Motivation

Beyond SMART: An Evidence-Based Formula for Goal Setting

SMART goals work well in the office but miss the human side of goal setting.

Posted October 24, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

One of the curious disparities among people reporting a desire for a better life is the small percentage who set actual goals to make their lives better.

This disparity is difficult to understand because goal setting is so well-established as a contributor to success by scientists and highly successful people. Entrepreneur Richard Branson, for example, summarized his perspective on goal setting as follows: "Setting goals is the first step from the invisible to the visible."

Goal setting has long been recommended for achieving better health, a larger income, and a more rewarding lifestyle—purposefully appearing as the very first lesson in Napoleon Hill’s masterpiece, Law of Success, in 1927 (he referred to a goal as a “definite chief aim.”) Nearly a century after Law of Success, the best goal setting research was combined into a “meta-analysis” published in 2011, with the results affirming the positive effect of goal setting on performance (1). If goal-setting is such a no-brainer for improving our results, why don’t more people set goals?

Among those seeking professional assistance for improving their health, goal setting is difficult to avoid. The teaching of goal-setting skills is now a bread and butter tool among health educators, healthcare providers, and self-help programs in many forms, to name a few. Whether to help people lose weight, stop smoking, or manage chronic diseases, nearly every established treatment program encourages goal-setting.

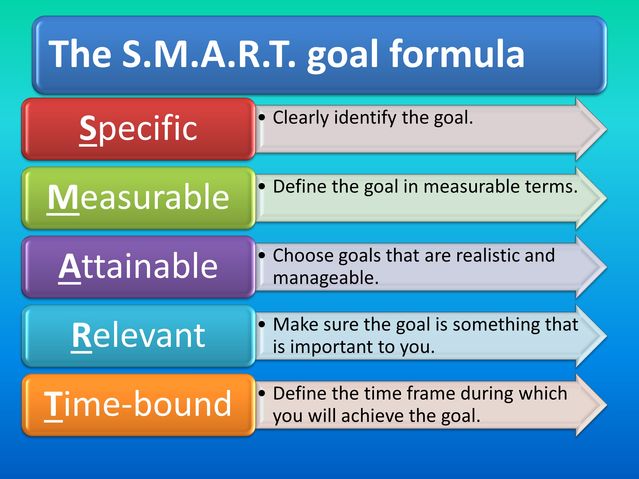

In these programs, goal setting is most commonly recommended using a formula called SMART (referring—with some variations—to Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely). Interestingly, the SMART goal concept originates from the business sector in the early 1980s, where it was initially introduced to managers as a more consistent formula for communicating business objectives. Catchy and easily remembered, however, SMART goals spread rapidly from the business sector to the health and self-help industries.

Unfortunately—but perhaps not surprisingly—the business-derived SMART goal formula seems to produce better results for office managers than for people striving to improve their health. Despite decades of use, for example, there is little or no scientific data that the overall SMART goal formula either increases goal-setting behavior (i.e., inspires more people to set goals) or produces better results than goal-setting without using the SMART formula.

On one hand, some writers have countered that components of the SMART goal formula could backfire, such as by reducing motivation from setting “realistic” instead of exciting goals. On the other hand, research shows that the SMART goal formula omits empirically supported goal setting strategies. In combination, the widely used SMART goal formula can be criticized both for including strategies that aren’t proven to work and for failing to include goal-setting strategies that are proven.

On the other hand, none of these criticisms are entirely fair to the SMART goal formula that, again, was designed to help managers write goals for soulless quarterly reports, not to inspire health transformations. Perhaps both the primary strength and the primary limitation of the SMART goal formula is that it is better suited to the practical goals of the workplace rather than goals such as health and lifestyle changes that are based as much on inspiration as information. If so, then simply being memorable won’t ever make the SMART formula an effective tool for helping people set and achieve health-related goals. What will?

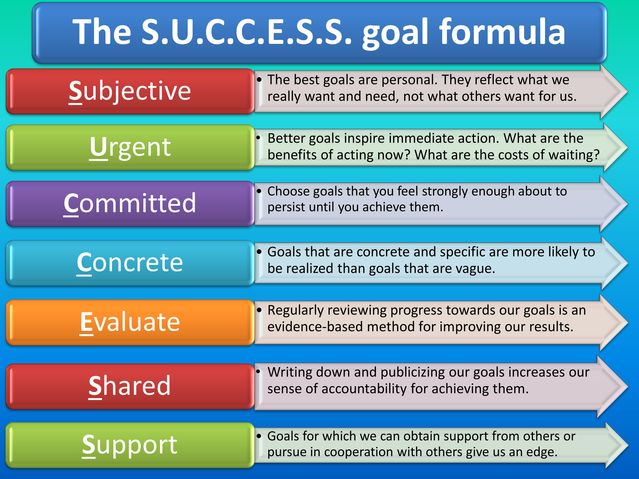

The figure below outlines an alternative goal-setting formula to SMART, called SUCCESS. The advantages of the SUCCESS goal formula are:

- Like SMART, it is easily remembered and promotes positive emotions about goal-setting.

- It includes the goal-setting strategies demonstrated through research and professional experience to be effective.

Applying the SUCCESS goal formula involves using as many of the seven dimensions as possible in formulating a goal but does not require that all of them be applied to any individual goal.

Goal setting formulas that haven't worked in the past are unlikely to work in the future. Whether you are a person hoping to use goals to improve your own health results or a professional helping others to achieve their health goals, consider a better formula to realize better results.

References

1. Kleingeld, A., van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289-1304.