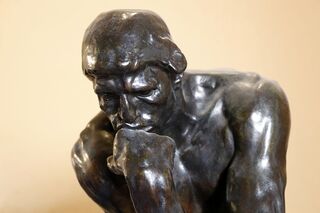

Wisdom

5 Nuggets of Ancient Wisdom We Rely on Today

How modern therapy is infused with ancient thought.

Posted February 23, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is infused with doses of Stoic wisdom.

- According to Stoic philosophy, the causes of our emotions lie within ourselves.

- Changing our dialogue with ourselves changes how we respond to life events.

Modern psychology owes a debt of gratitude to ancient philosophy, especially to the Greco-Roman school of philosophy called Stoicism. As a cognitive behavioral therapist, I know that many of the techniques and underlying principles I use in practice reflect these ancient teachings.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, the most widely practiced form of therapy today, helps people identify and correct the distorted, irrational, and exaggerated ways of thinking that underpin negative emotional states such as anxiety, depression, guilt, worry, and anger. In CBT, the therapist guides the patient to identify the thought triggers that lead to emotional distress and substitute more adaptive ways of thinking and relating to others. We help patients rethink their negative thoughts and question their deeper underlying beliefs (called core beliefs), which give rise to these disturbing thoughts.

My clinical work involves a blending of modern therapy and ancient wisdom, using techniques developed by cognitive behavioral therapists while drawing upon philosophical traditions, especially Stoicism. Here are a few choice nuggets, drawn from Stoic teachings, that offer bits of wisdom to live by:

1. Anything you possess is merely leased, never owned.

If you are lucky, you’ll have a long-term lease on health, wealth, and loving relationships. But life is finite, and we need to be prepared to return whatever we have whenever our chips are finally cashed in. After all, no one gets out of life alive. The Stoics teach that we should not become so attached to things that we could not bear to part with them—for part with them, we eventually must.

We may wish that our health and loved ones will be with us forever, but these things, like virtually all things, are not within our power to control. The founder of Stoicism, the early-third-century (BCE) Greek philosopher Zeno, explained that “happiness is a smoothly flowing life.” Happiness comes from how we live our lives, not from the stuff we acquire along the way.

We find happiness by cultivating our character and living each day fully and productively, not by counting the things we have acquired. Remember, too, that even shiny new objects quickly lose their luster. The Stoic sage Epictetus (circa 55-135 CE) wrote, “Never say of anything, ‘I have lost it,’ but, ‘I have restored it.’” Everything is returned once our lease on life expires, if not sooner.

Alas, the world and the wider universe take little, if any, note of our lives. We occupy space on this rotating orb for but a mere instant in the vast span of time. We live, we die, and we are soon forgotten.

Lest we get too pumped up with ourselves, the Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE) reminds us that we all eventually wind up in the same place. He pointed out that despite their very different stations in life, “Alexander the Great and his mule driver both died, and the same thing happened to both.” Rather than becoming demoralized by the impermanence of life and by our cosmic insignificance, we should take Stoic advice to find our place in the nature of things and make the most of the time we have been granted, for tomorrow never knows.

2. Want only what you can obtain; don’t want what you cannot have.

Pinning your happiness on things beyond your control eventually leads to unhappiness. We may want Jordan’s love and affection, or to fit into the clothes we wore in college, or to land that promotion at work, or to win the lottery, but wishing and hoping doesn’t make it so. It only makes you miserable if you want something that lies beyond your reach. Rather, scale your expectations to what you can reasonably achieve and avoid putting demands on yourself for things you cannot have. As the first-century (CE) Roman senator and Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote, “A wise man is content with his lot, whatever it may be, without wishing for what he has not.”

3. Control what you can and let go of the rest.

A central theme in Stoicism is the importance placed on recognizing what we can control and what we cannot. This theme resonates across the ages and is perhaps best known to us today in its modern form in the “Serenity Prayer” offered by the Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971):

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

Whether we express this Stoic belief in prayer, apply it as a philosophy of life, or bring it into the therapist’s consulting room, we can benefit from the wisdom of respecting the boundaries between things we can control and things we can’t. As Epictetus believed, it is foolish and futile to worry about things we cannot control. We may not be able to control things outside ourselves, but we can control our mental attitudes and how we react to our life experiences.

4. The causes of your emotions are within yourself.

There is no such thing as a “bad” event. Events just are. It’s how we judge them that makes them good or bad. Shakespeare put it succinctly in Hamlet when he wrote, “Nothing is either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

The Stoics taught that life experiences are not what make us happy or miserable, but rather, it’s our interpretation of events that makes the difference. This principle is foundational not only to Stoicism but to present-day cognitive behavioral therapy. Some two thousand years ago, Epictetus wrote, “Men are disturbed not by things, but by the views which they take of things.” Applying this dose of ancient wisdom, we recognize that it’s how we respond to things that causes emotional distress, not the things themselves.

Despite the common belief that Stoicism involves a “grin-and-bear-it” approach to life, Stoics did not believe we should be emotionless. Yet they advised that we should not allow our emotions to get out of hand. When upsetting things happen, it is reasonable to be upset, but turning disappointment into despair or annoyance into lingering anger or resentment is something we do to ourselves.

5. Don’t let others push your emotional buttons.

Epictetus and the other Stoics recognized a basic truth, that while we can’t control most things in life (would that we could), we can control how we respond to life events. What Carol did to you (insult you, reject you, disappoint you) or what Rick didn’t do (call you, text you, declare his love for you) may be disappointing, unfortunate, or annoying, but a million Carols or Ricks cannot make you feel anything, unless you allow them.

Your emotional reactions are internal mental experiences you control by how you respond to events and what you say to yourself under your breath. If Jack does or says hurtful things, recognize he is doing what Jack does. Don’t take it inside and make it yours. We get angry when we say anger-inducing things to ourselves and upset when we say upsetting things to ourselves. Change the dialogue with yourself, and you will change your emotional response.

As Eleanor Roosevelt said, “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” You can decide to withhold your consent whenever someone tries to turn your mind against you to make you feel inferior, stupid, lazy, useless, or inadequate.

Are there any tasty nuggets here for you to chew on?

(c) 2022 Jeffrey S. Nevid