Ketamine

What to Know About Ketamine for Psychiatric Use

Its history and current use to treat depression and other disorders.

Updated April 26, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Ketamine, initially devised as a surgical anesthetic, is now gaining in popularity as a psychiatric drug.

- Different forms of ketamine exist, but only the nasal spray "Spravato" is FDA-approved for psychiatric use.

- Ketamine induces feelings of relaxation and dissociation that can assist psychotherapy in different ways.

This post is Part 1 of a series.

Ketamine is a surgical anesthetic and analgesic drug that was first synthesized in 1962 and gained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1970 (Scarepace, Baresi & Morley, 1988) but more recently has been gaining traction for psychiatric treatment. At present, ketamine is now seen as a go-to drug, under controlled conditions, for those with treatment-resistant forms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other psychological diagnoses.

Ketamine: A Brief History

Ketamine gained popularity during the Vietnam War for surgical use because of its safety profile, relative to phencyclidine (PCP); however, for various reasons, its use at high doses declined over time for surgical purposes (Carillo et al., 2022; Sachdeval et al., 2023). The years following the Vietnam War saw increasing reports—both published and unpublished—of ketamine being used off-label to treat numerous psychiatric conditions, especially depression (Dore et al., 2019).

Then, in the 1990s, dissatisfaction with existing antidepressants that modulate norepinephrine and serotonin (i.e., tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs) led researchers to explore drugs that affected glutamate—and specifically within the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor class—with ketamine being a prime focus (Berman et al., 2000). Though at the time the serotonin hypothesis of depression appeared to have considerable scientific support, decades later we'd learn that many of the studies validating this hypothesis (and SSRI use for depression) were either faulty or their treatment effects were misrepresented (Moncrief et al., 2023).

Though ketamine's exact mechanisms of action are not completely understood, as it has both direct and indirect effects involving multiple neurotransmitters and brain regions, it's believed that ketamine’s psychotropic effects come, in part, from its antagonism of NMDA glutamate receptors (Bahji et al., 2021) and subsequent suppression of glutamatergic input onto GABA-ergic interneurons. Interestingly, ketamine's novelty as an antidepressant isn't just because it works on different neurotransmitters than existing drugs; findings from animal studies suggest that ketamine’s psychological/psychotherapeutic benefits may be related to its potential for neuroplastic and neurogenic responses (Bahji et al., 2021), as well as synaptogenesis and synaptic potentiation (Abdallah et al., 2015; Drodz et al., 2022; Zanos et al., 2018).

Ketamine also has applications in veterinary medicine as both an anesthetic and analgesic; however, it's important to note that in addition to its medical uses, ketamine has a dark history as an illicit street drug (under the name "Special K") used for getting high.

Ketamine's Different Forms and Their Legal Status

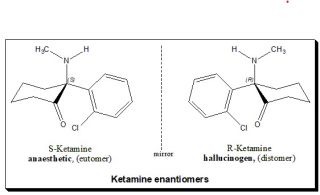

The original form of ketamine, formally known as "racemic" ketamine, is composed of two mirror-image molecules or enantiomers, known as S(+)-ketamine and R(–)-ketamine. S(+) and R(–) forms of ketamine can be isolated and compounded independently, and, theoretically, all three forms can be used pharmaceutically (Bahji et al., 2021; Scarepace, Baresi, & Morley, 1988), though typically only the racemic and S(+) forms are used.

At present, racemic ketamine is not FDA-approved for psychiatric treatment; however, it's been used off-label for decades for psychiatric treatment, and it's currently one of the two forms commonly used today in this capacity. However, in 2019, the S(+) form of ketamine (generic name "esketamine"; trade name “Spravato”) attained limited FDA approval as a nasal spray for adults with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), and then in 2020 approval was extended to those with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or behavior (Mischel & Balon, 2021). In both cases, approval limited use to the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) safety program. Under the REMS program, Spravato must be administered in certified, medically supervised health care settings where patients are closely monitored (Cottone, 2023).

Though esketamine/Spravato is offered exclusively as a nasal spray, racemic ketamine can be administered in several ways, including noninvasively through oral and nasal routes, as well as by injection (i.e., subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous), with each route of administration having advantages and disadvantages. In general, administration routes that are less invasive (e.g., oral and nasal) have lower bioavailability and absorption rates and, thus, require higher doses (with greater side effects) than injection routes (e.g., IV).

As noted above, ketamine dosing depends on which form (racemic vs. esketamine) and which administration route (e.g., oral, nasal, IV) is used. The esketamine/Spravato nasal spray, which at present is the only FDA-approved form of ketamine, is dispensed in spray bottles that have two sprays of the drug in each device, with each spray being 14 mg (and each bottle having 28 mg). Officially, Janssen (the manufacturer of Spravato) recommends dosages up to 84 mg (i.e., six sprays or three spray bottles); however, unofficially, I've worked with patients taking Spravato who have had off-label doses higher than this.

Racemic ketamine can be administered, off-label, in several forms. As a nasal spray, racemic ketamine is often compounded in bottles with higher volumes than Spravato bottles, where each spray is 10 mg, and typical doses are between 100 and 200 mg (i.e., 10 to 20 sprays). When administered intravenously, dosages (which are typically smaller than the nasal sprays) can be fine-tuned more easily to a patient’s optimal level, and it works faster than other routes (Tully et al., 2022). Fava and colleagues (2018) demonstrated that both standard IV doses (0.5 mg/kg) and high IV doses (1.0 mg/kg) are superior to placebo; however, interestingly, standard IV doses (0.5 mg/kg) showed greater and longer-lasting effects than high IV doses (1.0 mg/kg). To put these doses into context, a 200-pound man has a mass of 91 kg, and so a standard IV dose of 0.5 mg/kg equates to 45.5 mg while a high IV dose equates to 91 mg.

