Personal Perspectives

The Great Migration: White Fright and White Flight

Personal Perspective: Today’s mass migration brings to mind an earlier one.

Updated July 30, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I was thrilled when I saw the moving van across the street and the different sizes of bicycles being lifted off the truck. Since each bike meant a potential new friend, I was craning my neck to get a better look when I felt my mother yank my arm.

“You have plenty of friends already,” she said curtly as she gripped my hand and told me to come along now. Mom was not nearly as excited as I was about our new neighbors.

I was about seven years old at the time, with no way of knowing why some moving vans were more welcome than others. True, these newcomers had brown skin, like the family that had moved in two doors down the year before, but those two girls had become our playmates. New kids right across the street could only be another good thing. Right?

It wasn’t as if our Queens neighborhood was short on playmates. In fact, it was crawling with them. Some of the Irish families we knew had half a dozen kids or more – one family had 11! Maybe we didn’t need more friends, but of course, my sisters and I became buddies with our new neighbors. How could we not? Not only were we roughly the same ages as the new kids, but we shared the same last name. There we were, the Black Henrys and the White Henrys, in homes facing each other across our narrow street, one address number apart. We brought each other lots of mixed-up mail, played double Dutch and stickball in the street, and chalked hopscotch boards on each other’s sidewalks.

Our parents became friendly as well. Our dads sat together at the corner beer joint, and our moms chatted as they oversaw kids dashing back and forth between houses. It all seemed pretty normal, at least to us.

The Bigger Picture

What we didn’t know was that our parents were going to meetings in the evenings to discuss “the issue.” We did start hearing words like “blockbusting” when adults were talking, and we heard our parents saying things like “nobody has to sell” and “if everyone just stays put, we’ll be fine.”

Turns out our Irish, Italian, and German neighbors were upset about how many of the newcomers had brown skin. The first family on the block, well, okay. A second? A third, a fourth? That’s when the For Sale signs started going up.

My parents never understood that they had played a role in a dramatic social movement, never even heard of the Great Migration.

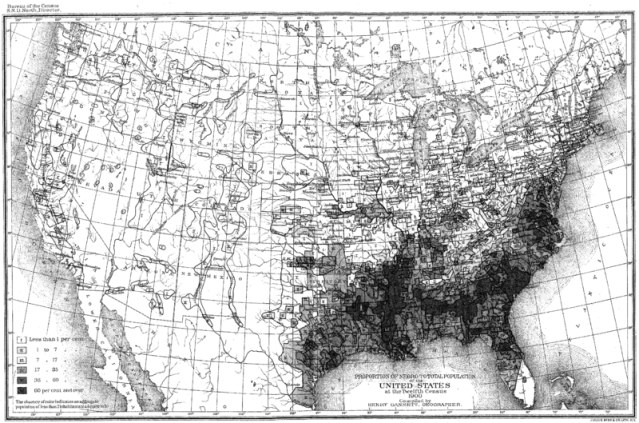

The words I didn’t hear at the time, or for many years afterward, were “Great Migration” or even “white flight.” Nobody talked about the massive population shift that was underway as American Blacks moved north to escape Jim Crow laws and in search of economic opportunity. There was no recognition that we were a part of something much larger than our block – at home I heard that nefarious real estate agents had targeted us and that the new families were ruining our neighborhood and would drive us out – just as “they” had driven my parents out of the South Bronx a decade earlier. The words I heard at home describing our new neighbors were not nice, despite the continuing friendship between the Black Henrys and the White Henrys. (There were, apparently, “some good ones.”)

Sounds Familiar

The words we hear today – about an invasion at our border and the criminals surging in to pollute our blood – are reminiscent of the conversations I heard back then. And just as the fear then focused on our block without considering the continental shift going on, the fear today ignores the global phenomenon of a massive international movement of people.

The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) monitors patterns of international migration, and the numbers are eye-popping. In 2020, more than 280 million people lived in a country other than the one in which they were born. That’s more than double the number in 1990 – an average of 4.27 million people a year for the past 30 years leaving their homelands. The 2020 number is more than three times the 1970 number.

People move for all kinds of reasons, of course – cultural, educational, economic, and political – and these numbers include all kinds of international migrants. But couple those numbers with a few others, and a pattern emerges.

Food scarcity: According to the World Food Program, 282 million people in 59 countries went hungry last year, more than double the previous year’s number.

Fear: Drug wars, gang violence, and politically motivated kidnappings and homicides are driving people away from their homes in record numbers. According to the IOM, some 90 percent of Mexican migrants in a 2022 report cited violence, extortion, armed clashes, or organized crime as their reasons for fleeing.

Is it so hard to understand why people whose children are hungry, or who live in daily fear of violence, would look for a way out?

When we focus our attention on the one hotel in the neighborhood sheltering migrants, we miss the larger picture of what’s gone so terribly wrong in so many other nations. When we listen to reports of an invading horde, we may not be mindful of the very human tragedies that are driving so many people to flee their homes. Ignoring today’s global pattern is as short-sighted now as ignoring the Great Migration was 50 years ago.

White Flight

My neighborhood reached some kind of tipping point around 1970, and my parents started to waver in their commitment to staying put. Real or imagined, the danger to white families became an ongoing topic of conversation; some neighbors added bars to their windows, and parents started to worry about letting formerly free-range kids go out on their own. By 1971, my parents had decided it was time to go, and in early 1972 we became part of white flight, leaving “the city” for “the suburbs.”

It was quite a while before I realized we had moved just seven miles – that’s how different the worlds were. Our new block had only white neighbors, and I heard my mother say that, of course, she could never invite her old pal to visit here. What would our new neighbors think if she brought a Black friend to the block? The friendship between the Black Henrys and the White Henrys was done.

My parents never understood that they had played a role in a dramatic social movement, never even heard of the Great Migration. They saw themselves as victims of greedy real estate agents and frightening invaders, not a part of one of the largest movements of people in American history. I don’t even know if it would have mattered. In the 1960s, it was a given that families that didn’t share a skin color didn’t share neighborhoods, either.

I would like to believe that we’ve learned a little something since then, that we could not just accept diversity but embrace it. A little human kindness about the reasons so many people are fleeing their homelands wouldn’t hurt, either.

References

World Migration Report (International Organization for Migration)

The Great Migration (National Archives)