Domestic Violence

A Memoir Opens a Literary Window onto Domestic Abuse

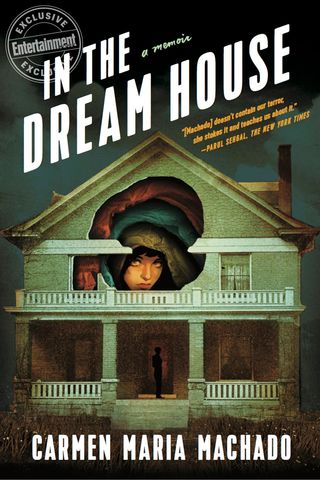

Carmen Maria Machado's In the Dreamhouse on LBGT domestic abuse

Posted November 11, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

"Don't you ever write about this," Carmen Maria Machado's girlfriend tells her, referring to an explosion of verbal abuse. The title of Machado's In the Dreamhouse is a metaphor for the intoxicating, dangerous relationship the book chronicles. To enter the dreamhouse is to confront difficult empathy.

Machado is forthright about her intent: "I enter into the archive that domestic abuse is both possible and common between partners who share a gender identity, and it can look something like this." The book's dedication page reads, "If you need this book, then it is for you." But this gothic, erotic, sometimes hilarious memoir belongs on the self-help shelf only in the sense that it subverts, upends, and reinvents the genre.

The world needs this book, an intensely literary story of a relationship between two writers, two ambitious women whose connection is fused by sexy devotion and sickening cruelty. And we need this book precisely because it's so literary—enabling a view of domestic abuse, in the LGBT community and beyond, that only literature can manifest. Machado invites empathy that entwines the particular, sensory, multi-faceted, contradictory, suspenseful, terrifying dimensions of her experience. Machado's canny move is to avoid overestimating empathy. She uses formal experimentation to extend it into moral and political territory.

In her 1985 landmark book The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry makes the point that it's difficult to share another's pain. To experience pain is to "have certainty" about how it feels, physically and emotionally. To read about or think about that pain is "to have doubt." We can't experience the certainty of somebody else's pain. Perhaps this is one reason so many people who experience abuse or assault struggle to get others to believe or understand what they've been through. Machado's literary experiment engages readers in the physical, psychological, emotional, and intellectual experience she chronicles. She avoids the pitfalls of sensationalism and voyeurism through a literary exploration that demands engagement with empathy in all its complexity.

Much of the book is narrated in the second person, Machado the narrator in the present addressing Machado the woman who endured the abuse. The technique creates both distance and intimacy. It's hard to imagine a policy statement or psychological study rendering the sensory moment when a person realizes she's being abused.

For example, this scene, when Machado is chatting with her girlfriend's mother:

Your girlfriend comes into the kitchen, and asks, "What are you reading?" as her hand starts to circle your arm. "I'm..." you start to reply, and her fingers tighten.

Her mother, still chopping, says, "Are you girls still going to the beach? Her knife raps against the cutting board with unnerving precision.

Her grip goes hard, begins to hurt. You don't understand; you don't understand so profoundly so your brain skitters, skips, backs up. You make a tiny gasp, the tiniest gasp you can. It is the first time she is touching you in a way that is not filled with love, and you don't know what to do. This is not normal, this is not normal, this is not normal. Your brain is scrambling for an explanation, and it hurts more and more, and everything is static. Your thoughts are accompanied by a ramp of alarm, and you are so focused on it that you miss her response.

The sensory image of that tightening grip is terrifying, constraining. While a reader can't feel its physicality, we follow as the sensory detail blends, as it would in life, with an emotional response—confusion, fear, embarrassment. As her brain skitters and scrambles, the emotional response blends with an intellectual one, the hope of an explanation: "This is not normal." When none comes, as the pain increases, "everything is static." Machado's disassociation keeps her from responding with anything other than the tiny gasp.

This is the moment when Machado trains herself, is trained, to protect her abuser and stick around, despite her considerable intellectual and ethical resistance to being victimized. Experts on domestic abuse commonly make the point that emotional and physical abuse are intimately connected. Machado breathes life into that observation, training readers to feel that intimate connection. She envelops us in the tumult of her psychology—the mixed feelings, uncertain motivations, doubts, secrets, and convictions.

In her book, Empathy and the Novel, Suzanne Keen outlines the subtleties and the limits of empathy. She surveys psychological research that shows that witnessing pain activates neural systems associated with affective dimensions of pain, but not direct, physical ones. She makes the point that it can be easier to empathize with fictional pain than actual pain. Empathy, she suggests, doesn't necessarily lead to "action." In his book Against Empathy, psychologist Paul Bloom argues that empathy alone won't "save the world." In his view, "empathy can be nurture, stanched, developed, and extended through the imagination." According to Bloom, "there is more to kindness and morality than empathy." Through her formal experiments, Machado invites readers to develop and extend their empathy into the kindness and morality Bloom envisions--and requires, if it is to become politically effective.

