Trauma

What Can an Index Card Teach You About Trauma Recovery?

Though the pain of trauma and loss never leaves, it can get smaller over time.

Updated November 16, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Everyone will experience trauma and loss at some point in their lives.

- Though the pain may never fully abate, it usually lessens over time and recedes into the background of life.

- The more a person focuses on being active and learning new things, the more quickly their pain will recede.

- The first 6 to 12 months after a trauma are crucial in helping a person move forward.

Trauma is an emotional reaction to an acute, negative event. Though the situations that can produce a trauma response are many, some of the most common include the death of a loved one, a serious accident, a sexual assault, a spousal affair, and even the loss of one's home in a fire. When a trauma happens to us personally, it's sometimes called a "direct trauma," but when we've witnessed it happen to someone else, it's called an "indirect trauma."

As a psychologist, much of my work involves helping people heal after exposure to traumatic events. At one point or another, we'll all experience pain caused by a traumatic event because no one escapes life without pain or the death of those important to us. In fact, according to psychoanalytic philosopher Ernest Becker (whose seminal work, The Denial of Death, won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize), nearly all human endeavors—science, religion, government, war, art, literature, etc.—are in some way defense mechanisms used distract ourselves from the traumas of death and loss.

"When will the pain go away?"

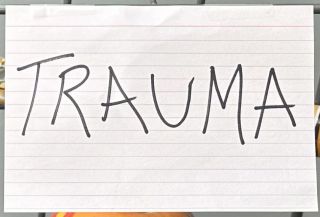

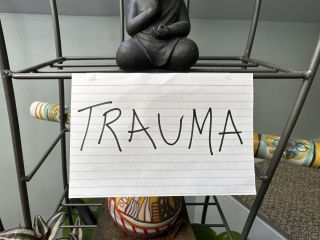

The question that I'm most often asked when working with someone who's experienced any kind of trauma or loss is: "When will the pain go away?" My response usually takes the form of a physical demonstration with the help of an index card (like in Figure 1 to the left). I start the demonstration by holding the card a few inches from a person's eyes so that it takes up nearly 100 percent of their field of vision, like Figure 1 to the left.

Then I'll ask a person to tell me about something current—a news story or something happening in their personal life—and for each new thing they tell me, I move back a few inches. After moving back a whole foot, the index card, though still large, now takes up only 50 percent of a person's field of vision (see Figure 2 below). Though the card hasn't gone away, other things around it start to capture the person's attention and curiosity.

Even though most people with whom I do this exercise struggle to focus on anything else but their trauma, at this part of the demonstration, they can acknowledge that there's more surrounding them than just the trauma: They just don't have much interest yet in any of those other things. In terms of time, this period represents the first three months following the trauma. It's an important time, but in my clinical experience, moving from this phase to the next phase is the most crucial period in one's recovery from trauma.

After getting more updates and moving back two more feet, the index card now comprises only about 10 percent of a person's field of vision (see Figure 3 below). For some people, this step back to the three-foot mark may be akin to how a person feels after two to three years have passed since the trauma; however, if a person has been considerably active, this level of progress can be achieved within 6 to 12 months following a trauma.

There are, of course, many other factors involved, including how direct an exposure one had to the trauma, whether physical pain or injury persists, and whether any important anniversaries or holidays are still on the horizon. However, all things being equal, in my clinical experience, I've found that the best way through trauma is to be as active as possible—especially outside the house—and to seek out as many new experiences as one can tolerate.

In some cases, circumstance requires that a patient remain busy for survival. At various points, I've worked with patients who've traumatically lost family members, but their employment and economic situations dictated that they work a regular schedule (or even add a second job) following a brief mourning period. Sometimes, external factors, like a tenuous financial situation requiring one to work more hours, can be a blessing in disguise, forcing a person out of the house (and usually around other people) for longer periods of time.

After getting several more updates and moving back 10 feet, the index card comprises only about 2 percent of a person's field of vision. Figure 4 shows an index card that is barely visible but still identifiable amidst the other objects, though a person must now go out of their way to look for it. So, it is with the pain of one's trauma at this stage, particularly if they've maintained a consistent activity level for several years.

In actual life, Figure 4 represents a stage of recovery from trauma in which a person may only be reminded of their respective trauma at selected times, like the event's anniversary (or if the trauma relates to another person, on that person's birthday), or if a person gets an unexpected, spontaneous reminder, like a picture memory on Facebook. Alternately, sometimes, a person feels guilty about "moving on" from having obsessive, intrusive thoughts about the trauma and will feel the need to seek out reminders, either to punish themselves paradoxically or for fear that they may totally forget it. In each case, these infrequent reminders still elicit pain, but usually not as much pain as they once did.

Recommendations

Below are some recommendations to help people push back their trauma index card to the furthest point possible in their mental visual field. In my experience, these recommendations shouldn't be implemented before the six-month mark, as the period immediately following a trauma usually demands that a person temporarily retreat to their comfort zone to let their wounds close. However, staying in one's comfort zone too long can lead to a "crust" forming around them, making it harder for them to not only leave their comfort zone but also transcend the trauma and its pain.

As such, the best time to start implementing some of these recommendations is between 6 and 12 months after the trauma.

- Start a new activity that doesn't have to do with recovery from the trauma.

- Start streaming a new TV series.

- Pursue volunteer work.

- Try a continuing education class in an area of interest at your local library or high school.

- Learn a new musical instrument.

- Join a meetup group around an activity that you're curious about.

With each of these recommendations, the main objective is to prevent a crust of isolation from forming by increasing social exposure, generating new brain connections, and creating more meaningful memories within the recent past to compete with the memories of the trauma and its aftermath.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. Simon and Schuster, NY.