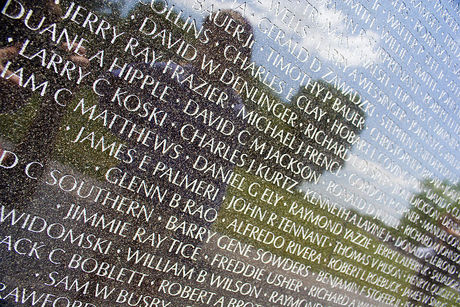

Detail of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Our imagination is used frequently in simple comprehension and understanding of what we are told. But we don’t always use it. We don’t always have to. Psychologist Elizabeth Dunn ran an experiment which showed people descriptions of tragedies and then measured how sad they were. What she found was interesting—and profound. Some people were told that 5 people had died in a Spanish forest fire, and others were told that 10,000 people had died in a forest fire. Even though people thought they would feel differently about these two situations, they didn't. People are insensitive to number in situations like this. They feel just as bad in either case.

Why would this be? Numbers, as symbols that are communicated, are very recent cultural inventions, compared to our evolutionary history. This means that the more primitive, evolutionarily older parts of our minds, which include the basic sensory and emotional parts, do not really understand them very well. What the older parts of the mind are better at understanding are things like images and narratives. Dunn made another version of the experiment that described either 15 or 500 soldiers dying. In one condition, participants saw photos of the dead. In the other, they just heard the number of dead soldiers. The pictures made a difference. Seeing 15 vs. 500 photos of dead people makes for a bigger difference than simply seeing the numbers 15 vs. 500.[1]

On the other hand, a study by Paul Slovic found that people were more upset by a tragic story about a single person than a tragic story about many. In fact, people would donate more money to a charity if the description was of one person than if it was of many people, or even it was of one person plus some statistics to show the scope of the problem.[2] It seems that people are slightly number sensitive, but in the wrong direction—they care more about one person more than two or more!

Why are they sensitive to number in Slovic's experiment but not in Dunn's first one?

Our compassion and sympathy is generated by the old brain, and the old brain simply doesn’t deal with numbers. It responds very well, though, to sensory stimuli, which is why Dunn got the results she did with the pictures. In Slovic's experiment, a rich text description was given of a person, which allowed the reader to make a clear, emotional image in his or her mind. It's hard to make an image that really captures the suffering of lots of people at once. As such, the newer brain takes over, and thinks of it, more coolly, as a number.

Although I have not seen a study do this, I think that even imagery cannot adequately communicate really large numbers of people. Think of the millions that died in Stalin’s Russia—one can try to turn this into a concrete image, looking at picture after picture, that eventually one’s mind becomes numb to it. Pictured is the Vietnam Veteran's Memorial, which has inscribed upon it over fifty-eight thousand names. No photograph can even capture all of the names at once. It is a bold attempt to capture the scope of American death, but would it be any less moving if there had only been twenty-five thousand names? As you look at the memorial, the names become a texture, and once again, you become insensitive to number.

Our minds are excellent detectors of change, but once a pattern is understood, the individual pieces that make up that pattern fade from consciousness. We get “burned out” when we hear about the same social issues again and again, and they fail to move us as they once did. So although imagination is better than statistics for making us feel compassion, the limited nature of sensory imagery, and its inability to really render the scope of huge problems, can leave us feeling flat.

Although people can understand that it's worse for two million people to die than one million, it seems there is no way to really make people feel it.

[1] Dunn, E. W., & Ashton-James, C. (2008). On emotional innumeracy: Predicted and actual affective responses to grand-scale tragedies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,44, 692-698.

[2] Slovic, P. (2007). ‘If I look at the mass I will never act’: Psychic numbing and genocide. Judgment and Decision Making, 2(2), 79-95.