In another harrowing scene, Machado shows just how thin the line between emotional and physical abuse becomes as the relationship develops:

She leans over and screams directly in your ear, like she's pouring acid out of her mouth and into you. You try to scramble away, but she is pushing on your body, howling like a wounded bear, like an ancient god. (An ancient bear; a wounded god.)

It is as something has been cut loose. You roll off the couch, stand, and dart to the other side of the room. She vanishes into her bedroom and comes out again with your suitcase. With a tremendous yell, she hurls it across the room, where it crashes into the wall. She reaches down and grabs something—your very fancy ModCloth boot, the first pair of shoes you've ever spent that much money on—and throws it at you. It spins, misses. She throws the other one, and it also misses you but takes a frame picture off the wall, and later you will try to figure out if she never landed a throw because you were so quick to dodge them or because she couldn't aim for shit, but you will never come to any conclusion.

Machado locks herself in the bathroom, finally coaxed out by her girlfriend, who looks at her terrified, tear-covered face and asks, "What's wrong? Why do you look so upset?" She's a gaslighting expert, chilling in the erasure of her own violence. Gaslighting may be an essential component of abuse, but it takes many forms. The scene's physicality, and Machado's reflections on it, make you feel bodies and minds fighting it out in a singular room. The screams, the acid simile, the scrambling, pushing, the throwing of shoes belong to these two women. The humor wondering if "she couldn't aim for shit" is a defining feature of Machado's resilient voice. Gaslighting is not just a category of behavior. It's a core element of the unnamed girlfriend's personality.

Machado writes about her unique version of an experience many share, one that's rampant. No two abusive dynamics are quite the same. Machado divests the story of abuse of all-too-common generalities, conventions, or clichés. In her words:

Your brain can't engage a cliché, not properly—it skitters right over the phrase or sentence or idea without a second thought. To describe an abusive situation is almost certainly to deploy cliché: "If I can't have you, no on can." "Who will believe you?" "It was good then it was bad, then it was good again." "If I stayed, I would have died." Awful and dehumanizing, and yet straight out of central casting. This triteness, this predictability, has a flattening effect, making singularly boring what is in fact a defining and terrible experience.

If clichés flatten, Machado makes it her job to revivify her "defining and terrible experience." By experimenting with literary form, she brings us closer to the weird intimacies of the abusive dynamic she experienced.

Machado offers both kudos and gratitude to activists and academics who have written about "intimate partner violence" in the LGBT community. The research and writing, even if there is too little of it, is important and necessary. Advocacy groups like the NW Network and the Anti-Violence Project offer resources and protection for victims and survivors—working to destigmatize LGBT "intimate partner violence" even while they must work to create awareness that it even takes place. The Williams Institute and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) have published detailed reports summarizing the limited research on the topic.

Machado's book demonstrates that literary voices are just as important. Her book helps readers understand the intimacies that make domestic violence possible. In addition to portraying the subtleties of the psychology of one relationship, Machado tells a downright suspenseful story. The suspense is creepy because it compels readers to wonder how far the cruelty and violence will go. Machado is a master of creepy. Her collection of intricate gothic fiction, Her Body and Other Parties, was a finalist for a National Book Award. Her mastery prevents this creepy suspense from veering into exploitation or sensationalism, which she avoids through humor, self-reflection (and deprecation), pop culture references, and formal invention.

Machado's memoir is bursting with literary references and devices, examining love and violence by way of multiple genres. Machado titles her chapters "Dreamhouse as Confession," "Dreamhouse as Lesbian Cult Classic," "Dreamhouse as Checkhov's Trigger," "Dreamhouse as Pop Song," and so on. The literariness never feels simply clever. In fact, it can reveal bracing moments of wisdom.

A chapter entitled "Dreamhouse as Epiphany" is a single line: "Most types of domestic abuse are completely legal." Emotional manipulation is not illegal; gaslighting, not illegal. What about throwing a shoe and missing your target? Gripping your partner's arm with the deliberate intention to cause pain and humiliation? In a chapter about the 1944 movie Gaslight, featuring Ingrid Bergman's "iconic, disheveled performance," Machado concludes with the astute observation that "abusers do not need to be, and rarely are, cackling maniacs. They just need to want something and not care how they get it."

In other words, abusers—like victims—come with various motives. Machado's abuser is charismatic, a talented writer, a child of Florida, great in bed, with an interest in herb gardens and good food. Machado is wry, a talented writer, obsessed with Star Trek, and self-conscious about her body. She's defiant, publishing a full-length book in response to her abuser's warning: "Don't you ever write about this." Machado refuses easy narrative closure: "That there's an ending to anything is, I'm pretty sure, the lie of all autobiographical writing. You have to choose somewhere. You have to let the reader go."

Rather than ending on a climactic narrative note, Machado extends her story beyond herself. She concludes with an Afterword that works as an affectionate annotated bibliography of the small but growing literature on abuse in LGBT communities.