Oral forms of racemic ketamine (e.g., tablets, lozenges, and sublingual wafers) have lower bioavailability (20-25 percent) than intravenous (almost 100 percent) or intranasal esketamine (50 percent), and they're non-FDA-approved as well (Sobule & Ithman, 2023). Higher doses of oral ketamine (e.g., 150–250 mg, sublingually) are typically required due to their lower bioavailability, thus increasing the likelihood of adverse side effects.

What Does Ketamine Feel Like?

During an active treatment, which ranges from 30 to 90 minutes, individuals taking ketamine commonly report feeling relaxation, dissociation, being in a "trance-like state," relief of physical pain, floating, having an out-of-body experience, synesthesia, and subjective distortions of time (e.g., an hour feels like five minutes). On an anecdotal level, one patient recently told me that she often feels "the cord is cut" between her thoughts and her emotions during a ketamine session. Another patient frequently tells me that during each session he feels "the deck is cleared" in his mind of any psychological or emotional obstacles bringing him down or holding him back.

It's because of the emotional freedom referenced above that some of the best psychotherapy sessions may be possible when patients are having a ketamine session. Apropos of this, I recently published an account of one of the many impactful ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) sessions that I've had with my patients. During this session, ketamine allowed one of my patients to achieve significant separation between the memories of her past traumas and her emotional reactivity to them. As a result, she was able to consider ideas, perspectives, and interventions that, previously, her defense mechanisms would have rejected, and this spurred considerable progress in therapy in the weeks that followed (Cottone, 2023).

Depending on the dose, some patients can talk during a ketamine treatment while others can not. When doing a KAP with one of my patients and their psychiatrist, we often use a lower dosage so that they can communicate with me during their ketamine session.

Ketamine Side Effects

At the low doses of ketamine used for psychiatric treatment, most side effects are transient and usually resolve in an hour, with the most common being sleepiness, dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, and dry mouth. Other temporary, cardiovascular side effects include palpitations, elevated blood pressure, and increased heart rate, and, for this reason, ketamine treatment is often contraindicated for individuals with serious cardiovascular conditions. Furthermore, ketamine treatment is not recommended for anyone who has, or is at risk for, a psychotic disorder, as ketamine can induce psychotic-like symptoms in these individuals.

It's also possible that an individual having a ketamine treatment may experience a "bad trip," colloquially known as "falling into a k-hole." A k-hole is an acute, dissociative state that results from ketamine intoxication. It can sometimes be accompanied by physical immobilization, an inability to speak, and anxiety symptoms. K-hole experiences are more common when ketamine is used illicitly, outside of a medical context, but can sometimes occur during a formal treatment session. In my experience, k-holes are more common when an individual has not eaten all day before a session, is sleep-deprived, or is sick.

-----

In Part 2 of this series, a summary and case report of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is presented.

References

Abdallah, C.G., Sanacora, G., Duman, R.S., & Krystal, J.H. (2015). Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: A window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annual Review of Medicine 66(1), 509–523. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946

Bahji, A., Vazquez, G.H., Zarate Jr., C.A. (2021). Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278:542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.071

Berman R.M., Cappiello A., Anand A., Oren, D.A., Heninger, G.R., Charney, D.S., & Krystal, J.H. (2000). Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry. 47(4), 351–354. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9.

Carrillo, R. L., Garcia, K., Yalcin, N., Shah, M. (2022). Ketamine and its emergence in the field of neurology. Cureus 14(7). doi: 10.7759/cureus.27389

Cottone JG. Ketamine-Assisted Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2023 Dec;51(4):467–478. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2023.51.4.467. PMID: 38047669.

Dore, J., Tunipseed, B., Dwyer, S., Turnipseed, A., Andries, J., Ascani, G., Monnette, C., Huidekoper, A., Strauss, N. & Wolfson, P. (2019). Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP): Patient demographics, clinical data and outcomes in three large practices administering ketamine with psychotherapy. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51(2), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1587556

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry 28, 3243–3256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Mischel, N.A. & Balon, R. (2021). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021 May-Jun; 41(3): 233–235. Published online 2021 Apr 23. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001395

Sachdeva, B., Sachdeva, P., Ghosh, S., Ahmad, F., Sinha, J.K. (2023). Ketamine as a therapeutic agent in major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Potential medicinal and deleterious effects. Ibrain, 9(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibra.12094

Scarpace PJ, Baresi LA, Morley JE. (1988). Glucocorticoids modulate beta‐adrenoceptor subtypes and adenylate cyclase in brown fat. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism, 255(2):E153–E158. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1988.255.2.E153.

Sobule R, Ithman M. Ketamine: Studies Show Benefit. Mo Med. 2023 Jan-Feb;120(1):29–30. PMID: 36860608; PMCID: PMC9970333.

Tully, J. L., Dahlén, A. D., Haggarty, C. J., Schiöth, H. B., & Brooks, S. (2022). Ketamine treatment for refractory anxiety: A systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 88(10), 4412–4426.